Fiction

as a Medium of Social Communication

in 19th Century France

Sabina

Pstrocki-Sehovic

Abstract

This

article will present the extent to which literature could be viewed as

means of

social communication – i.e. informing and influencing society

– in 19thcentury

France, by analysing the appearance of three authors at different

points: the beginning, the middle

and the end of

the century. The first is the case of Balzac at

the

beginning of the 19th Century who becomes the most

successful

novelist of the century in France and who, in his prolific expression

and rich

vocabulary, portrays society from various angles in a huge opus of

almost 100

works, 93 of them making his Comédie humaine. The second is the

case of Gustave

Flaubert whose famous novel Madame

Bovary, which depicts a female character in a realist but also

in a

psychologically conscious manner, around the mid-19th

century

reaches French courts together with Les

Fleurs du Mal by Charles Baudelaire and is exposed as being

socially

judged for its alleged immorality. The last is the political affair of

Dreyfus

and its defender Emile Zola, the father of naturalism. This case

confirms the establishment

of more intense relations between writer and politics and builds a

solid way

for a more conscious and everyday political engagement in the literary

world

from the end of the 19th century onwards. These three are

the most

important cases which illustrate how fiction functioned in relation to

society,

state and readership in 19th century France.

Keywords:

social

communication; textual communication; books on

trials; censorship; 19th century France; Dreyfus affair; the

novel; interactions

between literary world and society

Introduction[1]

The need to communicate in

society has existed ever

since the emergence of humanity. It is often claimed that for

communication to

be successful, it must be informative. Therefore, communication must

indicate

an intended direction of thought or action. The readership of 18th

and 19th century shows sensibility for informative reading,

but also

for improving, entertaining and easy reading and this is why readers of

the

time searched for the new and most appropriate fictional form to

respond to

their needs.

Communication can also be

subtle, which means that

it can more or less conceal its intentions and its instrumental goals.

Written

or textual communication – which is in the focus of this analysis

– is

posterior to oral, which is from time-to-time transformed into written

communication, a process encouraged by the noticeable emergence of

literacy in

the general public. Oral communication was also more straightforward

than

written communication, but with the development of print, the process

of

communicating became more complex as exposure to written communication

increased.

Several definitions refer

to social communication as

a language used in social situations with the aim of establishing

mutual

understanding, informing or influencing society as a whole.[2]

Here we will analyse one particular literary genre, the novel, as a

powerful

tool of social communication in 19th century France. This

article

will briefly mention (i) what were the other most popular genres and

why, (ii)

what kind of language the authors used to represent their fictional

worlds,

(iii) what was the social surrounding and the atmosphere in which this

reception by the public happened, (iv) what problems the authors

experienced

with the state authorities and (v) how they developed their

communicative

relationship with the readers.

19th

Century France

The social and intellectual

life of

nineteenth-century France was marked by abrupt social, historical and

political

changes that gave social communication an increasing importance. In

1799, Napoleon Bonaparte was proclaimed emperor with unlimited power.

After

1815, the reign of the Bourbons was re-established and Louis XVIII

became King.

The country was struck by two revolutions in the first half of the

century: one

in July 1830, and the other in February 1848. With the Second Republic,

new

demands were made for both liberal and democratic reforms. The

organised

working-class emerged. The dictatorship regime of the Second Empire

followed,

and its power gradually weakened in the 1860s. In 1871, after

proclaiming of

the Third Republic, France returned to the values and objectives of the

famous

French Revolution from 1789, which created a new political rhetoric and

developed new symbolic forms of political practice (Hunt 1986).

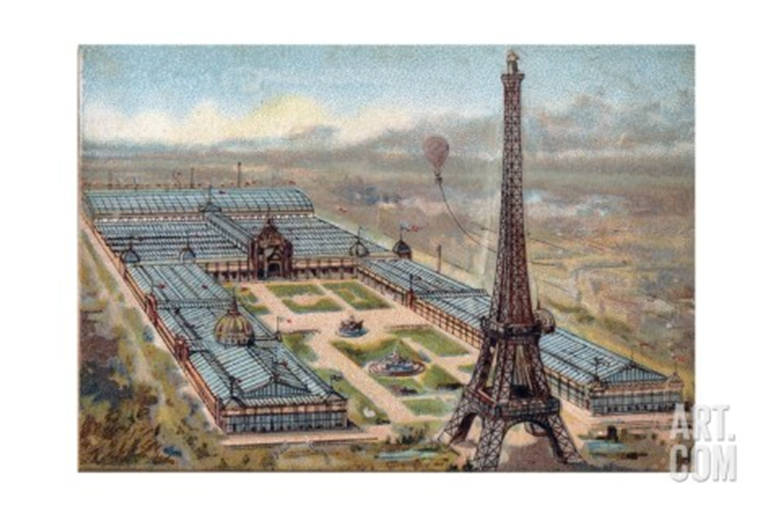

Exposition Universelle, the most

important cultural event in 19th century France took place

in Paris

exactly one hundred years after The Revolution. In front of the Tour

Eiffel,

villages from all over the country were presented, in order to

illustrate the

international character of la capitale. Visitors came from the

whole

world. Paris was `un lieu national`, a meaningless cosmopolitan

mix `faite

de toutes les races et de tous les pays` [made of all the races and

all the

countries][3].

Fiction was widely

influenced by this monumental commemoration, which glorified

technological

progress, capitalist expansion[4],

and provoked, in a way, the

imperial reign. Le Tour Eiffel was a symbol of the `concord of

nations`

(Prendergrast 1992: 8) and `prophetic vision of a future European

nation-state

of which Paris… would be the crowning glory` (ibid.:

15).

Universal Exposition of 1889

In literature of the 19th

century, we can

notice two different kinds of images of the city that were dominant. On

one

side, there was the Republican image, with its shared sense of

belonging and

purpose, and on the other side, the Imperial. This division in the

image of the

city was followed by political divisions, such as, for example, the one

created

between republicans and royalists by the Dreyfus affair. This helped to

establish the term ‘intellectual’,

which denotes the conscious citizen who criticizes the actual

happenings on the

political scene, eventually shares his opinions more or less

knowledgably with

his fellow citizens, and pronounces or at least holds political or

social views

about various actualities. The republican ideal was widespread and

authors like

Victor Hugo, who went into exile and had a personal hatred for Napoleon

III,

portrayed the `city as the focus of a unifying political culture

consisting of

free and equal citizens` (Prendergast 1992: 7).

However, in these times of

political unrest, the

city became more divided and started to reflect, perhaps more directly,

the

social status and the accompanying political affiliation of its

citizens. There

was the obvious gap between eastern rich quarters of Paris and its

western poor

areas inhabited by working and lower classes. Revolution gave more

importance

to the marginal citizens who had tendency to act differently, if

compared to

those at or near the centre. This marginal and peripheral outsider

created

psychological consequences for society and emerged as a new character

in

fiction after the French Revolution.[5]

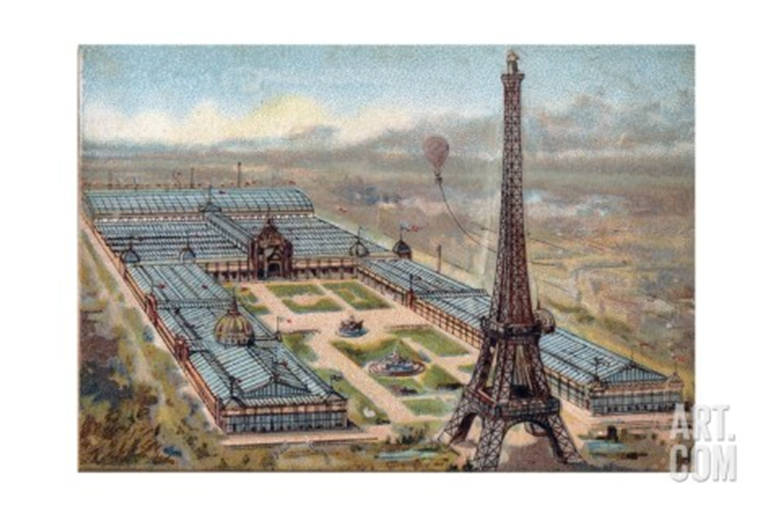

Parisian house 1845

Whereas the republican city

was the `expression of a

high degree of homogeneity`, parks and markets were the places of

divisions,

social hierarchy and class conflict (Prendergast 1992: 8). Parts of the

new

infrastructure were the typical French apartment houses. They

`undressed

the bourgeois family and exposed its dirty laundry to view` (Sharon

1999: 165)

and consequently `life threatened to become public` (ibid.

: 139). Generally, in such houses and mansions private

reading was difficult; there was little privacy and housing was

overcrowded.

Candles were considered a luxury, which meant scarcity of light for

reading.

Still, the novel primarily portrayed this private and domestic life.

Balzac

and the Rise of the Novel

The greatest change of the

period was the rise of

the novel, and it happened `after the French Revolution placed the

middle-class

in a position of social and literary power which their English

counterparts had

achieved, exactly a century before` (Watt 1957: 301). Its emergence was

related

to certain social phenomena: the development of the printing press and

journalism; the increase of the reading public ― especially in terms of

female

readers ; and the laws of censorship imposed by either state or church

in order

to keep stable political and religious order. The works of Honore de

Balzac,

the most important writer of the beginning of the 19th century,

can

demonstrate the impact of this literary genre on society and its

function in

social communication.

The works of Balzac

illustrate French society from

all angles and are capable of dealing with the totality of life,

presenting

stories which captured some of the moral values of the century.

Balzac’s works

demonstrate the strong connection between distinctive literary

qualities of the

novel and those of society in which it began to flourish. The rise of

the novel

meant the break with the tradition of old-fashioned romances, taking

inspiration instead from real-world characters and events. Therefore,

Balzac`s

opus of approximately one hundred books could be considered one of the

most

truthful portrayals of the society in the first half of the 19th

century.

Balzac’s characters represented a great variety of human

experience, including

all kinds of nomads, thieves, vagabonds, fornicators and

prostitutes,

working or unemployed, beggars or sometimes criminals who inhabited

Paris. We

could draw an interesting parallel between the particular choice of

characters

in Balzac’s with those in Charles Dickens’ novels in

England. Sharon (1999)

quotes figures of bachelors like Rastignac in Balzac’s Comédie

Humaine and

the omniscient portière, who sometimes becomes

identified with the

narrator. The setting of his novels in prisons, hospitals, slums,

brothels, all

make or reflect the social and psychic identity at the time as

uncertain and

problematic[6]

Newly conquered worlds are

often mentioned in books

published during the 19th century. Either the characters

travel,

like Nana to Egypt, or the authors themselves, like Flaubert in his Sentimental

Journey. Opening towards new worlds and cultures is characteristic

for many

states since the 18th century, the era of Enlightenment, not

just

for France or England, and confirmed by the fact that foreign fiction

was being

translated in French and English, and by the reverse process, or the

fact that

the authors wrote in foreign languages during and after their travels.

In

addition, English and French texts were being translated into other

foreign

languages.

During this period,

advertisements, dedications or

prefaces, giving additional explanations and sometimes warnings were

included

in the publication of such novels. The opening of a text is a critical

moment

both for the author and for the reader who share social and moral

experience through

the text. The foreword or preface sometimes provided information about

the

destinies of real people or revealed the true story behind the work.

The last

attempt of the author to monitor the reading of his work or to give his

own

views about the text can be contained in the postscript or postface,

which also

became a common addition for some books of the period. For example, in

the

preface to Comédie Humaine, Balzac speaks of

`sens-caché` [hidden

meaning] of the modern world. Author and reader could be considered as

two

strangers communicating through a printed book and in this way, a book

becomes

a medium of social communication, which also involves the transition

between

oral world of daily life and the written world of the book.

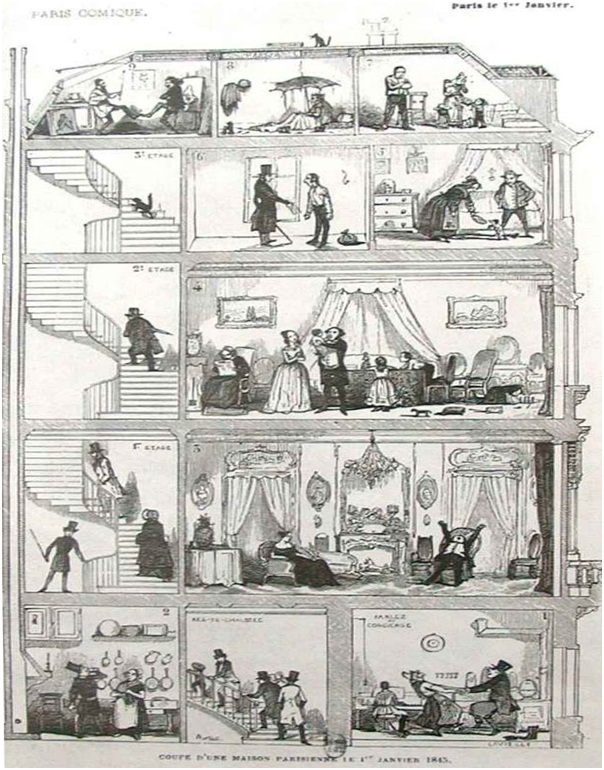

In terms of style and

language, like other French

realists, Balzac insisted on an almost scientific scrutiny of life,

true

correspondence and imitation of the `real`. History was present in his

text,

syntax and vocabulary. With active engagement in the text, pages were

transformed

into paysages. The diversity of social speech, later crowned in

Zola`s

dialogues of the working-class, was contributing to verity of the

fictional

discourse. The authors tended to believe that: `He who masters the

languages of

the city rules the city` (Prendergast 1992: 4 and 23).

Page from one of Balzac`s

works with handwritten

corrections

Intellectual claims in

philosophy of this period

included the view that an individual can discover the truth only

through his

senses (e.g. Locke and Reid), which had great influence on the novel.

In

addition, the novel is `distinguished from other genres by the amount

of

attention it habitually accords both to the individualisation of its

characters

and to the detailed presentation of their environment’ (Watt

1957: 18). The

plot of the 19th century novel in France was the complete opposite of

the

classical and renaissance epic, based on history, myth or fable. In

order to be

authentic the realist writer used poor formal conventions of

description in

detail and `the function of language was much more referential than in

other

literary forms` (ibid.: 230). For

example, Balzac’s Père Goriot

contains pages of descriptions

minutieuses [detailed

descriptions] of furniture, clothes, houses and city’s

sites. Its

blurred contours, together with the social preference for festivity and

fashion

were presented in the paintings of Édouard Manet and other

impressionists. The

role of language was the social constitution of reality, and the

preoccupation

of Balzac was the ephemeral and contemporary `outside’.

Balzac’s linguistics

was characterized by the `ornate`. Figurative language became much

rarer and

linguistic ‘ornate’ became very common. In France, critics

recognized the

elegance and concision in writers’ expression. The novel was

regarded as most

translatable because it was the most referential and it required less

historical and literary commentary. The formal realism of Balzac can be

regarded as a recognizable realist narrative method par

excellence.

The novel was a fresh genre

in character and style,

and there was the complete subordination of the text to the patterns

perceived

immediately. Sometimes the characters were named exactly in the same

way as

particular individuals in ordinary life and they were verbal

expressions of

identity both in society and in the novel. In contrast, classical

renaissance

literature favoured historical or type names and Molière`s

theatre favoured

social representatives with characteristic names and surnames like Tartuffe,

Le Bourgeois Gentil homme or Malade Immaginaire. Rablais

started the

practice of giving his characters names that denoted particular

qualities and

some later fictional characters could have also been related with one

particular and the most prominent trait of character, Moll

Flanders thief, Pamela

hypocrite, Tom Jones fornicator (Watt

1957). This change of character can be traced as replacement of the

knight-errant hero by a fine gentleman (Day 1987). Particularisation

and naming

of the character constitute verbal expressions of a particular identity

in

social life and in the novel.

Character also acts as the

bearer of social

communication between the reader and the author. There is no such

wealth of

detail accumulated in text or such abundance of minor references as in

Balzac’s

work. His sketchy portraits and the way he handles the text give full

portrayal

of the characters of his society. ‘The novel is distinguished

from other genres

by the amount of attention it habitually accords both to the

individualisation

of its characters and to the detailed presentation of their

environment’ (Watt

1957: 18). In his typical characterisation, Balzac was famous for

melancholy

attributed to his fictional characters and by physiognomy or the

aptitude of

recognising people by their physical appearance. He owed as much to

observation

as to imagination. In several novels there are personnages

reparaissants [reappearing characters], sometimes a bit

altered and the editions with illustrations were often suggestive about

the

outer looks of these ‘society-representatives’ and with the

illustrations they

could be better comprehended. These illustrations functioned in the

same way as

frontispieces accompanying numerous

editions of books in 19th century, and particularly some

collections

of fairy-tales. They were often there with the primary intention to

influence

the imagination of the reader. It was sometimes the author’s

pleasure to make

and write the additional eulogium,

therefore further influencing the reader. Fictional plot of the novel

had some

of the features of detective story, one of the most typical urban

genre.

However, the virtues of citizenship were not really exercised by the

characters

in novels of the early nineteenth century. Their inner world as well as

their

revelations stay mainly metaphysical in nature.

Whereas in Renaissance

literature, shaping of man’s

individual history was the expression of the collective history, and

timeless

stories were used to mirror unchanging moral verities, in the novel,

the temporal

dimension of human life was denied and the `space of a day` replaced by

the

`space of a lifetime`. Balzac, together with Stendhal was the first

great

efflorescence of the novelistic genre. For example, in the beginning of

Le

Père Goriot, Paris presents for a hero an opaque city with

no readability

or possibility of interpretation. `Paris est un

océan. Jetez-y

la sonde, vous n`en connaîtrez jamais la profondeur` [Paris

is an ocean. Even

if you

throw the anchor, you will never find out the depth] (Prendergast 1992:

110).

In his essay `Paris en 1831`, Balzac called it `la capitale

du monde,

sans égal dans l`univérs` [the capital of the world

without equal in the

universe]. The revelation of nature of the city as complex, intractable

and

impossible to master comes in the decisive moment of the funeral of

Le Père

Goriot, when the main character grasps and conquers for a moment

the

seditious and secret world of the city. Eugène Rastignac

conflates his sexual

success with urban when he cries ‘A nous deux’ [For the two

of us] to the one

he was in love with. Heroes in many novels tend to use a woman to gain

a

foothold of the city (Sharon 1999: 171).

Mid-19th

Century and the Trial of Madame Bovary

`In 1812, the first

cylinder press was invented: it

was considerably improved in the following years and could print 4000

to 5000

copies an hour by 1827` (Couturier 1991: 147). Paper became a great

deal

cheaper and censorship legislation was developed. Authors lived close

to, or

even with their publishers, but quarrels were not rare. In 1830s, Société

des gens de lettres was founded and aimed to secure better terms

for the

profession. A printer and bookseller needed the protection from those

who tried

to reissue a book or make fraudulent copies of it. The

known fact is

that the book-trade started to be run in a businesslike manner only in

the 19th

century, not before. ‘The novel was widely regarded as a typical

example of the

debased kind of writing by which the booksellers pandered to the

reading

public. The booksellers brought literature to the control by market

place and

they could as well encourage the author’ (Watt 1957: 54).

Complicity between the

Crown and the Church was much

greater in France than in England. The novel therefore developed in

England

with ease compared with France because of this absence of the legal

instruments

and allegedly more spirit of tolerance. On the eve of revolution,

following Code

Michaux, there were 178 censors and `Bastille often hosted the

authors, the

booksellers, or simply the carriers of banned books` (Lough 1978: 297).

Another

function invented for better control was the surveyor, and this regime

had

‘appalling effects on printing profession and reduced the number

of printers at

work in London from sixty to twenty’ (Couturier: 26). The

Catholic Church

censored and listed novels with `bad influence` in its Index

Librorum

Prohibitorum. One of the novels listed, for example, in the 18th

century was Pamela, a novel by Samuel

Richardson, which was thought to be a bad influence on the

‘weaker’ sex.

Although the other books like Michel Millot’s L’école

des filles, Nicholas Chorier’s L’Académie

des dames and Jean Barrin’s Venus dans le

cloître[7]

ran into difficulties, they continued to circulate and to reach their

readership.

In France, the law was less

tolerant and religious

struggles were bitter. However, and although it seems contradictory,

some

critics claim that French writers had greater freedom of expression

than their

English counterparts. In England, permission to allow a written work of

art was

needed from the Chancellor, but for a long time nothing was done to

define

literary property. Only one century earlier, those who wrote religious

literature could be sentenced to death. Law was not only meant `to

prevent the

publication of seditious books … but also that of obscene

literature in

general’(Couturier 1991: 26). It required that books should

contain nothing

‘contrary to good life or good manners’, a phrase which

seems to echo the

French description of obscene literature as contraire aux bonnes

moeurs [contrary

to the good manners] (ibid.).

According to some critics, this genre contributed to what could be

called the

degeneration of the century by questioning the established morals of

society.

For instance, Couturier mentions the novel as also subversive.

Censorship

developed on a grand scale since the 17th century. The above

mentioned Code Michaux of 1629 made

it compulsory to submit all manuscripts to censors appointed by the

Chancellors. The problem with Code

Michaux was that the printer or the bookseller usually did not

bother to

ask the author’s permission to publish a book, once he had the

permission from

the Chancellor.

The 18th century

was characterised by the

difficult relationship between the law and the book trade and the

French

language was subjected to very strict regulations and censorships.

Author’s

rights were recognised much earlier in England which explains why the

novel

bloomed half a century earlier in England than in France. However,

French

authors `had more power and influence socially than the authors on the

other

side of the Channel` (Couturier 1991).

After the Revolution,

freedom of expression was

officially recognized in article 11 of the Déclaration des

droits de l`homme

[Declaration of human rights], but printing wasn`t run in a

businesslike

manner until the very middle of the 19th century. Du Camp,

who

bought Madame Bovary for 2000 francs to publish it in his Revue

de

Paris in 1856, asked Flaubert to remove some passages because they

were

perceived as immoral or dangerous. Flaubert refused and sold the rights

to

Michel Lévy, who decided to publish the book complete. The case

finally reached

Tribunal Correctionnel, where

Flaubert appeared in court alongside Baudelaire on the same charge of

immorality for his Fleurs du Mal: `Flaubert

was acquitted, though the court offered some criticism of the morality

of Madame

Bovary, but Baudelaire was found guilty, fined 300 francs with

costs, and

ordered to remove six poems from subsequent editions of Les Fleurs

du Mal’ (Lough 1978: 285). Baudelaire`s

aggressive stance contained all kinds of provocative images and it

conveyed

emphasis on modernité, both social and artistic.

A couple of controversial

erotic scenes that were

skilfully painted and made lascivious by deliberate use of expressive

language

in Madame Bovary were discussed in the trial. It stated that

what the

author exhibited was the very poetry of adultery (Couturier 1991). `The

frivolous pages of Madame Bovary could fall into the more frivolous

hands of

girls, and even of married women sometimes and they could be induced to

follow

Emma`s example. It was a matter of public health and safety to ban the

book.

The attorney of the defence insisted that although the reader might

have felt

that Flaubert was on Emma`s side, the book also showed how she suffered

for her

sins and instructed young girls to be good and pure. The novel of the

time was

expected to have the `double mission of amusing and teaching’

(Iknayan 1961:

85). Flaubert scored immediate success with Madame Bovary, `partly

because of the publicity given to the book by prosecution ... none of

his later

novels had the same sales` (Lough 1978: 359).

Writers couldn`t control

the flow of the information

generated, once the book was published. Ever since, the difficulties

with

publishing sexually explicit fiction appeared, many books, although

they were

banned, continued to circulate. Perhaps this book by Flaubert looks

didactic,

when compared to the obscenity of The Crimes of Love, written

by Marquis

de Sade and published in 1800. His erotic ten-volume books like La

Nouvelle

Justine or Histoire Secrète d’Isabelle had

additional political

connotations. Although Flaubert only just escaped the death penalty and

spent

most of his life exiled in mental hospitals and prisons, he continued

to look

for assistance, in order to have his works published. `La

littérature est

l`expression de la société` [Literature is the expression

of society] writes

Bonald, about the fiction of this period (Iknayan 1961: 35). Madame

Bovary

was peinture des moeurs [painting of the customs] of the time

and though

the trial may seem absurd to some contemporaries, it stays exemplary in

many

respects (Iknayan 1961: 20).

Gradually, as writers

started to earn more,

patronage became another great source of income. The popular interest

in

reading increased and several factors affected the composition of the

book or

newspaper-buying public. ` The Education Act of 1870 in England and the

Lois

Jules Ferry of 1880-1 in France did not immediately change the

structure of the

book market, but they substantially increased the potential audience of

all

books, and of novels in particular` (Couturier 1991: 147). `Being able

to read

was a necessary accomplishment … for those destined to the

middle-class

occupations` (Watt 1957: 39-40), whereas

in Shakespearean England one needed a penny to stand in the Globe, `the

price

of a novel… would feed a family for a week or two` (ibid.:42).

There were still literary forms available for small

amounts of money: ballads, new stories of criminals, accounts of

extraordinary

events and pamphlets. Newspapers stayed quite cheap until taxation was

imposed.

Women, especially from the

upper and the middle class,

presented a large portion of the reading public. The main character of

Flaubert`s masterpiece was reading Balzac so enthusiastically that

‘she even

brings the novels to the dining table` (Prendergast 1992: 1). However,

as their

virtue could suffer from overexposure to books that can excite the

passions,

they had to read in secret. Borrowing a book from a library was safer

and more

practical than buying it. Consequently, circular libraries sprang up

all over

Europe. The first circulating library in London was established after

1740, and

it contributed to an increase in number of readers. Still, much cheaper

and

more popular than novels were innumerable entertainments such as plays,

operas

and masquerades. While the cheap books and poetry were read in veillées

[social evenings by the fire], novels required silence, comfort and

isolation.

The veillées also secured symmetrical positions of

author and reader in

silent communication. According to Barthes, the pleasure of the text

largely

derives from this magic distance between the author and the reader

imposed by

the medium of the printed book or a distance which guarantees their

respective

privacy. For this purpose, new kinds of furniture were invented.

Heroines of

the novels are often shown reading in a boudoir, that is a

private space

in a Georgian house, adjoining the bedroom, and consisting of a writing

desk. Virginia Woolf called it `a prime requisite of woman`s

emancipation`.

As the confidence of the

middle class was rising,

authors came from all kinds of backgrounds. Emma Bovary herself, had prix

de

lecture, which she shows to Charles when they meet. Sometimes, they

wrote

very explicitly and tautologically, so that the less educated readers

could

understand. With the development of print, author and reader began to

find

themselves in symmetrical positions, ‘silently communicating with

each other

through the printed text, often over many centuries` (Couturier

1991:-46).

The difference in

authors’ education and ability

explains some of the technical weaknesses of the written production.

But this

was not the case with Balzac, Flaubert and Zola. The middle class

proved to be

the most self confident at this time, and new standards of form and

content

appealed to large audiences and corresponded to the new public

indigence. In 18th

century England annual production of novels increased from seven at the

beginning to 80 at the end of the century. In 19th century

England

and France, the new taste for sentimentalism and gothic horror, both

provoking

easy indulgence, began to correspond to public requirements.

In France, the relation

between the literature and

life in fiction remained more distant than in England. Mme de Staël in her famous essay De la littérature in 1800 writes about the

literary rapport with

social institutions. There is the close connection between the French

realists

who wrote in the beginning of the century and romanticists who wrote

later, and

both demonstrate emphasis on individualism and originality.

Zola

and the End of the Century

Rhetoric, persuasion, and

competition of ideas enter

fiction that becomes more politically active. L`Education

Sentimentale

by Flaubert, repeated inherited slogans of 1789, and in the context of

the

nineteenth century, we have the example of `un roman qui aura pour

cadre le

monde ouvrier` [the novel that gives the context of the world of

the

working class] like Gérminal, a

claustrophobic novel about the mine-workers` strike. Objectivity and

truth of

representation in Zola’s work were more striking than in the

realist novels of

the time. Zola was writing as part of the literary movement of

Naturalism,

where the aim of the novel was to record fact. Naturalist writers

refuse

sentimentality and sensationalism.

In the 1877 preface to L`Assommoir,

`Zola

defends himself against criticism of the vulgarity of much of the

language`

(Flower 1983: 20 and 9). Dialogue was charged with exclamations,

dropping syllables,

popular expressions and slang. Themes were rape, ugliness, alcoholism

and

murder, while backgrounds were markets and factories. Although the

descriptions

had moral, social and political weight, the narrator remains detached.

For

instance, at the end of Gérminal, Etienne leaves Montsou

and the

surrounding region, and whatever hope there may be that the social

revolution

will one day come about, the mine has been reopened. He finds out, in a

kind of

self-exploration that he missed the intellectual capacity and

resolution in

order to be the leader, and he decides to go to university.

Re-establishment of

bourgeoisie control takes place and there is no alternative for the

workers.

`The new faculties of arts

and science set up by

Napoleon in 1808 had for decades virtually no students in the modern

sense of

the term but they were, in fact, strengthened in 1880s’ (Lough

1978: 281). In

his writings, Zola analysed the collective consciousness of the

working-class.

He drew attention to their miseries and suffering and portrayed l`odeur

du

people. Unlike bourgeoisie literature, ‘the language of

political

revolution is in principle directed towards turning the sphere of

public

discourse into a democratic forum, and the issues and forms of

contestation

become the most important` (Prendergast 1992: 25). Although the

working-class

press existed earlier in 1830s and 1840s with newspapers like L`Atélier,

the industrious worker was a new figure on literary scene, and Zola`s

argument

was that workers were victims and powerless to struggle for a better

life.

The Court of Appeal during

the Zola affair

Working-class female

characters of naturalist novels

often found comfort in religion (Flower 1983: 13). Fear of law was

generally

present and characters were often totally degraded, depraved of

intelligence

and the chance to rise above mediocrity. There is the strong criticism

of

bourgeoisie, who `for their part, distanced themselves rigorously from

the

people` (Habermas 1989: 72). Zola worked as a journalist and for Hachette

publisher,

where he became increasingly aware of the problems in society. His

transition

from journalism to the literary world was certainly favourable because

‘there

would always be more respect for authors of books than for the mere

journalist’

(Zeldin 1977: 506).

Commercialisation of the

press imposed and

encouraged a uniform and standard French. The spread of literacy inside

the

country was improved by better roads and the development of the

national

railway. The technological revolution helped expansion of books,

periodicals

and newspapers, and stimulated the growth of reading public. In the

course of

Dreyfus Affair,[8]

Zola published ‘J`accuse’,

a vehement open letter in a Paris Newspaper in 1898 and defended

Dreyfus, who

was accused of spying for Germany, which led to the case being

reopened. At the

time, Jews were generally considered people without fatherland and

insufficiently loyal to the countries where they lived. Dreyfus was

sentenced

to life imprisonment and a crowd emerged with anti-Semitic press,

shouts and

slogans. Nevertheless, in politics, bureaucracy and industry,

favouritism and

personal recommendation remained of great importance.

The conviction was a

miscarriage of justice based

upon espionage and anti-Semitism, particularly in a social context

conducive to

hatred of the German Empire following its annexation of Alsace and part

of

Lorraine in 1871. The implications of this case were numerous and

affected all

aspects of French public life: politics (the affair established the

triumph of

the Third Republic and became its founding myth), the renewal of

nationalism,

both military and religious (it slowed the reform of French Catholicism

and

republican integration of Catholics), social and legal domain, press,

diplomacy

and culture. However, the opposition served the republican order

according to

most historians and there was indeed, remarkable strengthening of

parliamentary

democracy and a failure of monarchist and reactionary forces. The

affair

engendered numerous anti-Semitic demonstrations, which in turn affected

the

emotions within the Jewish communities of Central and Western Europe.

After

France was split in two by this affair, with the conservative

government,

church and army on one side, and progressive critical forces on the

other, Zola

in fact managed to save Dreyfus who was declared innocent of the

charges decade

later. In 1896, Theodor Hertzl, a Jewish journalist from Vienna, who

covered

the trial, published a book The Jewish State,

where he expressed the opinion that Jews would remain

strangers in their countries of residence and that they needed the

country of

their own. It marked the beginning of Zionism.

Conclusion

Maurice Couturier described

the rise of the novel as

a ‘textual communication’ and he points out Lacan’s

theory which insists on the

role of the author and Foucault’s analysis of discourse. He calls

it the ‘most

subversive product of the typographic age’ (Couturier: 32) whilst

referring to

the omnipresent necessity of the time to create written language that

was

appealing to learning and recognition. Additionally, the development of

journalism increased the role of textual communication in social

communication.

The rise of the novel and journalism both caused the changes in the

organisation and the nature of the reading public and the general

interest in

reading increased, but still far from the nowadays phenomena of the

mass

reading public and mass communication. According to analysis by Watt,

the

newspaper buying public in nearby England tripled by the middle of the

19th

century from less than one newspaper buyer in 100 persons per week.

The social and political

environment in which the

novel appeared and in which literature experienced the break with the

old-fashioned romances, involving traditional plots of classical,

renaissance

epic, myth, legend or history, matters for the communication-oriented

approach

to fiction:

The novel attempts to

portray all the varieties of

human experience, and not merely those suited to one particular

literary

perspective. Its realism does not reside in the kind of life it

presents but in

the way it presents it. French Realists drew attention to an issue

which the

novel raises more sharply than any other literary form and the main

problem of

the correspondence was the one between the literary work and the

reality which

it imitates. (Watt 1957:11)

Realists built on the

philosophical ideas of Locke

and Reid in order to attain the fidelity of human experience, and the

idea was

that the truth can be discovered by individual through his senses.

Lynn Hunt analysed the

political culture of the

French Revolution and its consequences, as well as the accompanying

adequate

system of representation in institutions and symbols used in this new

political

discourse. Speaking about fiction, she argues that textual

communication

prevails because the novelist remains more engaged with the text and

less with

the audience. However, the author can transform the oral communication

into

written by weaving it into his fictional story and once the book is

available

to the reader, this fiction becomes a powerful tool of social

communication.

The cases of Balzac’s

opus, Flaubert’s trial and

Zola’s defence of Dreyfus remain illustrative of the novel as a

medium of

social communication in 19th century France, by showing how

the

language used in novels reflected the language of the society, the

customs,

interior and exterior decors, architecture, even political movements

and

opponents. ‘The novel’s conventions make much smaller

demands on the audience

than most literary conventions, and this surely explains why the

majority of

readers in the last two hundred years have found in the novel the

literary form

which most closely satisfies their wishes for a close correspondence

between

life and art’ (Watt 1957:32-33).

Politics connects with

fiction more intensely

through political happenings like the Dreyfus affair, which causes

refashioning

of the society, and makes stronger social references to the customs of

the past

and regenerating nation or nations, in this particular case, French and

Jewish.

Alternatively, this gives rise to self-conscious political principles

that we

can trace back to the writings of the Enlightenment thinkers that were

common

to many educated people like Zola. Writers of this period became like

brokers

of culture, people whose profession is of prominent social standing and

therefore

more capable of directly playing a role in social communication,

through their

writings or their intellectual position. This entire process of

interaction

among writer and reader, society, reality, imagination, as well as

language,

constitutes what we call social communication.

References

Academy

(2002), Vol.28, Le Père Goriot (Book Review), p.84-88

Calhoun,

Craig Ed. (1992), Habermas and the Public Sphere

(Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press)

Censer,

Jack Richard (1994), The French Press in the Age of Enlightenment,

(London: Routledge)

Chartier,

Roger (1991), The Cultural Origins of French Revolution, (Durham,

N.C., London: Duke University Press)

Couturier,

Maurice (1991), Textual Communication: A Print-Based Theory

of the Novel, (London and New York: Routledge)

Darnton,

Robert (2000), `An Early Information Society: News and the Media

in Eighteenth-Century Paris`, American Historical Review,

Vol.105, pp.

1-35

Darnton,

Robert (1979), The Business of Enlightenment (Cambridge,

Massachusetts, and London, England: the Belknap Press of Harvard

University

Press)

Day,

Geoffrey (1987), From Fiction to the Novel, (London and New

York: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.)

Emerson,

Ralph Waldo (1913), `Essay on Napoleon`, Essays and

Representative Men, Vol.1 (London: g. Bell and Sons, Ltd.)

Faure,

Alain (2004), `Paris, «gouffre de l`espèce

humaine» ?`, French

Historical Studies, Vol. 27, No.1, pp.49-86

Fiedler,

Klaus (2007), Social

Communication: Frontiers in Social Psychology (New York, USA and

Hove, UK:

Psychology Press)

Flower,

J.E. (1983), Literature and The Left in France: Society,

Politics and the Novel since the Late Nineteenth Century (London

and

Basingstoke: The Macmillan Press)

Grenby,

M.O.(1998), `The Anti-Jacobin Novel: British Fiction, British

Conservatism and the Revolution in France`, The Historical

Association,

(Blackwell Publishers: Oxford)

Gilchrist,

J. and W.J.Murray eds. (1971), The Press in the French

Revolution (Bristol: Western Printing Services Ltd)

Habermas,

Jürgen (1989), Structural transformation of the Public

Sphere, (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press)

Hall,

Gaston (1961), `Balzac, »Le Père Goriot», ed. by P.

G. Castex (Book

Review), Modern Language Review, Vol.56, No.2, p.311

Hunt,

Lynn (1986), Politics, Culture, and Class in the French

Revolution, (London: Methuen)

Iknayan,

Marguerite (1961), The Idea of The Novel in France: The

Critical reaction 1815-1848 (Genève: Droz)

Lefebre,

Georges (1973), The Great Fear of 1789: rural panic in

revolutionary France,

(London:

W1, NLB)

Lough,

John (1978), Writer and Public in France, From Middle Ages to

the Present Day (Oxford: Clanderon Press)

Mason,

Laura (1996) Singing the French Revolution: Popular Culture and

Politics, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press)

Moretti,

Franco (1998), Atlas of the European Novel 1800-1900

(London and New York: Verso)

Smith,

Edward C. (1999), ` Honoré de Balzac and the

«Genius» of Walter

Scott: Debt and Denial, Comparative Literature Studies, Vol.36,

No.3,

pp.209-225

O`Boyle,

Leonore (1968), ` The Image of the Journalist in France,

Germany, and England, 1815-1848`, Comparative Studies in Society

and History,

Vol.10, No.3, pp.290-317

Prendergast,

Christopher (2000), The Triangle of representation,

(New York, Chicester: Columbia University Press)

Prendergast,

Christopher (1992), Paris and the Nineteenth Century,

(Cambridge, Massachusetts, Blackwell Publishers)

Prendergast,

Christopher (1986), The order of Mimesis: Balzac,

Stendhal, Nerval, Flaubert, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Prendergast,

Christopher ed. (1990), Nineteenth century French poetry:

introductions to close reading, (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press)

Prendergast,

Christopher (1978), Balzac: fiction and melodrama,

(London: Edward Arnold)

Sharon,

Marcus (1999), Apartment Stories: City and Home in

nineteenth-century

Paris and London, (London, Berkley and Los Angeles: University of

California Press)

Terdiman,

Richard (1985), Discourse/Counter-discourse: the theory and

practice of symbolic resistance in nineteenth-century France

(Ithaca, N.Y:

Cornell University Press)

Tartakowsky, Danielle (2004), `

La construction sociale de l`espace politique: Les usages politiques de

la

place de la Concorde des années 1880 à nos jours`, French

Historical Studies,

Vol.27, No.1, pp.145-173

Watt,

Ian (1957), The Rise of The Novel : Studies in Defoe,

Richardson and Fielding, (Berkley and Los Angeles: University of

California

Press)

Zeldin,

Theodore (1977), France 1848-1945, Vol. 2, Ch.11,

(University Press: Oxford)

[1] Many thanks to members of my family and colleagues at previous and present working places and universities for their support; to professor Dr. Stephen Lovell, for help finding suitable Bibliography, whilst supervising the first version of this article, written as a longer text for the course Communications in Modern Europe; and to the Philosophy Department of Warwick University for a warm welcome at the Literary Conference held in March, 2014, Theories of literature: Essence, Fiction and Value and for sharing with us the relevant information about the Exchanges: Warwick Research Journal and other literary - research publishers.

[2]

See Klaus Fiedler’s Social Communication

for examples of such definitions of ‘social communication’.

[3] This translation into English contained in the square brackets (and all other similar translations) in this article were made by myself, whereas I left the more commonly used French terms which reappear in use in the English language and whose meaning remains known or easy to guess for a reader in italics and without translation. The titles of works originally published in French and French institutions are also given in italics and in French.

[4] The

colonialist

expansion contributed to another characteristic of France during this

period.

Consequently, both culture and language made their impact in the new

territories, establishing a kind of two-way colonisation-discourse

(i.e. both

the colonised territories and the colonisers influenced one another)

which

extended throughout the 19th and 20th century.

[5] Paris

gained its

political significance because of the fact that the Revolution brought

back the

seat of government from Versailles. It was the time of mercantilism,

capitalism

and mobility of wealth. Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann, completely

transformed

the French capital into a physically more coherent and true Western

metropolis.

Paul Verlaine, who often wrote about urban boredom, said about the

architecture

of Haussman that it was bric-à-brac confus. New

architecture demolished

the slums, made boulevards, refurbished facades and expanded parks, as

the

spaces where people could meet and talk.

[6] Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes` makes up part of Balzac’s Comedié Humaine and it is preoccupied with the underworld. Zola’s Nana shows `uneasy interaction between high society, theatre and prostitution` (Moretti 1998: 90).

[8] The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal

that divided France for about 12 years, from the affair's inception in

1894

until its resolution in 1906. The affair is often seen as a modern and

universal symbol of injustice for reasons of state and remains one of

the most

striking examples of a complex miscarriage of justice.