A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words

Examining learners’ illustrations to understand Attitudes towards

Mathematics

Farhat Syyeda, University of Leicester

Abstract

This

article presents my experience of using pictures/images drawn by children as a

form of data in research and discusses the merits and implications of employing

this method. It comes from research of a mixed method exploratory case study to

investigate the attitudes of 11 and 15 year old secondary school students (in

the East Midlands) towards Mathematics. The aim of this research was to gain an

insight into the emotions, cognition, beliefs and behaviour of learners

regarding Maths and the factors which influence their attitude. Besides using

the tried and tested data collection tools such as focus groups and

questionnaires, the children were asked to draw pictures illustrating their

vision of Maths and its impact on their lives. The idea was to offer them an

alternative medium of communication to exhibit their feelings and thoughts.

Students used emoticons, numerals, figures, characters and mathematical symbols

to show their favourable/unfavourable attitudes towards Maths and their

understanding of the importance of Maths in future life. The results of visual

data in this study conform to the findings of the other forms of data collected

and show that boys and higher ability students have a more positive attitude

towards Mathematics as compared to girls and low ability students.

Key

Words: visual data, images/drawings, case study, attitudes, affect, cognition

Introduction

This article is a part of a larger

study to understand learners’ attitudes towards Mathematics and to investigate

whether attitudes are related to age, gender, academic attainment level, socio

economic status or linguistic background of the learners. The visual data

presented in this article was used in combination with other forms of data to

draw conclusions for the study. The purpose of this article, however, is to

analyse the use of children’s drawings as a form of data in research and to

discuss the merits and implications of using this instrument. The participants of this mixed method

exploratory case study were year 7 and year 10 students belonging to diverse

linguistic back grounds, socio economic status and attainment levels in Maths.

This article comprises of two main sections: the first section examines

relevant literature about the use of drawings as data in detail, whereas the

second section discusses my experience of using visual data to study attitudes

towards Maths.

It is vital to regard students’

opinion in educational research in order to comprehend their perspective and

preferences. The UN convention on the rights of the child (1989) emphasizes the

inclusion of children’s voice in matters concerning their lives. DfES (2001)

also encourages students’ participation in decisions about their learning.

Collecting data from children is a formidable task as some of them are not

comfortable in conveying their opinion in words (speech or written form) due to

lack of confidence, limited vocabulary, learning difficulties, poor spellings

or weak written and verbal expression. Thus their viewpoint may remain unrepresented and unknown. In this research an

innovative method was employed to address this problem and visual data sketched

by the participants in the form of pictures/images/drawings was gathered.

Visual

data in research

An image/visual/picture is a nonverbal

mode of expression worldwide and provides an alternative and complementary tool

of communication. Drawing is a popular and engaging activity among children all

over the world which can be employed to elicit useful data in a fun and affable

way unlike questionnaires which may create test like situation and cause

anxiety (Bekhit et al., 2005). It’s a quick and efficient method to collect a large

amount of data (MacPhail & Kinchin, 2004) in a short span of time. Drawings

provide a multi-dimensional view of children (Malchiodi, 1998) and offer a

unique way of discovering their perceptions. Through their drawings children

may portray their feelings and emotions, their knowledge and understanding,

their vision of the world around them and their experiences. They draw what they see (visual realism) and

what they know (intellectual realism) (Cox, 2005).

The greatest advantage of drawings is

that they are child centred (Merriman & Guerin, 2012) and child empowering.

Children can draw whatever they wish to share and whatever they consider

important without any prompting or instruction (Einarsdottir, 2009). Since

drawing is a universal language, it can be used as a data collection tool among

children from different countries and cultural back grounds; avoiding the

hassle of translation between languages and interpretation of transcripts.

Drawings have been successfully used to extract data from street children

belonging to deprived families in India who have never been to school and

cannot read or write (Merriman & Guerin, 2012).

Drawings are commonly used in research

in clinical psychology to collect information about a range of psychological

and emotional aspects in children including personality traits, mental

development and neurological disorders (Thomas and Jolly, 1998; Bekhit et al,

2005). In the field of Education, drawings have been used to explore children’s

attitudes towards different subjects taught at school (Smith, 2011; MacPhail &

Kinchin, 2004), national identity (Durrani, 2008) and perceptions and

experiences about being at school (Einarsdottir et al, 2009).

Despite all the advantages, pictures

drawn by children are very complicated and should be used as data with caution.

Burkitt (2004) observes a link between the vision and attitude of a child and

the size of figure that he/she draws.

Large size normally depicts a happy, positive, socially important and

pleasing figure. However, it does not imply that a smaller figure means a negative

image. Also, a child’s sense of proportion and skills as an artist can affect

the size and scale of the picture/drawing (MacPhail & Kinchin, 2004).

Colours are quite often associated

with moods and emotions. Bright, bold colours like red, yellow and orange are

normally viewed as cheerful and positive whereas dark colours such as purple,

black and brown are presumed to show distress. Nevertheless, the selection of

colours can be related to personal liking or feeling towards a particular

colour and may have nothing to do with a jovial or gloomy image (Burkitt et al.,

2003).

Children may express their feelings,

emotions and attitudes in their drawings; however they may not be depicted in a

consistent and reliable way (Burkitt, 2004). Children belonging to different

cultures and educational backgrounds may use the same colour or image to

represent contrasting meanings. Therefore it is not advisable to use drawings

as ‘sole indicators’ of children’s emotions as they can be interpreted in

numerous ways (Thomas and Jolley, 1998).

‘A child psychologist once

scoffed at the notion proposed by some that the children at Bellevue painted

boats on the water because it symbolised the separation from their mothers,

making the point with some scorn that they drew boats because the hospital was

on the East River and that was all they saw!’

(Rubin, 1984: 45) quoted in Merriman & Guerin, (2012).

Because of the challenges in

interpretation and analysis, pictures are not a very reliable instrument for

gathering data. To understand the drawings they can be used in combination with

other tools for example follow up interviews with the illustrators asking them

to talk through (Einarsdottir et al., 2009) and interpret their drawings, but

it may be more time consuming. Children can also be asked to annotate or label

the drawing to make their meaning clearer. Some researchers observe and listen

to the children while they are drawing (Cox, 2005) to understand the thought

process going on in their minds.

Recent research recognises the value

of drawings not just as a ‘visual reference’ to real objects but as a

‘constructive process of thinking’ (Cox, 2005: 123) and meaning making which

cannot be understood in isolation from its social and cultural context.

Drawings narrate and communicate children’s understandings and experiences in

their specific contexts; therefore it’s imperative to focus not just on the

image but the message it conveys and the meaning it entails (Einarsdottir et

al, 2009).

Examining

learners’ drawings to study Attitudes towards Maths

The purpose of this research was to

understand attitudes towards Maths among year 7 (KS3) and year 10 (KS4)

students in a major city in the East Midlands and to investigate whether age,

gender, academic attainment, socio economic status or linguistic background had

any impact on attitudes. Attitude is a complex term and for this research it

was defined as a combination of three components namely: Affect (emotional

disposition, belief and vision about the subject), cognition (perception of

usefulness of the subject) and behaviour (intentions, commitment and

performance in the subject).

To select the research participants, a

purposive sampling technique was employed and of the 38 schools listed on The

Department of Education’s website, 13 schools were shortlisted. These 13

schools were further grouped on the basis of the attainment level of students

in GCSE exam, the percentage of students claiming free school meals (FSM) and

the percentage of students with English as a second language (ESL). The plan

was to include four schools in the research however, although all the 13

schools were contacted, only 2 schools agreed to allow access to their students.

To select the students within schools, again a purposive sampling strategy was

adopted and high ability and low ability learners, girls as well as boys and

year 7 and year 10 students were represented.

For this research four kinds of data

were gathered to investigate attitudes towards Maths in two phases. In the

first stage, qualitative data through focus group discussions was collected on

audio tape. Focus groups are interview style group discussions involving a

small number of participants (usually between four and twelve) guided by a

facilitator or moderator (Barbour, 2008). For this research, focus groups were

the most suitable tool for collecting qualitative data because focus groups are

held in an informal atmosphere which encourages the participants to speak

openly and freely about attitudes, opinions and behaviours. Since the

participants of this research were young students between the age of 11 and 15

years, individual interviews in a formal style would not have been a good

choice. The children could feel intimidated or pressured and concerned about

being evaluated by the interviewer, thus withholding their inner feelings.

However, these effects are diluted in a group setting because the respondents

feel empowered as the burden of answering is distributed (Berg, 2009). For this

research, four focus groups were conducted in two different schools in which

sixteen students participated. Data collected through focus groups was also

used as a stimulus to design the questionnaire.

Focus groups generate a good amount of

data in a short span of time but give a collective view of the participants.

Therefore, to get an insight into the perceptions, personal feelings and

thoughts of the students individually, the second phase of the research

consisted of anonymous questionnaires. The questionnaire was purposely designed

to collect quantitative as well as qualitative data. It contained closed

questions to measure preferences on a Likert scale and open ended items asking

the learners to write a passage or draw a picture about their vision of Maths

and its impact on their lives. The aim was to elucidate maximum data by

providing alternate media of expression to include visual learners and those

who are not fond of extended writing. Keeping in mind the complexities of

interpreting pictures, the children were asked to annotate their illustrations.

Moreover, the researcher remained in the same classroom with them while they

were drawing and asked the artists to describe what they had sketched wherever

possible.

General

findings of the study

The data gathered for this study

indicates that attitudes towards Maths are affected by gender and attainment

level. The Likert scale clearly shows that boys have a more favourable

emotional disposition towards Maths (Mean value µ = 1.76 where 1 is positive

and 3 is negative) as compared to girls with a mean value of 2.19. The

cognitive aspect of attitude is also more positive in boys (µ = 1.26) than

girls (µ=1.5). Similarly high ability learners have a mean value of µ=1.75 for

affect and µ=1.27 for cognition whereas the low ability learners have µ

(affect) = 2.18 and µ (cognition) = 1.49. These differences in means are

statistically significant (t-tests were conducted). Other factors such as age,

socio economic status and linguistic back ground also influence affect and

cognition towards Maths but do not impact them significantly.

Interpreting

images drawn by the participants

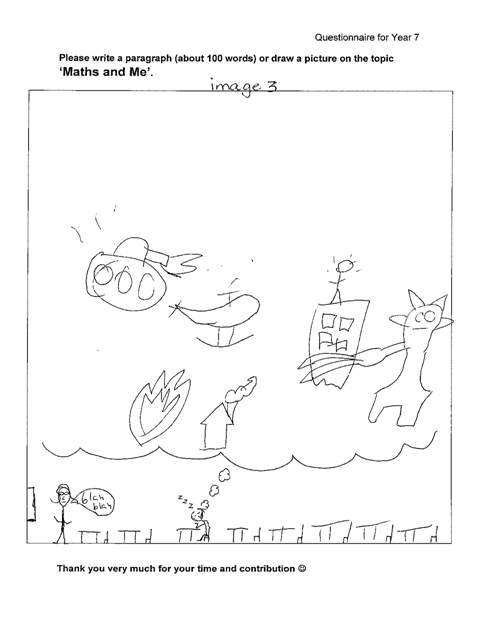

A total of 187 students filled in the

questionnaires; however the number of students who chose to draw pictures was much

smaller (about 10%). This indicates that drawing is not a preferred mode of

communication for all the children (Einarsdottir et al., 2009). Some children

used a combination of words and images such as emoticons (smiley and sad faces)

and thumbs up and down signs to demonstrate their favourable or unfavourable

attitudes towards different aspects of maths.

Nevertheless, a few pictures (presented in this article) were more detailed and

depicted the perceptions of learners beautifully.

The images/drawings made by the

learners were interpreted using a holistic approach (MacPhail & Kinchin,

2004) considering the content as well as the context of the drawings and

keeping in mind the theoretical framework of the research. These images were

also shown to other researchers and doctoral students for discussion before

arriving at the following interpretations.

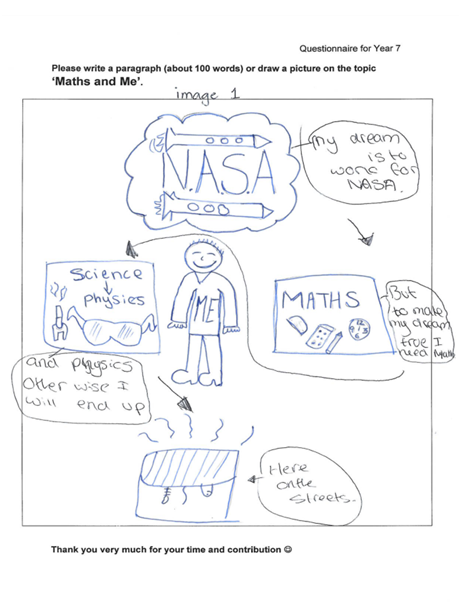

Images 1 and 2 describe the importance

and usefulness of Maths in personal and professional life. These two images are

related to the cognitive component of attitude whereas the emotional aspect is

not mentioned. Image 1 makes the assertion that knowledge of Maths (along with

science) can help this child get his dream job which is to work for NASA but

without Maths he would be useless and

may end up on the street in a bin. The child does not explicitly show his

liking for the subject (other than the big smile) but has a clear understanding

that Maths is important for his career in future.

Fig 1: Image 1

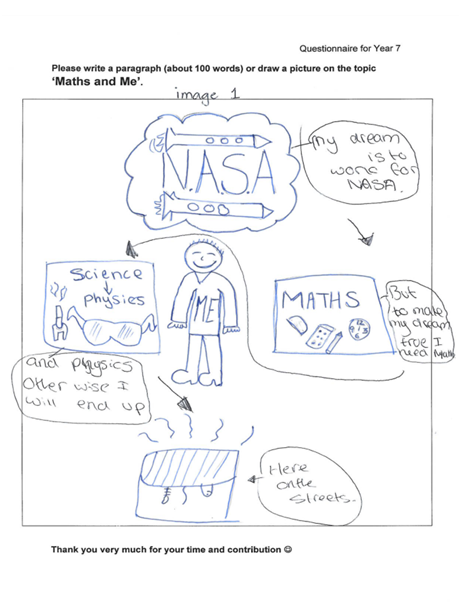

Image 2 highlights that Maths is not

only needed in job and everyday life; it also helps in ‘developing your thinking of the world’. This image also underscores

the importance of Maths (cognitive aspect) but does not express any feelings or

emotion towards the subject.

Fig 2: Image 2

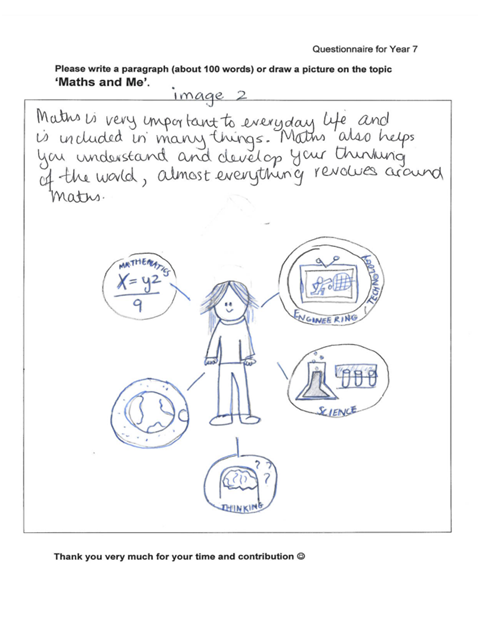

The emotional disposition of the learners in a typical classroom setting is depicted in the next three images. In image 3, the scale of the drawing is noteworthy. The actual classroom is diminutive in comparison to the imagination of the child (all images were drawn on A4 sheets). The teacher has a stern expression on her face and the words uttered by her do not convey any meaning to the learner (blah, blah, blah). The child is completely distracted and snoring (zzz).

Fig 3: Image 3

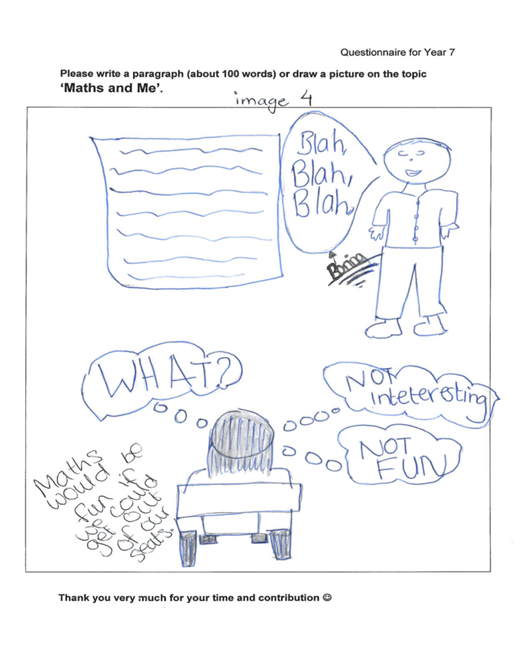

Image 4 portrays a lack of connection

between the teacher and the student. The student is unable to follow teacher’s

explanations (blah, blah, blah /what?).

She feels restricted and confined to her seat which seems to be rooted to the

ground (legs of the chair drawn in bold). She is unengaged and bored.

Fig 4: Image

4

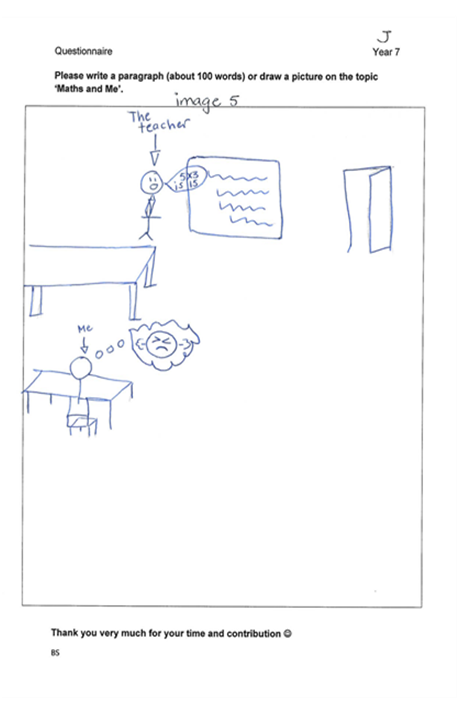

Image 5 shows the teacher with a

pleasant countenance (a smiling face) which suggests that the learner has a

positive impression about the teacher. Her words are also not meaningless (5x3=15 makes sense). Nevertheless, the

student seems to be vexed. The learner’s affect towards Maths according to his

Likert scale data is positive or favourable, although he is from the low

ability cohort. Thus the frustration could be due to the lesson being pitched

at a level below his intelligence or the teacher going into too much detail and

explaining the obvious (5X3=15).

Fig 5: Image 5

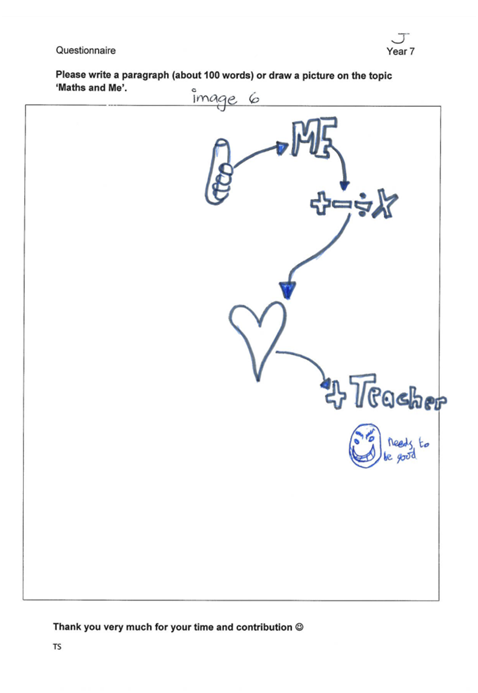

Image 6 displays positive emotions

towards Maths (sign of heart <3), however this love for Maths is conditional

upon the teacher being good.

Fig 6: Image 6

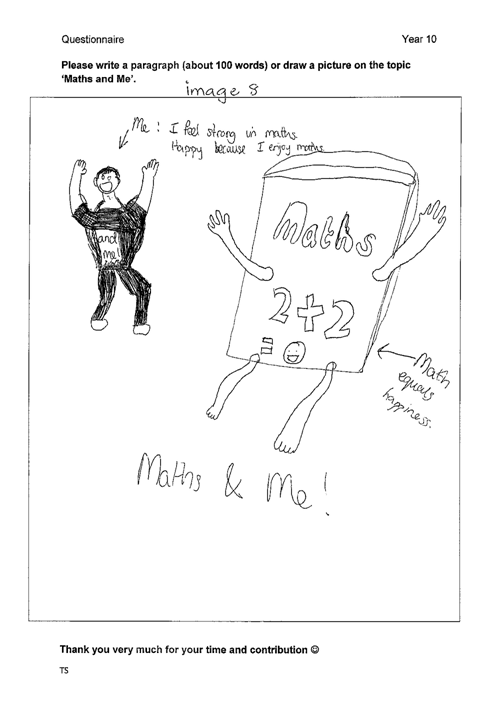

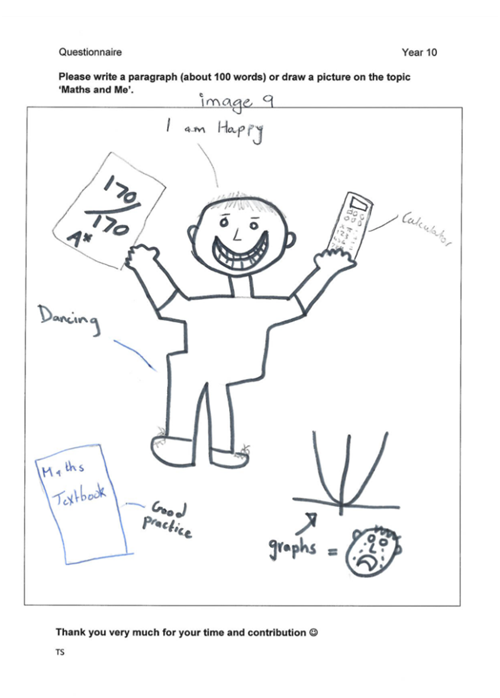

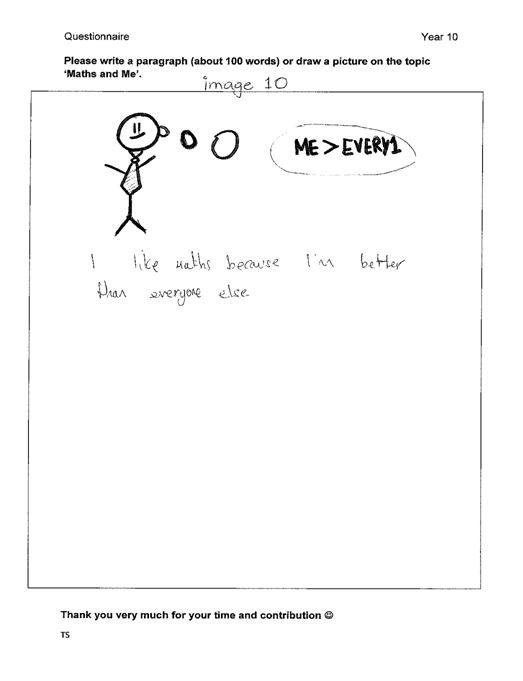

Image 8, 9 and 10 are drawn by high

ability year 10 boys and demonstrate a high level of confidence, pride and

self-esteem. Image 8 shows a proud and

jubilant student (Maths equals happiness)

with his Maths book, who feels totally in command to tackle all the

problems/assignments in Maths (strength shown by muscles).

Fig 7: Image 8

Image 9 depicts joy and celebration in

the form of dancing for achieving a hundred percent score in Maths (though

graphs are a weak area and make the student cry).

Fig 8: Image 9

Image 10 shows self-contentment and

pride for being the best students in the class and being superior and better in

Maths than everyone else (ME > EVERY1). The students seems to have a

positive self-concept and his positive disposition towards Maths is related to

his achievement (I like Maths because I

am better than everyone else).

Fig 9: Image 10

Discussions

and Conclusion

The attitudes demonstrated in the

images seem to be in consonance to the trends highlighted through other forms

of data collected for this project. The findings of this research show that

high ability learners and boys have a positive attitude towards Maths which is

statistically significant as compared to low ability learners and girls. Other

factors such as age, socio economic status and linguistic back ground also have

an impact on attitudes but it is statistically insignificant.

It’s interesting to note that less

than 10% of the 187 students who participated in this research chose to express

themselves visually in images/drawings and most of them were boys and high

ability students. In my sample, 75 out of 187 students were girls (about 40%).

However, of the nine images shown here, only two (image 2 & image 4) were

drawn by girls (about 22%); one from the high ability and the other from the

low ability cohort. Similarly, 78 out of 187 (about 42%) students were from the

low ability cohort but only two low ability students, one of them a girl drew

pictures (image 4 & image 5). The contact time allowed with the students in

this research was very short; only twenty five minutes. Thus after completing

the Likert scale questions, students were left with only fifteen minutes to

write a passage or draw an image. This could be a reason for the low response

rate. Pictures are an interesting

medium to study children’s perceptions but unfortunately learners becomes less

enthusiastic about drawing as they grow and move up in school (Anning, 2002).

In my sample more pictures were drawn by year 7 students as compared to those

in year 10. Therefore this instrument is more effective in collecting data from

younger children.

References

Anning,

A. (2002), ‘Conversations around young children’s drawing: The impact of the

beliefsof significant others at home and school’, Journal of Art and Design Education, 21(3),197–208

A

summary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989).http://www.unicef.org.uk/Documents/Publication-pdfs/UNCRC_PRESS200910web.pdf accessed on 22 December, 2014

Barbour,

R. (2008), Introducing Qualitative

Research: A Student's Guide to the Craft

of Doing Qualitative Research, UK:

Open University Press.

Bekhit,

N. S, Thomas, G. V. & Jolley, R. P. (2005), ‘The use of drawing for

psychological assessment in Britain: Survey findings’, Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 78,

205–217

Berg,

B. L. (2009), Qualitative Research

Methods: For the Social Science, Boston: Pearson Education Inc.

Burkitt,

E., Barrett, M. & Davis, A. (2003b), ’The effect of affective

characterisations on the use of colour within children’s drawings’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,

44, 445–455.

Burkitt,

E. (2004), ‘Drawing conclusions from children’s art’, The Psychologist, 17, 566-568.

Carey,

M. (2011), The social work dissertation:

Using Small-Scale Qualitative Methodology, New York: Open University Press

Cox,

S. (2005), ‘Intention and Meaning in Young Children’s Drawing’, International Journal of Art & Design

Education, 24(2), 115–125

Durrani,

N. (2008), ‘Schooling the ‘other’: the representation of gender and national

identities in Pakistani curriculum texts’,

A Journal of Comparative and

International Education, 38:5, 595-610

Einarsdottir,

J., Dockett, S. & Perry, B. (2009), ‘Making meaning: children’s

perspectives expressed through drawings’, Early

Child Development and Care, 179:2, 217-232

Henderson,

N.R. (1995), ‘A practical approach to analysing and reporting focus groups studies:

lessons from qualitative market research’, Qualitative

Health Research 5, 463-477

MacPhail,

A. & Kinchin, G. (2004), ‘The use of drawings as an evaluative tool:

students' experiences of sport education’, Physical

Education and Sport Pedagogy. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1740898042000208142 Accessed on 15 October, 2014.

Malchiodi,

C. (1998), Understanding Children’s

Drawings, New York: The Guilford Press

Merriman,

B. & Guerin, S. (2012), ‘Using Children’s Drawings as Data in Child-Centred

Research’, The Irish Journal of

Psychology, 27 (1-2), 48-57.

Sim,

J. (1998), ‘Collecting and analysing qualitative data: issues raised by the

focus group’, Journal of Advanced Nursing,

28(2), 345-352

Smith,

C. (2011). Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning

Mathematics (Ed.) 31(1) Available at: www.bsrlm.org.uk Accessed on 6 June, 2014

Thomas,

G. V. &Jolley, R. P. (1998), ‘Drawing conclusions: a re-examination of

drawings’, Journal of Clinical Psychology,

37, 127–139.