Jacqui

Shepherd

ESRC PhD student, School of Education and

Social Work, University of Sussex

Abstract

This article examines the methodological

approaches used in a research project that investigated the lived experiences

of young people with autism and learning difficulties as they made the

transition from special schools to mainstream colleges of Further Education.

A combination of visual methods, using tablet

applications and walking interviews were explored in an attempt to develop ways

of engaging young people with autism in research and to privilege their voice

in their own transition. The effectiveness and limitations of these methods are

examined here and illustrated through the experience and responses of one young

person in the study and his engagement with the research.

Keywords:

transition; autism; special school; further education; visual methods; learning

difficulties; walking interviews

Introduction

This longitudinal research set out to

understand the experience of transition from the point of view of young people

with autism as they left special school and started at mainstream college. Whilst potentially

unsettling for any young person at this age, this transition can be

particularly challenging for young people with autism, knowing that an

‘anxiously obsessive desire for the maintenance of sameness’ and a ‘dread of

change’ are likely characteristics of autism (Kanner 1943: 245). The

focus of this study was on the transition from a small special school

environment to one of a large mainstream college. All the young people involved

in the study had both autism and a degree of learning difficulty that had

necessitated a statement of special educational need and a specialist

environment. The research was carried out against the

backdrop of a changing policy context where all young people are now expected

to stay in education or training until the age of 18 (DfE, 2008)

and, for young people with a new Education, Health and Care (EHC) plan,

potentially until the age of 25 (DfE et al., 2014). This

was also linked to an increasing emphasis on giving people with learning difficulties

a voice (UNCRPD, 2006) and developing more person-centred planning,

particularly in relation to transition arrangements (DfE & DoH, 2014). With this in mind, the research sought to understand

transition for young people with autism through developing appropriate methods

to listen effectively to their experiences as well as those of their

care-givers and related professionals. The

resulting ‘interrupted interviews’ based on these methods helped to give voice

to the individual participants and communicate their preferences and

experiences. This article focuses on the methodological approaches used in this

project and discusses their strengths and limitations as illustrated by a

single case study of one of the young people in the research.

Autism,

transition and adapted interviews

While a significant cohort of young

people with autism do now progress on to further education (Mitchell 1999; Breakey 2006; Chown & Beavan 2012), the

‘Finished at School’ Report suggested that ‘less than 1 in 4 young people with

autism continue their education beyond school’ (Ambitious About Autism, 2012: 8).

Breakey (2006) argued that reasonable adjustments have to be made for students

with autistic spectrum condition (ASC) when they make the transition to further

education, that pre-access preparation is essential to redress the balance

between them and their neurotypical peers and that many autistic students still

fail to access further education because of the lack of such provision. While

these adjustments have been identified, they do not yet seem to be wholly in

place, ‘with knowledgeable support there can be an improved prognosis for

persons with autism, however, such support is considered to be a rarity in

further education at present’ (Chown

& Beavan, 2012: 477).

Representing the experiences of

the young people in this project was particularly pertinent to its central core

as it sought to focus on the range and diversity of individual young people

with autism. Ways in which to do this ethically and constructively have been

explored in the literature, although there is no conclusive evidence for the

most appropriate method for interviewing people with autism (Lewis & Porter

2004; Nind & Vinha 2013; Palikara et al. 2009; Milton et al. 2012). This area of research is clearly in the process of

development although Preece, albeit writing in 2002, could find very little

published research that had included the direct participation of children with

autistic spectrum conditions.

While semi-structured interviews were an

extremely valuable instrument in gaining the views of the adults in the

research, they were not necessarily the most apposite choice for talking to

young people with ASC and additional learning difficulties. The diversity and

heterogeneity of this group potentially implied that they might not make eye

contact, might not have much language, might struggle with social situations, and

might be disconcerted or made anxious by the presence of strangers (Wing 1996). The

young people in this study all had different communication and social

interaction capabilities and difficulties so they were not a homogenous group. The premise in much of the research

methods literature is about the ability of participants to express themselves

clearly, thoughtfully and openly (Kvale & Brinkmann 2009; Gubrium & Holstein 2002; Weiss 1994) and that the ‘respondent is

someone who can provide detailed descriptions of his or her thoughts, feelings

and activities if the interviewer asks and listens carefully enough’ (Gubrium

and Holstein, 2002: 8). These premises do not necessarily apply to the

participants in this project. However, there was evidence

to suggest that visual stimuli or cue cards (Lewis et al. 2008) and

‘talking mats’ (Cameron & Murphy, 2002) could be helpful to support

communication with those on the spectrum, ‘this is the kind of practical visual

complement to open-ended approaches which is seen as particularly useful for

participants with autism’ (Nind 2009:10).

Potential methodological approaches were

explored in relation to literature on ASC and on research methods. Booth & Booth (1996) explored

the ‘excluded voice thesis’ in relation to people with learning disabilities

and identified four particular challenges when carrying out narrative research

which proved to be useful markers for considering interview research in this

project: inarticulateness which could relate to limited language skills as

well as anxiety in social situations; unresponsiveness

as they might find it difficult to answer open-ended questions; concrete frame of reference which might

be characterised by difficulty in generalising from experience and thinking in

abstract terms and similarly difficulty with imagining the future, and problems with time making it difficult

to order past events.

Preece (2002) identified very limited

research with children and young people with learning difficulties and proposed

that consultation with young people with autism had not considered the specific

impairments associated with ASCs. He concluded that aloofness, social anxiety,

poor memory and the limited and idiosyncratic use of language all impacted on

the ability of those with autism to participate in the consultation process and,

for this study, all these areas had to be taken into account. While there is

little known about which research methods might afford the best opportunities

for the participation of young people with autism (Harrington & Foster 2013), it

is incumbent on researchers to consider the individual, common and exceptional

needs (Lewis & Norwich 2005) of

the participants and design, and adapt methods accordingly. With this in mind, ‘interrupted

interviews’ that involved both the use of collages and card sorts on the tablet

were developed for the early interviews, and walking interviews around the

college environment were planned for the later data collection point.

The

research study

This ESRC funded doctoral

research took the form of a longitudinal case study approach over a ten month

period of data collection from June 2013, when the young people were preparing

to leave school, through to March 2014 when they had spent six months in their

new college settings. The sample comprised six young people with ASC from three

different special schools who progressed on to five different colleges of

further education. They continued on to a variety of courses including BTEC,

Foundation Learning and other vocational courses at different levels. The data

used in this article relates to one student, Jake, in order to illustrate the

methodological approaches used and their relative effectiveness and limitations

in listening to the views of young people with ASC.

Jake:

a case study

Jake is a young man with a diagnosis of

autism and moderate learning difficulties, who was in his final year at a

special school in the South of England when he was first interviewed. He had had a statement of special educational

needs since he started school and had always been educated in special

provision. He had good communication skills and was on the higher functioning

end of the autistic spectrum as evidenced by his progress at school and his

ability to interact well with his peer group and with adults. He was one of the

more able young people in the study, and was able to communicate in complex

sentences and answer open-ended questions in some depth. According to his

Learning Difficulty Assessment (also known as the Moving On Plan) he had difficulty in making

eye contact when stressed, difficulty with understanding facial expressions,

body language and tone of voice and struggled with words that had several

meanings. The ‘interrupted interviews’ helped to support the interview with

Jake and diluted the intensity of the interview scenario.

Jake was initially interviewed at school,

which took the form of a semi-structured interview punctuated by activities that

included making a collage and sorting cards into order of preference on the tablet.

Preece (2002) argued that visually mediated methods strengthened the

communication of young people with ASC in the consultation process. The collage

task required Jake to organize and select both his abilities and interests in

and out of school, as part of the focus here was to focus on his strengths and capabilities.

The images of typical school subjects were pre-loaded and he could remove them,

make them bigger and smaller according to his likes and dislikes, and move them

around. We added the words ‘swimming’, ‘drama’ and ‘media’ because he also wanted

to represent those activities that were partly undertaken outside school.

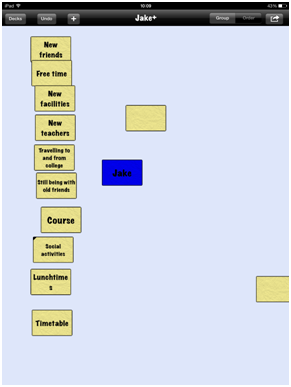

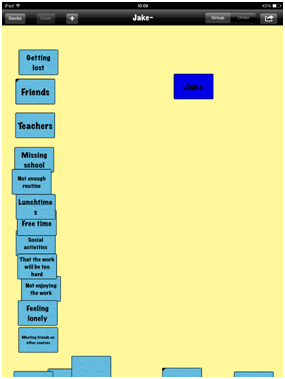

After some more questions about Jake’s

experience of special school and his preparation for college, a card sort

exercise was introduced. The individual cards held a list of pre-loaded words

or phrases (with some additional blank cards for adding his own ideas) and Jake

had to move the items into the order of perceived importance regarding what he

was looking forward to (Figure 3), and what he was worried about (Figure 4).

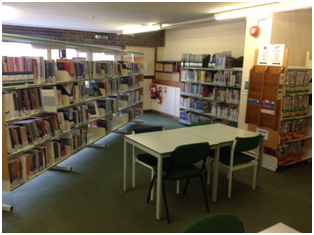

The second data collection

point took place during the Spring Term of Jake’s first year of college, and

after some interim emails during the first term. Jake was interviewed for 30

minutes at home and then during a ‘walking interview’ (Clark & Emmel 2010) at

college. The aim of the interview was to walk around the college environment, led

by Jake, to the places where he attended lessons and socialized in order to

build a picture of his college experience. He was given a tablet to take

photos of places at his college that were significant to him in some way (care being

taken not to include identifiable pictures of other students for ethical

reasons). An extract from the walking interview is given below (Figure 5) in

which Jake indicates how he uses the central facilities at college in his free

time between lessons:

Figure

5. Upstairs in the Learning Resources Centre

Researcher: So do you come in here if you have gaps in between lessons?

Jake : If I have gaps in between lessons,

I sometimes come in here…so yeah, take a picture there. Do you want to go

downstairs and take a picture?

Researcher: I

don't mind. Do you mostly go upstairs or downstairs?

Jake: I go downstairs but I sometimes go

upstairs, downstairs is where you can read the

books down there...[walking downstairs] ...so you've got the ICT, public services, you've got all sorts

of books there

Researcher: Right, that's really good isn't it?

Jake: I'll take a picture there...right

that's taken [takes picture of downstairs in LRC]

Figure

6. Downstairs in the Learning Resources Centre

Effectiveness

of the methods used

The use of activities on the tablet and also

the walking interviews helped to open up the discussion during the interview, especially

in the first interview when the researcher-participant relationship was newly

formed. Jake showed an interest in the tablet from the beginning of the

interview and was motivated to use it. Although his language skills were very

good and did not suffer from the ‘inarticulateness’ to which Booth & Booth (1996)

refer, he nonetheless had some limitations and idiosyncrasies in his use of

language (Preece, 2002)

which manifested as echolalia, for example,

Researcher: Have you got friends at school?

Jake: I have got friends at school...

and

Researcher:

Right so you're pretty fast then?

[swimming]

Jake: Yes, I'm pretty fast, yes

Using the activities on the tablet helped to

develop the interview into more of a conversation around the subjects that Jake

liked and the activities that he took part in outside school. The walking

interview also helped to support the conversation about how Jake was getting on

at college and demonstrated in a palpable way that he was familiar with the college

environment outside the learning support block,

Jake: Yeah. Performing Arts I could show

you...there are loads of things to show

you...we need the whole day..! If you want to...maybe we should see classrooms

first because there's more classrooms

Researcher: So do you know your way around most of college or just this bit

near here?

Jake: This part really, I mean we went down to the Lowood bit

for the futures fair

that was on which is where you...there were lots of organisations like universities there....

The collage activity and the card sort methods

required some participant reflection and therefore allowed for silences during

the interview involving thinking time or ‘use of pause’ (Lewis 2001), and

the ensuing discussion could then be framed around these visual choices. Jake

was also able to look at the tablet and move things around while we discussed

them,

Researcher: So it's just getting an idea of size so you

can have a fiddle with that

[silence ...32 seconds... while Jake moves

the pictures around]

Jake: I'll put heart maths ....PE is

like there ....[pause while Jake moves the pictures

around]

Researcher: ICT quite big there isn't it?

Jake: Just trying to fit it all in

Researcher: Yeah. [silence...14 seconds... while Jake

continues]

The walking interviews also lent a purpose and

structure to the discussion, whereby we were on a ‘mission’ to take photographs

of the college that resulted in the conversation already having a focus. The

walking interviews took the pressure off the social interaction required and

reduced the need for eye contact and face-to-face talk which some young people

with ASC, including Jake, could find problematic. For example, Jake was able to

respond in some detail to a relatively closed question that might not have been

the case in the intensity of a one-to-one interview,

Researcher: And how are you finding all the work this year? Are you

finding it easy, is it

easier than school? Is it about the same? Is it more difficult?

Jake: Well

I would say it's easier because it's lower quality... but...because last year I was doing

GCSEs, this year it's like entry level...but I am doing functional skills 2 in English which is

equivalent to a C but I would

say it's slightly easier 'cos it's that educational course but...it's

gonna be harder when I do

my next course because that's more mainstream but I think I should cope

well because I know lots of

people

The collage method contained visual symbols

of the main subjects that Jake was likely to be doing at school presented of

equal size and in random order. It was Jake’s task to move them around and

create an arrangement that represented his main interests in some way. This

helped to prompt verbal reactions to certain subjects, and for Jake, to suggest

other subjects or activities that were missing,

Researcher: Oh media, did you say media?

Jake: We have done some media. Not sure

if media's in there [in the choice of

pictures]

Researcher: Shall we add it?

Jake: Yes

Copies of the card sorts and collages that

resulted were emailed to Jake after the interview took place so that he could

have a visual record of what we discussed in the interview. This proved

invaluable at the second round of interviews after a six-month gap as it

addressed some of the issues relating to poor memory (Preece, 2002) by offering

a concrete visual representation and reminder of our conversation. Jake was

able to look back at the collage from the first interview and articulate the

extent to which his interests had changed from the original collage,

Researcher: Do you think anything has changed? Do you think anything has

got bigger or

smaller?

Jake: I'd probably say that's still the case really now

Researcher: Yeah so those are still the things: swimming, IT, science, Maths

are all quite big and

these

Jake: Art,

drama's quite big, English is about medium-sized, media is quite small sized but I'd say

because I do the media um, like a taster in the media, I'd say that has actually, the media has got

bigger

All the methods used within the interviews had

another purpose in helping to readjust the power relationship between the researcher

and participant (Lewis & Porter 2004) by

sharing the process more with the participants themselves. Handing over the tablet

to order the card sorts, to arrange the collage and to take photos all

contributed to this changing relationship to the point where, in the walking

interview, the participant was literally leading the researcher around

unfamiliar territory. The extract below shows Jake leading the way during the

interview and really ‘owning’ the space of his college,

Jake: The

classroom's there and that's T45 and that's also where we do media so I can take it

[takes picture of the media corridor onto which the classrooms open]

Figure 7. Media Corridor Figure 8. Outside media classroom

Researcher: And have you seen where ICT will be next year, have you seen the classroom that will be

in?

Jake: I've

seen...we went into one of the classrooms where I might go for like my interview so if you want to

see where I went, we could go there if you

want? We can go down and I can show you the ICT and the um...my

normal classroom

Limitations

of methods used

One of the dangers of scaffolding the

interviews and using collages and card sorts with pre-determined choices is

that the results can sometimes be too prescriptive, as Brewster explains, in

relation to interviewing people with learning difficulties with little or no

speech,

“A

characteristic many of these methods share is a reliance on pre-selected

vocabulary; but how do you identify the specific vocabulary without ‘putting

words into their mouths’?” (Brewster et al. 2004: 166)

Jake was able to add some choices to his

collage but did not add any extra cards to the card sorting exercise, and this

may have limited the range of considerations regarding the transition to

college.

It could be argued the these methods could

have been used more effectively if more participation had been sought from the

respondents earlier on in the research process.

Jake was articulate and would have been able to contribute to ideas

about his likes and dislikes at school and his anxieties about college that

could have helped to inform the design of the collages and card sorts to help

with other participants (Nind, 2014).

Discussion

The use of tablet applications during the initial

interviews with Jake helped to structure the interview and direct focus away

from social interaction and towards the tasks, perhaps making it more

comfortable for him. This was particularly helpful at this early point in the

research when the researcher was a complete stranger to Jake and was

interviewing him on his own in a room at school. The applications also helped to make

reflections about capabilities and transition more concrete and that helped to

support Jake in conceptualising the future.

The walking interviews in the college environment also

afforded a greater insight into Jake’s experience in the sense of walking with

him in his journey around college and also allowed him to take the lead in

showing the researcher around his territory, rather than just describing it

(Clark and Emmel, 2010). He was, at that

time, in his second term at college and was already looking forward to moving

on to a level two course within the mainstream of college, the researcher was

able to witness the learning support corridor of classrooms in one block of the

college and was then taken to a busier part of college where Jake would be

taught in the following year. It became

clear that it had been a transition year within college from learning support

to mainstream course and a traditional interview in one fixed place would not

have demonstrated this embodied experience of Jake’s on-going transition.

Conclusion

The methods used in this research were

tentative and experimental but attempted to locate the focus of the experience

of transition for the participants with ASC and learning difficulties by

ensuring that they had a range of opportunities to express themselves. The methods

could also be adapted according to the needs and abilities of different

participants, with more use of visual symbols or fewer symbols used to those

with a greater degree of learning difficulty. While it would be an

exaggeration to claim this research to be truly participatory (Nind, 2014), the

concept of the ‘interrupted interview’ does begin to take small steps towards

more inclusive research. Challenging ourselves to think creatively about

traditional qualitative methods will help to put young people with autism and learning

difficulties at the heart of research, and will deepen our understanding as we

walk with them in their journeys.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the young

people, their families and key professionals who took part in this research and

were willing share their thoughts about transition. In particular, the

participants with ASC who spent time trying out my tablet activities, deserve

special thanks and appreciation. Thanks to the ESRC for funding this research.

References

Booth,

T. & W. Booth (1996), 'Sounds of Silence: Narrative research with

inarticulate subjects' Disability &

Society, 11(1), 55–70

Breakey, C. (2006), The Autism Spectrum and Further Education: a Guide to Good Practice,

London: Jessica Kingsley.

Brewster, S.J., L. Therapist and K. Norton (2004),

'Putting words into their mouths ? Interviewing people with learning

disabilities and little/no speech', British

Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32, 166–169

Cameron, L. and J. Murphy (2002), 'Enabling young people with a learning

disability to make choices at a time of transition', British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30 (3), 105–112

Chown, N. and N. Beavan (2012), 'Intellectually

capable but socially excluded ? A review of the literature and research on

students with autism in further education', Journal

of Further and Higher Education, 36 (4), 477–493

Clark, A. and N. Emmel (2010), Realities

Toolkit # 13. Using walking interviews,

NCRM

DfE, BIS, DWP, DoH and Ministry of Justice (2014),

Children and Families Act, London:

HMSO

DfE (2008), Education and Skills Act, London: HMSO

Gubrium, J. and J. Holstein (2002), From the Individual

Interview to the Interview Society in Gubrium J. and J.Holstein (eds), Handbook of Interview Research, London:

Sage, pp.3-33.

Harrington, C. and M. Foster (2013), 'Engaging

young people with Autism Spectrum Disorder in research interviews', British Journal of Learning Disabilities,

42 (2), 153-161

DfE and DoH (2014), Special Educational Needs and Disabilties (SEND) Code of Practice : for

0 to 25 years, London: HMSO

Kanner, L. (1943), 'Autistic disturbances of

affective contact', Nervous Child, 2,

217-250.

Kvale, S. and S. Brinkmann (2009), Interviews, Learning the Craft of

Qualitative Research Interviewing, London: Sage

Lewis, A. (2001), 'Reflections on

interviewing children and young people as a method of inquiry in exploring

their perspectives on integration/inclusion', Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 1: no.

doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2001.00146.x

Lewis, A., H.Newton and S. Vials (2008), 'Realising child

voice: the development of Cue Cards', Support

for Learning, 23(1), 26-31

Lewis, A. and B. Norwich (2005), Special Teaching for Special Children?

Maidenhead: OUP

Lewis, A. and J. Porter (2004), 'Interviewing

children and young people with learning disabilities: guidelines for

researchers and multi-professional practice', British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32(4), 191-197

Milton, D. and R. Mills and L. Pellicano (2012),

'Ethics and autism: where is the autistic voice? ', Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44 (10), 2650-2651

Mitchell, W. (1999), 'Leaving Special School:

The next step and future aspirations', Disability

& Society, 14 (6), 753–770

Nind, M. (2009), 'Conducting qualitative

research with people with learning, communication and other disabilities:

methodological challenges', Available at: http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/491/

Nind, M. and H. Vinha (2013), 'Practical

considerations in doing research inclusively and doing it well : Lessons for

inclusive researchers', NCRM

Methodological Review Paper

Nind, M. (2014), What is inclusive research? London: Bloomsbury

Palikara, O., G. Lindsay and J. Dockrell (2009),

'Voices of young people with a history of specific speech and language

difficulties in the first year of post-16 education', International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 44 (1),

56–78

Preece, D. (2002), 'Consultation with

children with autistic spectrum disorders about their experience of short-term

residential care', British Journal of

Learning Disabilities, 30, 97-104

United Nations, (2008), Convention on the

Rights of Persons with Disabilities

http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml

accessed 10th November 2014

Weiss, R.S. (1994), Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies New York: Simon & Schuster

Wing, L. (1996), The Autistic Spectrum, London: Constable & Robinson