Research

with school students: four

innovative methods used to explore effective teaching

Jessica

Faye Heal, Teach First and the University of Manchester

Abstract

This

article outlines

the need for innovative research methods and discusses four approaches

employed

within an educational setting to enhance how students between the ages

of 5-18

years old engage in research exploring effective teaching. It draws on

upon Article

12 of the

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, focussing on the

'space'

in which the research is conducted and the 'voice' of the child.

Through two

techniques to scaffold the semi-structured interview, a child-led

classroom

tour and a 'draw-and-tell' style method, the

researcher-participant

power imbalance is interrupted. Their efficacy to disrupt lies in the

following

unifying characteristics: providing familiarity to the student,

situating the

student as an expert and giving the student choice.

Keywords: innovative

research methods; young people; education; interviews; draw and tell;

child-led; child rights, primary, secondary, student voice

Introduction

As

a doctoral researcher, ex-language teacher and full time qualitative

researcher

at Teach First, students are at the heart of what I do and the reason I

do what

I do. Since my undergraduate days, I have been passionate about

bringing

unheard voices to the fore, and for the last seven years I have been

working

with young people from the poorest backgrounds that our society

consistently

ill-considers and ignores.

The

opinions and perceptions of these students are of central importance to

how we

recruit, train and support our teachers at Teach First. This article,

adapted

from the Inequality in Education - Innovative conference presentation,

highlights why the student voice is such an important issue and then

outlines

four methods that enhance how students participate in our research.

Although

conducted within an educational setting, these methods are transferable

for use

with children and young people more broadly and the citations and

language reflect

this. Working in compliance with Article 12 of the United Nations

Convention

Rights of a Child, these methods aim to disrupt the

interviewee-interviewer

power balance by providing choice, ownership and familiarity. These

methods are

arguably effective in supporting students to make informed and valuable

contributions to research into effective teaching.

The

project overview

Over

the past year, interviews have been conducted with 124 students, 21

teachers

and 20 mentors in order to explore what appears to be making their

classroom a

successful learning environment. The teachers are purposively sampled

through a

combination of data and recommendations from those who work closely

with them.

They, in turn, then put forward a selection of higher, middle and lower

attaining pupils for us to work with. After data collection, a thematic

analysis is conducted and the findings from this inform how we recruit,

train

and support new teachers.

However,

there is a tension in using the word ‘effective’

– this positivist term sits

quite uneasily within our qualitative, more intepretivist research.

This is a

product of our industry, conducting researching within a sector where

‘impact’,

and the measurement of it, accounts for substantial funding income.

Within this

institutional imperative, we aim to craft a space within which valuable

qualitative research can be carried out. This is through the loose

interpretation of the word ‘effective’ to mean

‘standing out as a teacher that

the education community is able to learn from’. To explore

which elements of

teacher practice should be learnt from, it is paramount to seek to

understand

what students feel they most benefit from – they are the ones

currently

experiencing a variety of different classrooms and are therefore most

attuned

to how they learn.

Why

we need different research methods

The

UNCRC Article 12 states all young people have the right to be heard,

and that

their voice must be given ‘due weight’ in matters

which concern them. This

contributes to this paradigm shift in research design in social

science, moving

from merely respecting participants to a considered, contextual and

culturally

sensitive approach (Suinn, 2006). In line with this development, the

academic

community has an ethical obligation to uphold this paradigm when

conducting

research with students.

Designing

research which works within the principles of article 12 has been

explored in

depth by Lundy who posits that you need to go beyond the stated

requirements in

order to fulfil them, ensuring students:

- Can express

their voice through

whichever medium they prefer

- Have a safe and

inclusive space to

form and express a view

- Have an

audience that will listen to

the view

- Hold views

which will be of

influence and acted upon

(2007;

2013: 2)

It is our responsibility to create an environment to ensure students feel empowered: conducting research with students, not about them (Thompson, 2009). This comes from the premise that 'we desire to position children as social actors who are subjects, rather than objects of inquiry' (Christensen and James, 2008: 2). The work of the researcher can be compared to work of a gallery curator — it is the students who are the masters and experts of their situation and the role of the researcher is to ensure the gallery doors are open and it is teeming with an audience who leave affected. This is where the four methods come in, facilitating the creation of these oeuvres.

Four

approaches to support student voice

The

methods below focus on supporting the ‘voice’ and

‘space’ elements of Lundy’s

Article 12 framework (2013). Methods one and three scaffold the

traditional

semi-structured interview through a pre-task and using student work as

a

prompt, method two is an exploratory child-led tour of the classroom

and the

last is a creative research method. Looking beneath the surface of each

method,

they share the following qualities:

-providing

students choice

-enabling student

ownership

-structuring the

interactions within familiarity

-disrupting the

interviewer-interviewee power balance

Redressing

the power balance in an interview situation is a key issue when

conducting

qualitative research because the power

relations that emerge in interviews are embedded

within the data they produce (Briggs, 2003). With young people and

vulnerable

groups, this is an even greater issue because the imbalance between

interviewer-interviewee is exacerbated (Morrow

and Richards, 1996, Edger and Fingerson, 1999). Lincoln

and Guba (1985), Denzin and Lincoln (2000) and

Flick (2002) all highlight the need for researchers to be vigilant to

ensure

that the participants feel comfortable to speak in a voice that is

authentic.

Logistically,

interviewing students generally takes place in pairs. This not only

acts as a

physical shift in the power ratio, 2 interviewees: 1 interviewer, but

also

reduces participant discomfort and helps them to build on ideas as a

pair. This

has been shown to create an environment where participants are more

animated and

give more substantiated, nuanced and comprehensive answers (Lohm

and

Kirpitchenko 2014).

Pre-interview

tasks

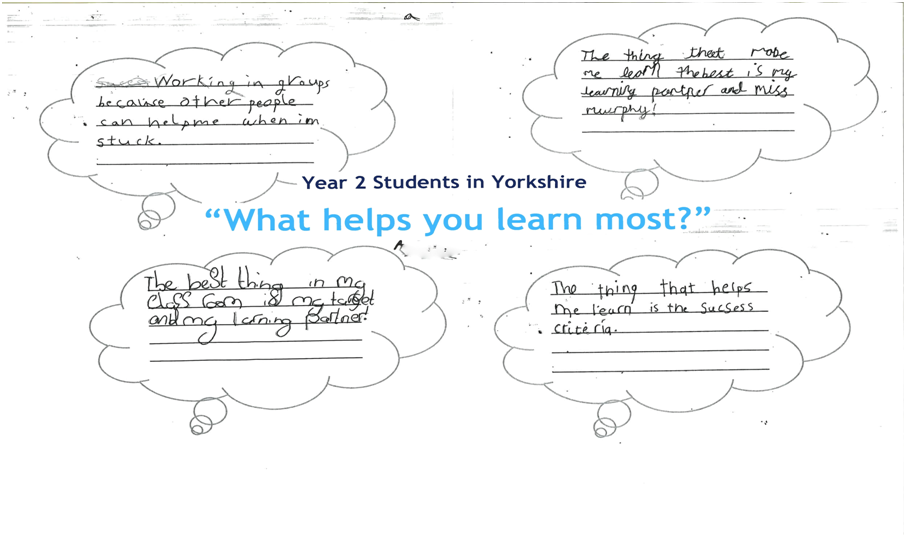

Figure

i: Four examples of student

learning bubbles

The

day before the visit, a Year 2 Class in Yorkshire (ages 6-7) were asked

to fill

in a learning bubble, answering the question ‘what helps you

learn most?’.

Learning bubbles were a familiar classroom tool, which the teacher used

regularly to help the students reflect on their learning; this meant it

was a medium

of communication they already knew how to engage with. It should be

noted that

with any regular classroom activity considering ‘school

genres’, implicit rules

and regulations could be acting upon the students’ engagement

in the activity

(Moss, 1989).

The

students’ responses were collated and used to inform the

research in two ways.

Firstly, they supported the group interview as using pedagogic language

familiar to the students mitigated issues highlighted by Sarah Punch;

when

adults and children use a vocabulary or language style which is

unfamiliar to

the other (2002). This communal understanding of language allows both

the

interviewer and students to access the conversation. For instance, the

extract

below shows students explaining a particular concept they had

referenced on

their learning bubble.

JFH:

Okay, so one thing it says here is that your learning partner helps you

learn.

What is a learning partner?

Trey:

It’s a partner that helps you learn. If you’re

stuck on anything, you can’t do

it by yourself, then you have to go with a partner.

Jenny:

They help you a lot.

Leyla:

If you’re stuck, you ask your learning partner, and if your

learning partner is

stuck with you asking a question, you ask the teacher instead.

Trey:

Everyone’s in it together, you’re not by yourself.

This

interview extract shows the underlying feelings students have around

their

class ethos and the sense of security it affords. This method gives

students

time to prepare, is sensitive to their experience and empowers them to

talk

about the situation (Gallagher, 2008). Fundamentally, it gives them

ownership

of the discussion by building on their previous learning bubble

answers. A

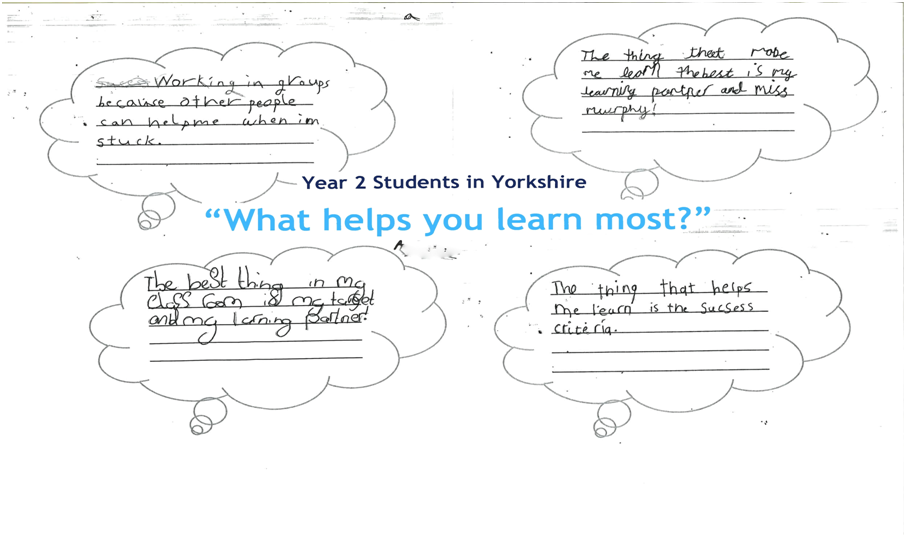

secondary benefit of the pre-interview task is that it enables the

collation of

answers from the whole class, providing a broader snapshot of how the

class

feels about their learning. It’s striking that two thirds of

the class, in this

example, gave an answer which was not their teacher; suggesting that

certain

pedagogical strategies could help to build student independence.

Figure

ii: Whole class response to the

question ‘what helps you learn most?’

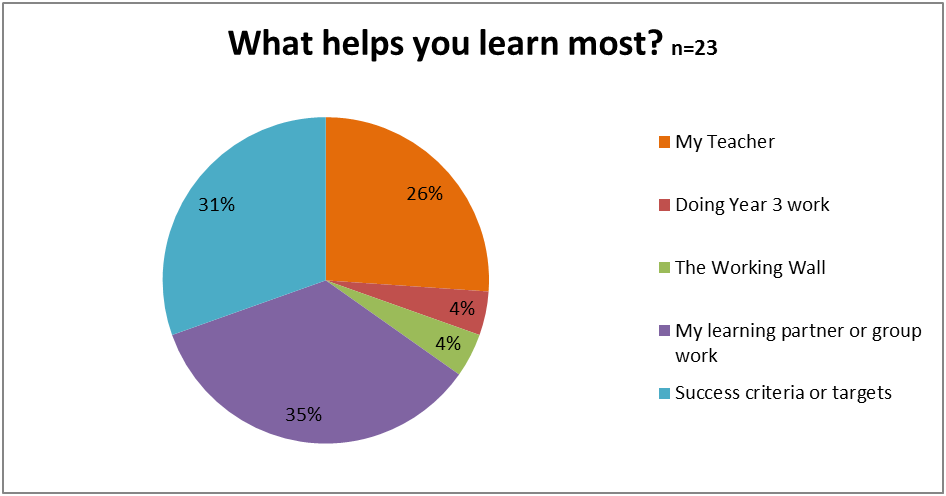

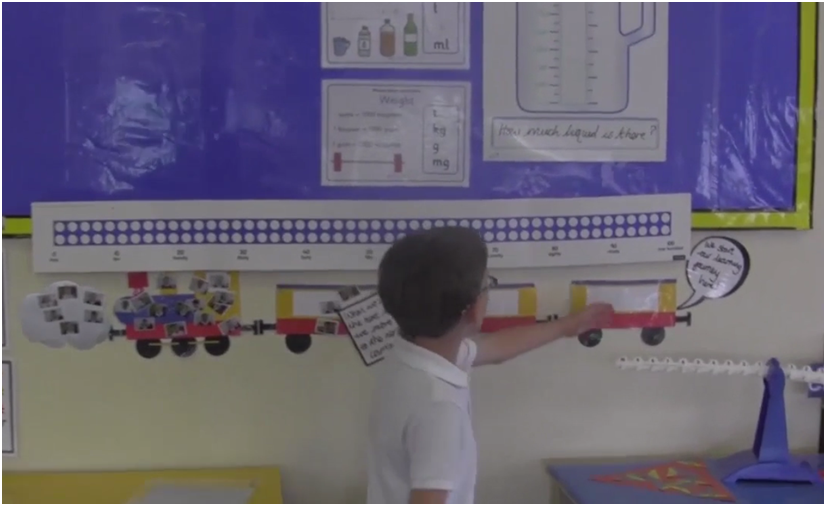

Classroom

Environment

‘The

use of child led tours privileges the ways that young children

communicate, in

active, visual ways’ (Clark, 2010: 117).

A

student from the same Year 2 class conducted a tour of his classroom,

the

researcher then films the classroom displays that helped the student

learn

most: the ‘progress train’ on the display board

[figure iii] and his target

stuck onto his table [figure iv]. The student had ownership over the

data

collected, an expert within a familiar environment who had the choice

of where

to go and what to discuss. The tour was fully child-led and, although

Trey was

not operating the camera himself, he directed where it should be

pointed. This

approach opens up a new communicative space which provides a window

into the

classroom through the eyes of a student. This child-led approach

reveals a new

angle for teachers and educationalists to understand how students

perceive and

value their environment (Clark, 2010: 122).

Figure

iii: Screen shot of the

‘progress train’ which Trey wanted to show me

because it helps him learn if he

knows where he is on the train.

Figure

iv: Screen shot from filmed

class tour, this image shows Trey discussing his target and how he

finds it

useful as a reminder of what to focus on

The

classroom tour, pre-interview task and semi-structured interview

combined with

classroom footage of teaching and learning, is reminiscent of the

multi-method

Mosaic Approach developed by Clark and Moss (2004). The

multi-faceted method is designed to help adult

researchers who wish to listen to young children's perspectives by

capitalising

upon young children's competencies (Kay, 2009). It enables a broader

and deeper

picture of the classroom to be drawn, giving us multiple materials to

both

analyse and then share with those who can learn and act upon it.

Student

work

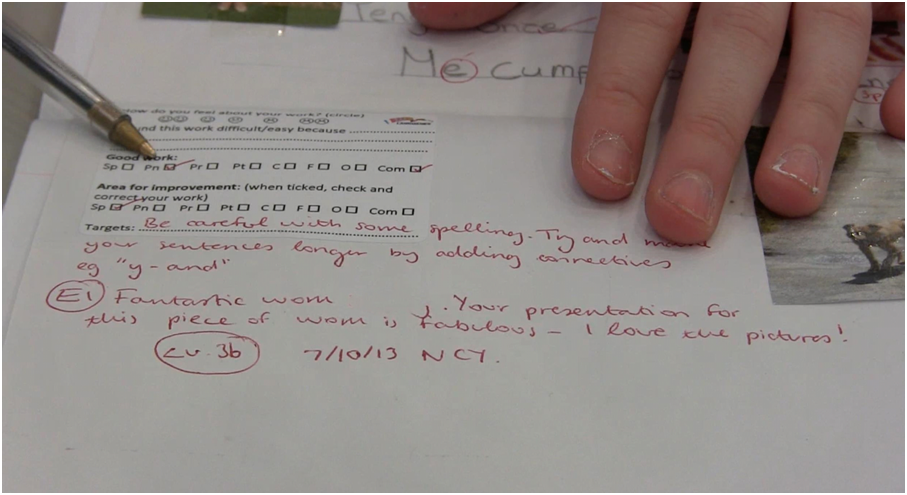

School

work has be found to be a useful prompt for secondary school age

students

during the semi-structured interview. The use of student work developed

the

interview into a more exploratory conversation through revealing deeper

reflections, perceptions and subjective understandings of student experience. The example below,

featuring two Year 7

students (ages 11-12) discussing how their teacher marks their books,

highlights how it can ‘uncover unarticulated informant

knowledge’ (Johnson and

Weller, 2001: 491).

Amy: She gives us

comments and because on mine, I spelt something wrong

and I didn’t do all of the accents on the tops of the words,

she will write

comments like, be careful with spellings and try and make your

sentences longer

and don’t forget your accents. She will give you

levels…She will give you bit

to fill in…You have to do how you felt about your work like

circle them and

explain how you felt. Then Miss put I did good work and she

didn’t put spelling

that much she just put punctuation because I miss a lot of the accents

out.

Ben: ...Once

we know what we are struggling on we can improve it and

that we need to improve on that and that helps us get our work to be

almost

perfect.

JFH:

That is really interesting,

because you enjoy the fun stuff but that is not a fun thing but like

you said

it helps you. Can you explain that in a way that? What could a new

teacher

learn from that?

Ben:

Try to use comment much as

you can because if someone in your class is struggling…

Ben:

…Also it helps because say

that someone is struggling in class and they don’t want to

speak out loud to

the teacher, they can write it down like a small message. Once the

teacher has

got it they can think – they will look everyone is work and

if most people put

the same thing she has then got like a lesson plan that we can do.

Figure

v: Screen shot from interview

of students discussing how their work is marked by the teacher

The

conversation veers into

deeper personal reflections, such as how they improve and how the

teacher has

reduced the discomfort caused by asking for help within the classroom

setting.

This

method,

although logistically different, acts in a similar way to the

pre-interview

task approach. It acts to redistribute the power balance between

interviewer

and interviewee by centering the conversation on an item that is

familiar to

the students and related to their personal experience, which enables

them to

confidently be experts. These methods, however, rely on a key factor:

students

feeling comfortable enough to overcome the power imbalance of talking

to a

relative stranger and, in some cases, on camera.

This

last section will move onto discuss a method employed to be

inclusive of those who are keen to express themselves through a

different

medium.

Draw

and tell

Alongside

other creative methods, draw and tell was developed in order to

maximise

student participation in research by offering an alternative to

traditional

data collection instruments. Emerging in an early form as 'draw and

write' in

the health research field in 1972, it was noted six and seven year olds

were

able to better draw their feelings and emotions, than articulate them

(Wetton,

1999).

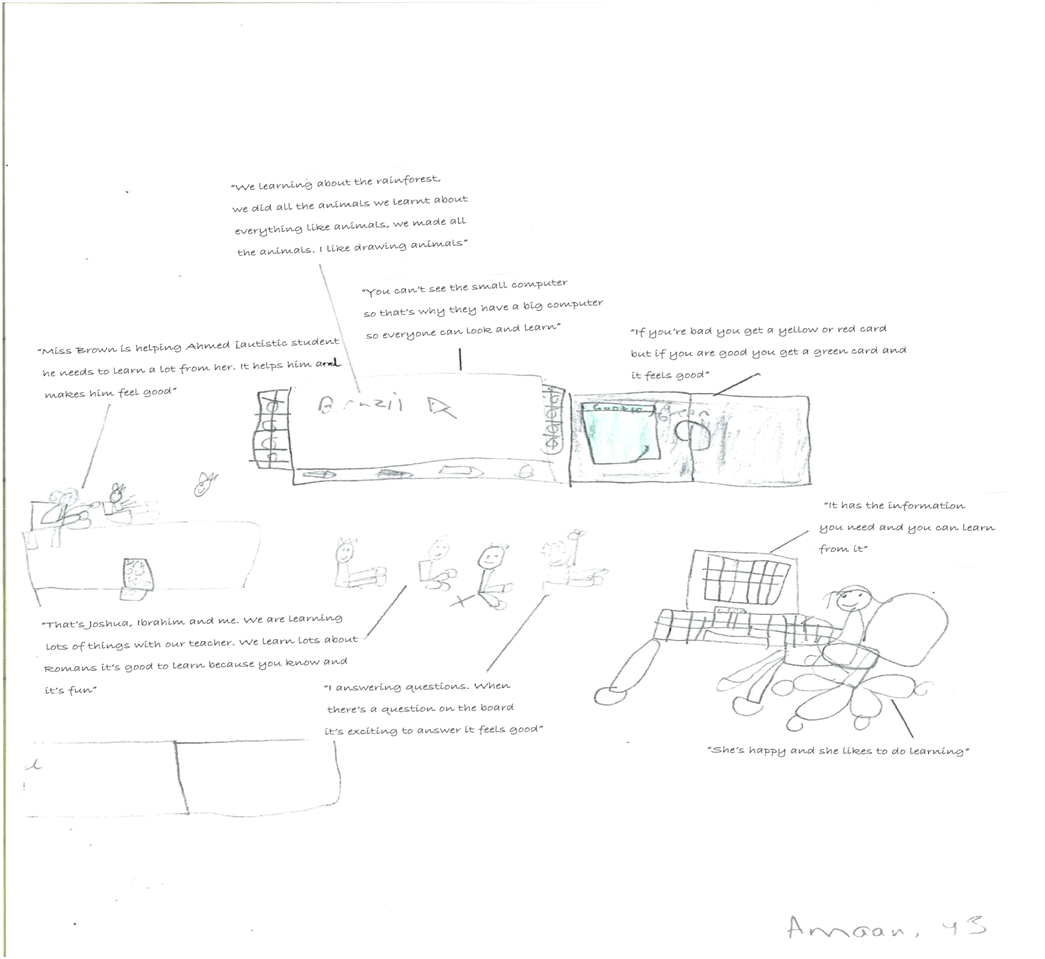

The

draw and tell method has been employed with Primary students who do not

feel

comfortable talking with us. These pictures below are snapshots from a

drawing

created by Amaan, a Year 3 (ages 7-8) student from Birmingham, who was

sat on

the lower attaining table. Amaan was very shy and uncommunicative so I

asked if

he could draw a picture of his classroom and what he likes about it.

Once he

began drawing, I then asked 'can you explain this to me?' about each

part of

his picture as he drew, noting down his account verbatim. I then

annotated his

drawing with his explanations.

Figure

vi: Year 3 Student draws their

class and explains each picture

This

method is particularly effective in allowing students to take time to

think,

building their answer in stages rather than needing to provide an

immediate

response (Gauntlett, 2004). As Angell stated, this approach goes some

way to

equalising the ‘power imbalances’ between adult

researchers and children: as it

offers ‘each child an opportunity to subtly negotiate their

own level of

participation’ (2014: 10).

Conclusion

‘We

tried to make the children experts in their own

lives, and to inform them that this was the case. Many of the children

were

clearly unused to being regarded as the most important sources of

information

about their own lives in this way- certainly by an adult they hardly

knew’

(Langsted 1994: 35)

It is

within these drawings, interviews and tours that I hope our research

goes

beyond Article 12 in providing the opportunity for all students

– irrespective

of any measure or label – to influence their experience and

the experience of

other students across the UK.

The

data we create with students has become more nuanced and powerful in

its

ability to influence through having the following qualities:

-providing

students choice

-enabling student

ownership

-structuring it

within familiarity

-disrupting the

interviewer-interviewee power balance

Whatever

shape the method takes, if it considers these elements it can make a

valid

contribution to the students, the researcher and the organisation it

aims to

influence. Using these methods

has provided accessible

and realistic representations of student experience and has been used

in

analysis to enhance how teachers understand students and what they

perceived as

important. It brings the classroom to the organisation in such a

measure that

traditional interview copy cannot compete.

The

four methods outlined aim to be a tool for researchers to scaffold

their

approach to support and situate students as the experts of their

situation. The

more students are empowered, the better the data and therefore the

easier it

becomes for this voice to influence policy and strategy. And, just like

the

classroom pedagogy, the more time you invest in thinking about the

students you

want to work with, the more they will invest in you.

Acknowledgments

Thank

you to Teach First and the University of Manchester for advice and

support and

to all the students and teachers who welcomed me into their classrooms.

Lastly I’m

grateful to Siobhan Dytham and Carli Rowell for organising such an

interesting

conference and giving me the opportunity to present.

List

of Illustrations and Graphs

i.

Student

Learning Bubbles

ii.

Pie

chart of ‘What helps you learn most?’

iii.

Screen

shot from video of classroom tour

iv.

Screen

shot from video of classroom tour

v.

Screen

shot of student work

vi.

Drawing

from interview ‘what’s your class like?’

References

Angell,

C., Alexander, J., and Hunt, J. A. (2014), ‘Draw, write and

tell’: A literature

review and methodological development on the ‘draw and

write’ research method, Journal

of Early Childhood Research, August, 1-12

Briggs,

C. (2003), ‘Interviewing, Power/Knowledge and Social

Inequality’ in Jaber F.

Gubrium, and James A. Holstein (eds), Postmodern Interviewing,

Thousand

Oaks: Sage, pp. 242-55

Christensen,

P., & James, A. (Eds.). (2008). Research

with children: Perspectives and practices. Abingdon:

Routledge.

Clark,

A. (2004), ‘The Mosaic Approach and Research with Young

Children’, in Lewis.

V., Kellett, M., Robinson, C., Fraser, S., and S. Ding (Eds), The

Reality of

Research with Children and Young People. London: Open

University pp.

142-161

Clark,

A. (2010), ‘Young children as protagonists and the role of

participatory,

visual methods in engaging multiple perspectives’, American

Journal of

Community Psychology, 46(1-2), 115-123

Denzin,

N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S., (2000), Handbook of Qualitative

Research, 2nd Edition.

London: Sage.

Flick,

U. (2002), An Introduction to Qualitative Research,

London: Sage.

Gallagher,

M,, (2008), ‘Data Collection and Analysis’ in Tisdall,

K., Davis, J. M., and Gallagher,

M. (eds). Researching with children and young people:

Research design,

methods and analysis, London: Sage, pp. 65-77

Gauntlett

D., (2004) Using new creative visual research methods to understand the

place

of popular media in people’s lives. Paper presented at the

IAMCR, Porto Alegre,

Brazil, 25–30 July, 2004

Johnson,

J, and Weller, S., (2001), ‘24 Elicitation Techniques for

Interviewing’, in

Jaber F. Gubrium, and James A. Holstein (eds), Handbook of

Interview

Research, Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 491-515,

Kay,

E., Tisdall, M., Davis, J.M., and

Gallagher, M (2009), ‘Glossary of Terms’, Researching

with children and young

people: Research design, methods and analysis,

London: Sage, pp.

223-31

Langsted,

O., (1994). ‘Looking at quality from the child’s

perspective’, In Moss, P.,

& Pence, A., (Eds.), Valuing quality in early

childhood services: New

approaches to defining quality (pp. 28–42). London:

Paul Chapman.

Lincoln,

Y.S. Guba, E.G., (1985), Naturalistic Enquiry.

London: Sage.

Lohm,

D. and Kirpitchenko, L. (2014), ‘Interviewing Pairs:

Discussions on Migration

and Identity’, in

Research

Methods Cases, London: Sage

Lundy,

L., (2007), ‘Voice is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12

of the United

Nations Convention the Rights of the Child’, British

Educational Research

Journal, 33(6): 927–942

Lundy,

L and Welty, E., (2013), ‘A children’s rights-based

approach to involving

children in decision making’, Journal of Science

Communication, 12(03),

pp. 1-5

Moss,

G., (1989), Un/Popular Fictions. London: Virago.

Morrow,

V., and Richards, M., (1996), ‘The ethics of social research

with children: an

overview’, Children & Society 10:

90–105.

Punch,

S. (2002), ‘Research with children: The

same or different from research with adults?’. Childhood, 9(3),

321-341.

Suinn,

R., (2006), 'Preface', in Trimble, J.E., and Fisher, C.,B (Eds.) The Handbook of Ethical

Research with Ethnocultural

Populations & Communities, Thousand

Islands: Sage.

Thomson,

P. (Ed.).

(2009), Doing visual research with children and young

people. London:

Routledge.

United

Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, (2009), General Comment

no. 12,

The Right of the Child to be Heard (CRC/C/GC/12), http://www.refworld.org/docid/4ae562c52.html, accessed

17/10/14

Wetton, N.

(1999), Draw and Write.

Health Education Unit. Southampton: University of Southampton.