Teaching Synaesthesia as a

Gateway to Creativity

Monica D. Murgia

Abstract

This article encapsulates my

experience of teaching creativity within a higher education curriculum.

Creativity often eludes common understanding because it involves using

different conceptual streams of thought, often times developing unconsciously

and manifesting in the prized “eureka” moment. In 2009, I began explaining the neurological

condition of synaesthesia and later introduced this phenomenology in a course

designed to cultivate creativity to first year fashion design students. There are many challenges in

teaching creativity. Through teaching this course, I discovered that the first

challenge is making the students conscious of their own qualitative beliefs on

creativity and art. The second is creating exercises to challenge and alter

these beliefs, thus forming a new way of thinking and experiencing the world. The

most resistance from my students arose when experimenting with

non-representational art. They did not have a conscious framework for making

and evaluating abstract art. Introducing synaesthesia, a neurologically-based

condition that “merges” two or more sensory pathways in the brain, gave my

students a framework for discovery. Understanding sensory modalities and ways

in which these modalities can blended together in synaesthesia proved to be a

gateway to creativity in many of my students. The scope of this article

chronicles how I developed my teaching methodology, the results it created in

my classroom, as well as its effects on my own artistic practice.

Keywords: synaesthesia;

creativity; arts practice; teaching; cross-modal

Introduction

The

great enigma in fashion and art lies around creativity: Where does it come

from? Is it innate in some people, and

missing in others? Is it something that can be fostered, and if so, how? I am a

firm believer that creativity, however elusive and indefinable, is something

that can be taught. In fact, there are many things that have to be “unlearned”

to allow creativity to grow. The visual experience is whitewashed with

memories, thoughts, and ideas of what should be present, instead of what is

actually there.

In The

Creative Mind: Myths and Mechanisms, Margaret A. Boden shares a similar

view. She explains that creativity is rooted in everyday abilities such as

conceptual thinking, perception, and memory. Therefore, to some degree everyone

is creative. Boden explains that there are three different types of creativity:

the first involves making unfamiliar combination of familiar ideas; the second

is exploration of conceptual spaces; and the third is transformation of

conceptual spaces (Boden, 2004: 3-4). What makes some people more creative,

then, is their ability to explore and transform their own ideas and mental

processes.

In

2010, I began teaching a college course, entitled Fashion Seminar. This

course was for first year fashion design students, and aimed to help them

develop an identity as a designer and stimulate creativity within the design

discipline. A large component of the class involved developing an art

portfolio. The portfolio was comprised of exercises that encouraged the student

develop creative and abstract thinking skills. Each student was required to

select a natural and manmade image as inspiration. The goal of each weekly

portfolio assignment was to challenge the students to see these images in new

ways. By repeatedly looking at the same images, the portfolio exercises

challenged the students to take something familiar and examine it different

exercises, perspectives, and reinterpret it with various media. Each week, an

assignment was presented to challenge the students to adjust their visual

perceptions in order to encourage their creativity.

I

taught this course for a year and a half, with as many as 5 separate sections

of the same course in a term. Over a number of terms of teaching this course,

the most successful assignment, in terms of the creative output it generated, was

called “multiple sensory”. As the title suggests, the student has to take an

inspirational image and create a visual representation of a multi-sensory experience

evoked by that image. The learning outcome was aimed at encouraging the

students to experiment with nonrepresentational, or abstract, art. In abstract

art, the selection of media and colour combinations is more important than a

recognizable image. This type of art creates a visceral reaction within the

viewer. Many of my students had no previous experience creating abstract art,

so this exercise served as a gateway to experiment with it. To properly

communicate the idea of representing multi-sensory experience, I developed a

curriculum that included case studies from neuroscience. In particular, I

discussed the phenomenon of synaesthesia, a neurological condition, to help

students develop new methods of creating art. Introducing and describing synaesthsia

in the classroom gave the students a structure for experimenting with abstract

art. Over time, they formed new was for observing, creating, and evaluating

non-representational forms For example,

one student, ‘Monet B’, took the inspirational image of a woman smoking. ‘Monet

B’ then created a series of small paintings that expressed a visual

representation of the smell and taste of smoking.

Phenomenology of Synaesthesia

Synaesthesia is a neurologically-based condition in which stimulation of

one sensory pathway (e.g. visual pathway) leads to automatic, involuntary

experiences in a second sensory pathway (e.g. aural pathway). This means that two or more senses merge

together instead of remaining separate. For instance, some synaesthetes—those

that have synaesthesia— will see colours when they hear sound or touch objects.

Every

case of synaesthesia is different. Some people see colours while tasting food. Others

hear sounds from the smell of fragrances. Some can taste sounds and images. There

are more than 100 different types of synaesthesia. The most commonly reported

phenomenon is coloured hearing, that is, sounds producing a visual

manifestation. Seeing letters or numbers in colours is also widely reported. Each

letter or number has a corresponding colour.

The

early researchers of synaesthesia were Heinrich Kluver (1897-1979) and Georg

Anschutz (1886-1953), both of whom worked independently. Frustrated by

romanticized, poetic, and vague descriptions of what synaesthetes were

experiencing, they conducted rigorous studies with the collaboration of synaesthetes

to peer inside their minds, and produce a classification of the experience.

These studies included asking the synaesthetes to create works of art as a way

of capturing their subjective experience.

Synaesthesia

became a romantic ideal in literature, but was widely regarded as an imaginary

condition, or a drug-induced hallucination. However, the advent of modern

medicine affirmed that synaesthesia is a real neurological condition. Dr.

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and Dr. Edward M. Hubbard have pioneered research and

education on synaesthesia, demonstrating through their clinical experiments

that synaesthetes experience a cross wiring of different sensory-processing

regions in the brain (Ramachandran and Hubbard, 2003: 54). In fact, they have

produced evidence of this cross wiring of the sensory pathways in the colourblind:

'We also observed one case in which we believe cross activation enables a colourblind

synaesthete to see numbers tinged with hues he otherwise cannot perceive; charmingly,

he refers to these as "Martian colours"' (Ramachandran and

Hubbard, 2003: 57).

It

is difficult to say how many people have synaesthesia. First of all, those that

experience this blending of the senses since birth do not see it as a

“condition”. This is their regular way of living. Therefore, synaesthetes do

not understand that other people have different sensory experiences. Secondly,

while research has been conducted on synaesthesia since the 1880s, findings

have not been widely distributed. It has been estimated that as many as 1 per

every 100 people experiences synaesthesia. After one of my workshops, a student

approached me and said that he experienced the exact phenomenon I explained. Sean

let me briefly interview him. The full recording is available here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U54FYiTR2pI,

in which he explains:

“When I hear music it’s like an instant graphic. . . . I thought it

was normal. Music is a constant inspiration for me, because it’s like an

instant installation in my mind.”

To

a certain degree, everyone experiences synaesthesia; Stroop interference tests

are perfect illustrations (De Young, 2014). Stroop interference tests use the

words to describe a colour but are written in a different coloured ink. For

example, the word blue is printed in red ink. You are asked to identify the

word, and ignore the colour – which after a succession of coloured words

becomes tricky to instantaneously identify the word. The mind starts to

associate more quickly with the colour of the text, instead of the meaning of

the text. According to a scientific study, synaesthesia is seven times more

common in creative people than in the general population (Ramachandran and

Hubbard, 2003: 57).

Teaching

Methodology – Synaesthesia in the Classroom

During

my research of the various types of synaesthesia, I discovered that they each

contained a common thread. Synaesthesia allows the individual to make arbitrary

links between seemingly unrelated visceral stimuli. This ability to

successfully link apparently unrelated ideas and concepts is the first of

Boden’s creative triad.

To

access exploratory and transformative creativity, Boden explains that one must

have a structure. Creativity is “not a matter of abandoning all the rules, but

of changing the existing rules to create a new conceptual space. Constraints on

thinking do not merely constrain, but also make certain thoughts - certain

mental structures - possible” (Boden, 2004: 58). Synaesthesia became the

structure and conceptual space for this particular assignment. In addition to

explaining the neurological phenomenon of synaesthesia, I showed examples of

relevant artwork to my students to demonstrate the creative potential of the synaesthetic

experience. Through my own research, I found evidence of many painters that

exhibited synaesthetic characteristics. For instance, the exhibition catalog

for the show Synaesthesia: Art and the Mind, a show produced by McMaster

Museum of Art, examined the work of legendary synaesthete artists, including Vincent

Van Gogh, Wassily Kandinsky, Charles Burchfield, Joan Mitchell, and Duke

Ellington.Beyond the subject matter, all of the art by the

aforementioned painters includes unusual colour combinations, rhythmic use of

lines and shapes, and parts of the composition enveloped in auras of colour. These

are typical signatures of a synaesthetic artist.

In

my teaching, I was careful to select vivid and impactful works of art, and

describe their compositions. I would ask the students to look at the art

carefully. What other visceral reactions were induced in the scribbles,

scratches, and drips of paint in front of them?

Slowly, they started to make the association between visual imagery and

other sensory reactions. Perhaps that dripping red paint on one of Joan

Mitchell’s canvases was the murky sense of walking through a puddle. Or the

feel of a spring breeze was the yellow aura in a Charles Burchfield landscape. By

explaining the phenomenology of synaestheisa and explaining works of art that

were created by synaesthetes, the students were able to access a new well of

creativity. After my lecture, I encouraged the students to immediately take

this framework of synaesthesia and apply it to the multiple sensory exercise. Based

on the original images they selected, I asked them a series of questions: How does the image make you feel? Do you feel this sensation or

emotion in a particular part of your body? What memories surfaced from

looking at the images? If you could make a soundtrack based on your

image, what would it sound like? What type of media best represents your

image? I stressed that any type of media was

acceptable for the assignment – drawing, painting, collage – as long as it

expressed this cross-modal experience. They now felt that their assignments

were to capture an ineffable, subjective sense of experience. The assignment

has given a structure for exploration and transformation of their minds. The

students continued working on this assignment for another week before a class

critique.

Measurable

Results – How Did The Students Respond? What Types of Work Did They Produce?

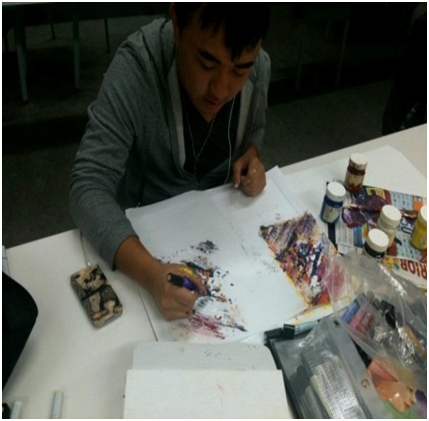

After

introducing synaesthesia and various case studies surrounding it, I found that

students’ creativity was intensely heightened. It allowed the students to

access other sensory experiences for inspiration. Along with the artist case

studies and their own sensory perceptions, students started to experiment with

various media to create art. Understanding the cross-modal experience of synaesthesia

gave each student a greater conscious perception of their own experiences of

the world around them.

The

critiques we held in the class meetings following the assignment were always

interesting. Students, often timid to speak in front of groups, could easily

talk for 10 minutes trying to explain the sensation of watching a sunset, and

trying to capture that sensation on paper. Others felt complete and total

freedom in creating nonrepresentational art. They were creating art that

expressed an experience, emotion, or sensory perception and not merely

replicating the likeness of an object. For many, this was the first time they

felt inspired to create this type of art. They felt enabled to experiment with

various media, including: watercolour, gauche, acrylic, markers, and pencils. The

most popular, consistent media used in this assignment was paint.

The

artwork was compelling, and evocative of other sensory perceptions. During the

critiques, the presenters would beam with pride as the audience would shout out

what sense the artwork was communicating. It became a rather fun guessing game,

which furthered into a dialog of subjective and objective experiencing of the

external world. As Boden suggested, introducing synaesthesia as a structure

allowed new thoughts and mental processes to develop in the students’ minds.

How

Teaching this Methodology has Impacted my Own Creative Process

I

have been a painter for years, and noticed an impact on my work after exploring

synaesthesia as a gateway to creativity. First, I moved more toward abstraction.

I started experimenting with various types of paints and carrier oils. Using

unfamiliar media allowed me to let go of the expectation of what I should paint.

Every time I approached my canvas became a big experiment. I learned to allocate time to paint, and

experiment with the media to let the imagery emerge on its own. As a painter,

it is difficult to express to another person that moment when you know the work

is finished. However, I started to realize when my paintings where finished

when they evoked a certain sensory perception or memory.[1]

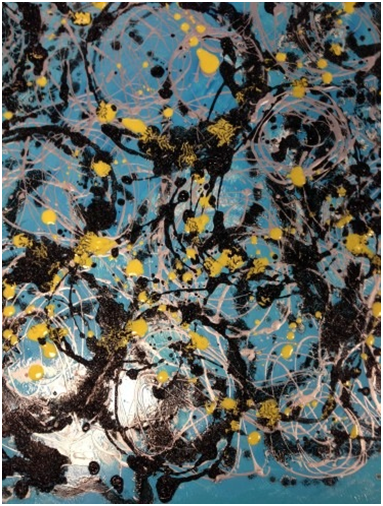

For

example, the image below is a detail of a recent painting I made. It is a

cross-modal representation of raindrops dripping on a puddle. The dark circles

are the visual phenomenon of the rain falling on the puddle, while the silver

paint is the soft sound of the water making contact with the ground. The

painting thus merges the visual field with the aural and perceptual fields of

experience.

Through

my own artistic practice and my teaching, I have shown that understanding the

phenomenology of synaesthesia can lead to a heightened sense of creativity. It

expands the awareness of the individual’s sensory perception of the world and

it becomes easier to experience the external world holistically. Synaesthesia

illustrates a new structure for making arbitrary links between unrelated

visceral stimuli. It also allows the non-synaesthetic artist to abandon the

traditional narrow scope of what art should be. Creating art thus becomes a

spontaneous interpretation of the senses to illustrate the subjective

experience of life.

References

Boden,

Margaret A. (2004) The Creative Mind: Myths and Mechanisms. (New York:

Routledge)

De

Young, R. (2014). Using the Stroop effect to test our capacity to direct

attention: A tool for navigating urgent transitions. Retrieved from http://www.snre.umich.edu/eplab/demos/st0/stroopdesc.html

Ramachandran,

V.S. and Edward M. Hubbard (2003) 'Hearing Colours, Tasting Shapes,' The Scientific American, May 2003.

[1] For more on my personal reflections of creating art, please visit: http://monicadmurgia.com/category/ineffable/