Palestinian Refugees: A

Gendered Perspective

Nof Nasser Eddin*

Centre

for Transnational Development and Collaboration, London, UK

*Correspondence:

n.nasser-eddin@ctdg.org

Abstract This article argues that the situation

of Palestinian refugees is still relevant till this day. There are around five

million refugees living in neighbouring Arab countries, such as Lebanon,

Jordan, Syria and Egypt, as well as neighbouring areas in Palestine itself,

like the West Bank and Gaza Strip, under very precarious conditions. Their

situation is extremely unstable as any changes in the region can influence them

directly.

This article is based on a feminist journey drawing on research

interviews with female Palestinian refugees in camps in Jordan, and with Syrian

Palestinian women in Turkey, Jordan and Europe.

Keywords: Palestine; women refugees;

feminism; feminist methodology; Zionism; Palestinian refugee camps

Introduction

Over the past two years, the issue of

Palestinian refugees has come centre stage following the Syrian crisis, which

resulted in the siege of al-Yarmouk refugee camp in Syria, which began in

December 2012. The issue of Palestinian refugees in Syria is highlighted by the

intensification of events in Syria since March 2011, which poses an increased

threat to the lives of Palestinian refugees living in camps within these

borders.

In this article, I will argue firstly

that the issue of Palestinian refugees is still relevant today, despite the

fact that sixty-seven years have passed since their expulsion from their

homeland, known today as Israel. As Shiblak

(1996) argues, Palestinian refugees

are the largest single refugee group that has been left in limbo for almost

sixty-seven years. The need to address this issue is particularly important

because Palestinian refugees (as well as internally displaced Palestinians)

have been both historically and politically marginalised.

Secondly, I will argue for a need to

gender the debate around the Palestinian refugees, because the distinct

experience of women Palestinian refugees has been overlooked within this

context. Most literature has focused on the Palestinian refugees as a holistic

population, which assumes all refugees share the same struggle. However,

understanding the position of women refugees and the unique struggles they continue

to face is essential to understanding their particular experiences as refugees

and in highlighting their differential needs; this is why a feminist

perspective is needed within the field of refugee studies.

This article is based on a feminist

journey conducted across different times and spaces. It is based on research

interviews with women Palestinian refugees in camps in Jordan, and interviews

with Syrian Palestinian women in Turkey, Jordan and Europe. It also utilises

secondary data gathered about the overall situation of Palestinian refugees

across different host countries. Part of the research data was gathered during my

PhD fieldwork[1]

and another part has been carried out for research conducted by the Centre for

Transnational Development and Collaboration.[2]

Utilising a feminist approach to understand the experiences of refugees is

important for both epistemological and methodological reasons.

Epistemologically, I look at women’s experiences as a valid source of

knowledge, in addition to looking at the participants as constructors of their

‘own realities’ rather than passive ‘objects’ under study (Reinharz, 1992). Moreover, Palestinian women refugees in particular

have been marginalised from academic debate, and a feminist perspective will

give this marginalised group a voice. In likeness to feminist theory and

methodology, it is important to acknowledge the intersectionality of systems of

oppression to understand experiences differently.

Historical Background

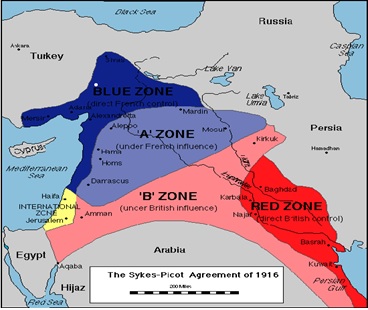

Whereas the Palestinian diaspora

started after 1948, its history can be traced back to the history of the region

during and before British colonisation of the area. After the fall of the

Ottoman Empire in 1918, French and British colonialist powers with the

agreement of the Russians signed a secret agreement known as the Sykes-Picot

Agreement, to divide the Levant region, located in a large area of southwest

Asia, between them (see Map 1).

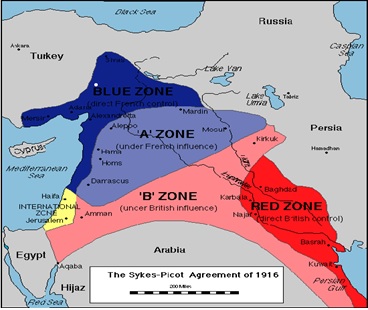

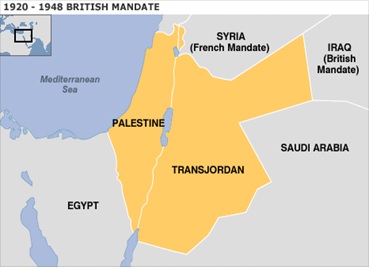

Britain was allocated Palestine, which nowadays constitutes the land occupied

by Israeli occupation forces, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, in addition to

Transjordan, which is now known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (see Map 2).

During this period, both Palestine

and Transjordan were under the British Mandate of Palestine. In 1917, the Balfour

Declaration was announced, which was in the form of a letter from the UK's

foreign secretary Arthur James Balfour to the Zionist federation. The letter

stated that Britain was in favour of giving a ‘home’ for the European and Arab

Jews in Palestine. Ever since this promise, Jewish refugees started migrating

to Palestine from around the world and began promoting the creation of the Zionist

state of ‘Israel’ on Palestinian land, under the British Mandate of Palestine.

This led to the General Assembly of the United Nations to adopt a resolution,

which recommended the termination of the British Mandate and the division of

the country into two states: one Arab and one Jewish. Therefore, on May 14,

1948, the Zionist entity announced its establishment, one day prior to the end

of the British Mandate.

Map 1 Sykes-Picot Agreement

Map 2 British Mandate of Palestine and

Transjordan

The issue of Palestinian refugees

emerged after the establishment of the Zionist state on Palestinian land in

1948, which resulted in the forced migration of 750,000 Palestinians. The

forced migration of Palestinians was called Al-Nakba, meaning ‘The Disaster’,

where individuals were forced to leave their houses, land and property and find

refuge in other countries, or in other areas in occupied Palestine (Abu Murad, 2004; Khalidi, 2005; UNHCR, 2000).

To respond to the Palestinian refugee issue, the United Nations Relief and

Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), was

established in 1949 by the UN General Assembly, to become the sole relief and

dedicated human development agency to provide Palestinian refugees with basic

necessities such as education, healthcare, social services and emergency aid in

the occupied Palestinian territories of the Gaza Strip, West Bank, and

neighbouring Arab countries including Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. The UNRWA’s

first response to Palestinian refugee flows was to provide them with temporary

tents, which due to their prolonged diaspora later had to be replaced with more

permanent shelters that eventually became permanent refugee camps. It is also worth

mentioning that there are Palestinian refugees in Iraq and Egypt, however, they

are not officially registered as refugees and thus are not eligible for

assistance from the UNRWA.

UNRWA’s remit is very limited to the

humanitarian aspects of refugees’ lives, in other words it explains that UNRWA

is only responsible for providing Palestinian refugees with basic needs and

relief assistance, and its work does not include helping Palestinians return to

their homelands and/or offering compensations for their loss. Ever since the

Israeli occupation of Palestine, Palestinian refugees and their descendants

have been struggling to attain their right to return, as political compromises

and Israel’s prevention of their return have so far prevented them from having

their demands realised, as Israel wants the Zionist state as an exclusively

Jewish state (Akram, 2002; UNHCR, 2000; Ehrlich, 2004).

Those 750,000 displaced individuals

have been hosted by neighbouring countries, such as Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and

Egypt, as well as neighbouring areas in Palestine itself, like the West Bank

and Gaza Strip (Khawaja, 2003).

However, the flow of Palestinian refugees did not stop in 1948. On the

contrary, more refugees subsequently fled to neighbouring countries; around

300,000 Palestinians were displaced in 1967 due to the Zionist occupation of

the whole Palestinian land resulting from the six-day war (Shiblak, 1996). Jordan has the majority of UNRWA registered

persons, and the number is estimated at 2,097,300, which leaves 1,258,600, 762,300,

480,000 and 450,000 people in the occupied Gaza, occupied West Bank, Syria and

Lebanon respectively. It is worth mentioning that most Palestinian refugees and

internally displaced persons live outside the camps (Badil, 2015). The total number of Palestinian refugees is estimated

at 7.25 million in total; 6.1 million became refugees after the first Zionist

occupation, which is known as Al-Nakba, and 1.113,200 million after the 1967 Zionist

occupation. 5.1 million Palestinian refugees are registered with the UNRWA, and

around 1.03 million are unregistered refugees (Badil, 2015).

There is a large amount of academic

and non-academic writings describing the bad situation of the Palestinian

refugees, which treats them as a homogenous community without shedding light on

gender, age, or class differences. For instance, El Abed (2006), Elsayed-Ali (2006), and Shiblak (2006) among many others have focused on

descriptively portraying the living conditions of the refugee population and

the discrimination they suffer, without taking differences into consideration.

The main difference that has been acknowledged in the secondary literature has

been the differences between host countries and their treatment of the refugee

population. For example, Palestinian refugees are allowed to seek employment in

Jordan, but are not allowed to do so in Lebanon. In Lebanon, the refugee

population is provided with a travel document to travel and they are not granted

Lebanese citizenship. They also face a big housing problem. There are also

official and unofficial camps and UNRWA is responsible for the maintenance of

official camps in Lebanon. However, since the 1990s the Lebanese government has

prevented any material entering the camps for maintenance purposes. On the

other hand, unofficial camp conditions are even worse, since most houses are

made of iron and do not offer adequate protection. In short, as El Sayed-Ali

states, the camps suffer ‘from serious problems—no proper infrastructure,

overcrowding, poverty and unemployment’ (Elsayed-Ali,

2006: 13).

In Jordan, on the other hand, many

Palestinian refugees who resided in Jordan after the 1948 Nakba were granted

Jordanian citizenship. Having Jordanian citizenship means that they and their

descendants have valid passports for five years, the right to vote and access

to governmental services. However, this does not mean that they are treated as

‘Jordanians’. As I mentioned earlier, Jordan has the largest number UNRWA registered

refugees. The situation of Palestinians in Jordan is therefore very precarious.

In theory they should be treated like ‘Transjordanians’[3].

However, in reality it is the opposite. Although Palestinians with Jordanian

citizenship are allowed to work in the public sector, they face widespread

discrimination and the majority therefore seek employment in the private

sector. There is also a huge gap between Palestinian refugees living in camps

and non-camp refugees, non-refugee Palestinians and Transjordanains.

The struggle of Palestinian refugees

has not only been relevant to their flight between 1948 and 1967, but is still

very much significant today, because their political status is not equal to

that of other refugees around the world. Their positions have not only been

influenced by Israel’s discriminatory policies, but also by their precarious

political, economic and social status in host countries. The issue of

Palestinian refugees has been thoroughly studied and analysed by many academics

who state that the influx of Palestinian refugees from 1948 ‘is not seen as the

outcome of random acts of violence against the Palestinian population, but is

depicted as the fruition of a long-standing colonial attitude by the Zionist

movement going back to the latter part of the nineteenth century and captured

by the slogan, “A land without a people for a people without a land”’ (Zureik, 2002: 2; Masalha, 1992; Khalidi,

1992). Yet, as previously mentioned, very little has been said about women

refugees and their unique experiences.

Palestinian Refugee Conditions

Before turning to the particular

experiences of Women Palestinian refugees, I want to begin by saying something

about the general conditions of the refugee camps, which I will later draw on

in teasing out the specific issues faced by women.

In Jordan, those who live in camps

are considered the poorest and least educated community; they are the most

marginalised and isolated. The camp conditions are poor in terms of

infrastructure. In addition to overcrowded conditions and very little

employment opportunities, Palestinian refugees who live in camps in Jordan are

unable to leave the camps because of high levels of poverty, and low levels of

education. In addition, they consider the camps as part of their Palestinian

identity, which they want to preserve. For example, during my visit to one

Jordanian camp, I learnt that many of these people have retained a very old

Palestinian accent, which was transmitted by their ancestors. Staying in the

camp also represents their own resistance and resilience and emphasising their

‘right of return’. They hope to return to their home country, which was taken

away from them in 1948 when the Zionist state was established.

In Lebanon, Palestinian refugees have

been considered the poorest group of people in the country and the poorest

amongst Palestinian refugees in other countries. Wadie Said criminalises the

Lebanese state for marginalising and refusing to accept Palestinian refugees as

citizens, especially since the prospect of their return is ‘as remote as ever’.

Palestinian refugees in Lebanon have not only had to tolerate the consequences

of war, but have also ‘remained confined in hideous quarantine for almost two

generations. They have no legal right to work in at least sixty occupations;

they are not adequately covered by medical insurance; they cannot travel and

return; they are the objects of suspicion and dislike’ (E. Said, 2001: 3).

In recent years, the situation in

Syria has affected the population of Palestinian refugees in both Syria and

Lebanon. As many Palestinians found themselves homeless in Syria, they sought

refuge in Lebanon, and the Lebanese government confined them to the Palestinian

refugee camps, causing even more overcrowding and poverty. Palestinian Syrian

refugees are treated differently from Syrian refugees. Syrian

refugees, for example, do not need tourist visas to enter Lebanon, whereas

Syrian-Palestinians do need ID documents, and in some cases entry permits. Additionally, the Lebanese

government has stopped renewing the residency of Syrian Palestinian refugees

and issued a decree to ban any Palestinian from entering the country.

As one interviewee stated: ‘we the

Palestinians have become homeless three times. My grandparents have fled the

Zionist occupation in 1948, then we had to leave Syria to Lebanon because of

the civil war, and in Lebanon we were imprisoned in camps and we were not

treated as human beings. So we fled to Turkey’ (Palestinian refugee interviewee in Turkey, 2013). Many of these Palestinians

who suffer from discrimination in Arab hosting countries had to leave for

Europe in boats through dangerous and life threatening routes, many have lost

their lives on the way.

Researching the ‘untouchables’: A Feminist Perspective.

Research carried out on Palestinian

refugees mainly focuses on describing their situation, such as, the refugee

camps and access to employment and education, in addition to their positioning

in the host countries (Abu Murad, 2004;

Khalidi, 2005; UNHCR, 2000). Other studies explore the experiences of Palestinian

women refugees in relation to their Palestinian national identity. For example,

a study, carried out by Hanafi (2011) in Palestinian refugee camps in

Lebanon and Syria, talks about women and their active resilient role in

transmitting their own narrative to their children about their homeland (Palestine).

He states that women ’enrich male-dominated history-telling with a female

tradition’ (Hanafi, 2011: 29). Those

studies reinforce women’s ascribed gender roles as ‘reproducers’ of the nation

and ‘bearers of the collective’, and in this case the narrative of the

Palestinian national identity is the main focus, rather than the experience

itself. In other words, using this narrative overlooks women’s experiences and

the discrimination they face because of their gender, and instead highlights

their position within the overall framework of national identity and struggle.

Thus women become part of the narration and an extension of the nation, rather

than independent entities, who might suffer from forms of oppression, in

addition to the occupation.

Moreover, based on research she

conducted in 1990 in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Abdo (1994) discusses

the concept of nationalism and feminism and how there is a huge difference

between state nationalism and the struggle for liberation nationalism. She

states that state nationalism is very much oppressive to women as it confines

women to the domestic sphere to just reproduce for the nation and create a

national identity through child bearing roles. She also states that this kind

of nationalism is not only sexist but also racist as it creates racial

discrimination (Abdo, 1994). For

example, the Zionist state encourages Jewish women to have children to increase

the number of Jewish people within its state boundaries. The Zionist state has

policies like ‘the fund for encouraging birth’, which gives housing loans to

families with more than three children. On the other hand, the Zionist state

has introduced policies, which target Arab women specifically. For example,

they have lowered the national insurance benefits for Arab Women and introduced

free contraception. She argues that the struggle for liberation nationalism can

be equally sexist for the use of certain narratives about women and men and

putting pressure on the role of women, however it is characterised by having

the ‘potential of being emancipatory and progressive’ (Abdo, 1994: 151).

I agree with Abdo’s argument

regarding gendered discrimination when it comes to national identity, either in

a state or a movement for the struggle for liberation. However, I disagree with

her on the point that the struggle for liberation can be more progressive and

emancipatory depending on women’s involvement to push their rights at the front.

Women’s rights are always pushed to the background because they are not seen a

‘priority’. Unfortunately, the struggle for liberation has become extremely

institutionalised and women’s rights have also been pushed away and been very

much boxed and framed to work within an agenda. Abdos’ article was written in

1990 when things were completely different and much more hopeful. Nowadays the

struggle for liberation is only one concern—refugees also have the struggle for

liberation from the Zionist occupation and also for liberation from the

Palestinian Authority, which is compromising more on the rights of the

Palestinians in general and the refugees in particular. This makes it even

harder for women to end patriarchal oppression.

Women’s roles are really important

when it comes to national movements. However, they are always seen as symbols

rather than active participants to end colonialism and oppression (Enloe, 1989). Women are used as symbols

not only against the coloniser but also in their own community. For example,

from one of my interviews, a Palestinian activist and feminist commented:

‘Palestinian women nowadays carry a huge burden, their role changes depending

on the political context and they become symbols. I know someone whose husband

was martyred, two months after their wedding.

She was forced by her family and her in-laws to wear a full burqa, if

she wanted to carry on with her education. Her status has changed, she has

become the wife of a martyr, and so she accepted to carry on with her education

and wear a full burqa’. The symbolic role that is given to Palestinian women is

applicable to all sections of the Palestinian community; it can be practised by

women from different classes and statuses, including refugee women living in

camps. Also, when women perform their ascribed symbolic gender roles, they are

always praised by men and their community for doing their job ‘properly’.

Enloe states that: ‘The more imminent

and coercive the threat posed by an outside power—a foreign force or the local

government’s police—the more successful men in the community are likely to be

in persuading women to keep quiet, to swallow their grievances and their

analyses. When a nationalist movement becomes militarised, either on its

leaders’ initiative or in reaction to external intimidation, male privilege in

the community usually becomes more entrenched’ (Enloe, 1989: 56). Based on my experience and conversations with

women activists, it has become apparent that targeting women’s ‘issues’ is not

considered necessary until the Palestinian people get their liberation. Therefore,

when women ask for gender equality, their request is crushed because women’s

‘issues’ are perceived as being ‘less’ important than ending occupation.

Nationalism and national movements

have certainly contributed towards women having spaces as national actors. However,

those national movements and nationalisms are very patriarchal and still place

women in inferior positions. Political oppressions and colonialism have indeed

contributed to hindering the development of different aspects of the lives of

the colonised and especially women. This is because nationalist narratives are

based on the premise that independence and liberation from colonisation is the

priority, and following that women’s liberation can be pursued.

A feminist approach to Palestinian

refugees does the opposite. By focusing on the experience of women from below

and through their eyes, I argue that there should be a shift when it comes to

talking about Palestinian refugees in Arab neighbouring countries. We should

adopt a feminist methodology to unpack the experiences of women refugees and

make their voices louder. I suggest that a feminist approach is the most

suitable, as it gives a complete picture of these female refugees’ experiences.

A feminist approach adds a more comprehensive analysis of the situation of refugees

to the literature, because it does not only look at their experiences from a

political perspective but also from a social and economic perspectives. Shalhoub-Kevorkian in her 2010 article ‘Palestinian

Women and the Politics of Invisibility: Towards a Feminist Methodology’ discusses the ‘Politics of

Invisibility’, in which she states that women’s voices and experiences are

often marginalised when there is war and conflict. She sheds light on the

importance of adopting a feminist methodology and involving women, especially

under such circumstances, in research, because their knowledge can ‘cast light

on the unprecedented levels of hegemonic military power that is used to-occupy

land, demolish homes, and wage unequal wars between civilians and the state- in

this case- the Israeli state’ (Shalhoub-Kevorkian,

2010: 1). The context of her study explores Palestinian women’s

experiences under Israeli colonialism and occupation. This article, by

contrast, particularly discusses the experiences of Palestinian refugees in

Arab neighbouring countries.

In order to fully understand

refugees’ situation, one therefore needs to take their experiences thoroughly

into account, because personal experiences have to great extent political

implications (Stanley and Wise, 1990;

Stanley and Wise, 1993; Klein, 1983). Additionally, a feminist

approach takes gender into consideration, through looking at how women’s

experiences are different from men’s. We can also see how gender can be used to

draw group boundaries within certain communities and, in the case the refugee

community, will enable a more complex picture of Palestinian Refugees to

emerge. Furthermore, I argue that refugee camp women suffer from more cultural

restrictions in comparison to other women because of the camp-specific

situation. Taking women’s experiences into consideration is not only important

because of cultural restrictions and patriarchy, but also important for

understanding the broader context in terms of displacement,

political violence, and economic exploitation and how that affects women

refugees differently.

Women in Refugee Camps

Whereas countries hosting Palestinian

refugees in the region are considered patriarchal, Palestinian refugee women

suffer from stricter patriarchal control in camps (El-Solh, 2003; Moghadam,

1993; Kandiyoti, 1988; Joseph, 1993; 1996). For example, Jordan is considered a patriarchal country

where it is expected that both men and women will adhere to specific gender

roles (Amawi, 2003). I observed

during my visits to the camps in the capital of Jordan that the areas are very

conservative, and the practise of patriarchy is clearly much more dominant than

in other parts of Amman. It has become apparent that people in Palestinian

refugee camps have maintained close personal bonds, which can be attributed to

the fact that this camp was established in the 1950s, just after the

establishment of the Zionist state on Palestinian lands. Due to the lack of

governmental support and protection, high poverty levels and isolation of the

camps from other parts of Jordan created subcultures within Palestinian camps.

In other words, there are economic, social and political differences between

people living within and outside the camps. This has created particular social

and cultural groupings, and in such circumstances gender can be one of the

markers for defining group borders. As Abu-Assab states: ‘Sexually, culturally,

and physically women are boundary markers for ethnic groups, and speaking of

gender relations in “other” ethnic groups or communities is frequently used as

a marker of difference. Gender relations often served to set group boundaries’

(Abu-Assab: 2012). However, in this

context I am not talking about ethnicity but rather about socioeconomic

differences between camp refugees and others. As a woman interviewee stated:

‘We have very different life-styles, very different. They have [a] very

different moral standing, we are more authentic in our lifestyles, women do not

dress modestly outside’ (Al-Wihdat

refugee camp, 2008).

The situation of refugee camps in

Jordan has a significant influence on women’s experiences. Such conditions make

the application of gender bias and patriarchy much more negative on women and

girls’ lives. Interestingly, place of residence influences women’s experiences,

as refugee camps are not considered ‘safe’ areas and consequently would

influence women’s mobility and freedom of movement. It has become apparent that

safety is very much linked to poverty in refugee camps. Female interviewees

mentioned that there are high crime levels because of poverty, which can lead

to women feeling ‘unsafe’ and can constitute a real physical danger. ‘Unsafe’

conditions in the camps can lead men to controlling women’s sexuality by

preventing them to move freely.

Distance from schools was a recurring

theme, which explained why some women had less access to education. Women from

refugee camps had to leave school at an early age because of the lack of

secondary schools in the area where they live. Distance from a school was an

issue that women’s families regarded as an issue of ‘safety’ and ‘protection’.

This shows that women’s access to education is limited by the social control exercised

by the male heads of household. Women explained how their families had in some

cases forced them into marriage and in other cases arranged for them to be married

because they could not afford to send them to distant schools. My research data

shows that poverty and camp situations reinforced patriarchal structures, as

women got married at early ages.

Enloe states that women always carry

the burden of the community instead of the men; men ascribe symbolic roles to

women, which can be manifested in different ways and affect women’s experiences

and lives. Women are seen as: “1) the community’s-or the nation’s most valuable

possession, 2) the principle vehicles for transmitting the whole nation’s

values from one generation to the next, 3) bearers of the community’s future

generations- crudely, nationalist wombs, 4) the members of the community most

vulnerable to defilement and exploitation by oppressive alien rulers, and 5)

most susceptible to assimilation and co-option by insidious outsiders”’ (Enloe, 1989: 54).

Conclusion

Sixty-seven years on, the Palestinian

refugee issue has not and should not be forgotten. Palestinians have been at

the crossroads, either in occupied Palestine and/or hosting countries.

Palestinian refugees and internally displaced Palestinians are always situated

at the intersection of any political, social and economic changes in the Arab

Middle East. For millions of Palestinian refugees, extreme poverty is only one

aspect of their struggle. Their precarious socio-political position contributes

to their feelings of instability and lack of political security in host

countries. Thus many still suffer the legacy of their dispossession: destitution,

impoverishment and insecurity. This article took a feminist approach to

understanding the experiences of women refugees; an approach that allows this marginalised

group of refugees a voice.

A feminist approach scrutinises the

position of women in nationalist movements and also refugee women, and

demonstrates that their experiences are different from their male counterparts.

I argue that women are assigned symbolic roles that are manifested in

materialistic ways. Those symbolic roles include women being the ‘bearers’ of

the nation and the reproducers. Those narratives undermine women’s experiences

as individuals and make them part of the collective, thus overlooking the

oppression they face because of their gender. It has become apparent that women

refugees in camps face different experiences in comparison to those of men, as

there are more restrictions on them and their mobility is controlled.

Recent events in the Arab World, such

as the situation in Syria, in addition to the discriminatory laws in Lebanon,

have lately disproportionately affected Palestinian refugees, as they never

enjoyed full citizenship in host countries. Most of the narrative surrounding

the experiences of refugees focuses heavily on nationalist sentiments, their ‘right

to return’, as well as their political, social and economic marginalisation. In

this article, I have demonstrated that the ‘issue’ of Palestinian refugees

should not be exclusive to men’s experiences, and it should include women. A

gendered examination should always be integrated into a study of refugee

experience to produce a more comprehensive analysis. I argue that the situation

of refugees is very much gendered as refugee women face different experiences

than those of men under those circumstances. On the basis of my discussion in

this article, it is clear that more research should be carried out to

critically assess and analyse the situation of refugees in general and women in

particular. It is also important to highlight that despite the fact that their

flight took place sixty-seven years ago, their situation remains very

different, depending on the political environment in which they settled and

remain at the mercy of their host countries. Policy makers must address the

needs of this vulnerable group, and bring more permanent and sustainable

solutions to their problems to the table.

References

Abdo, N. (1990),

‘Nationalism and Feminism: Palestinian Women and the Intifada’, in Moghadam, V.M.

(ed.) Gender and National Identity: Women and Politics in Muslim Societies, London: Zed Books, 148–170

Abu-Assab, N. (2012), ‘Narratives of Ethnicity and

Nationalism: A Case Study of Circassians in Jordan’, unpublished PhD thesis,

University of Warwick, UK

Akram, S. M. (2002), ‘Palestinian Refugees and Their Legal

Status: Rights, Politics, and Implications for a Just Solution’, Journal of Palestine Studies, 31, 36–51

Amawi, A. (2000), ‘Gender and Citizenship in Jordan’, in Joseph,

S. (ed.) Gender and Citizenship in the

Middle East, New York: Syracuse University Press

Abu Murad, T. A. (2004), ‘Palestinian Refugee Conditions

Associated with Intestinal Parasites and Diarrhoea: Nuseirat Refugee Camp as a

Case Study’, Public Health, 118, 131–42

Ehrlich, A. (2004), ‘On the Right of Return, Demography and

Ethnic-Cleansing in the Present Phase of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’, Orient - Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Politik

und Wirtschaft des Orients, 45, 549–563

El Abed, O. (2009), Unprotected:

Palestinians in Egypt since 1948, Canada: IDRC

El Abed, O. (2006), ‘Immobile Palestinians: ongoing plight of

Gazans in Jordan’, Forced Migration

Review 26, 17–18

El Abed, O. (2004), ‘The forgotten Palestinians: how Palestinian

refugees survive in Egypt’, Forced

migration review, 20, 29–31

El Sayed- Ali, S. (2006), ‘Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon’, Forced Migration Review, 26, 13–14

El-Solh, C. F. (2003), ‘Gender, Poverty and Employment in the

Arab Region’, Geneva, Capacity-Building

Program on Gender Poverty and Employment & National Policy Group

Enloe, C. (1989), Bananas,

Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics, London:

Pandora Press

Joseph, S. (1993), ‘Gender and Relationality Among Arab

Families in Lebanon’, Feminist Studies,

19, 465–86

Joseph, S. (1996), ‘Patriarchy and Development in the Arab World’,

Gender and Development, 4, 14–19

Hanafi, S. (2011)

‘Governing the Palestinian Refugee Camps in Lebanon and Syria: The Case of Nahr

el-Bared and Yarmuk Camps’, in Knudsen, A. & Hanafi, S. (eds) Palestinian

Refugees: Identity, Space and Place in the Levant, USA: Routledge, 14–29

Kandiyoti, D. (1988), ‘Bargaining with Patriarchy’, Gender and Society, 2, 274–90

Khalidi, W. ed. (1992), All

That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in

1948, Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies

Khalidi, W. (2005) ‘Why Did the Palestinians Leave, Revisited’,

Journal of Palestine Studies, 34, 42–54

Khawaja, M. (2003), ‘Migration and the Reproduction of

Poverty: The Refugee Camps in Jordan’, International

Migration, 41, 27–57

Klein, R. D. (1983), ‘How to do what we want to do: Thoughts

about feminist methodology’, in Bowles, G. & Klein, R. D. (eds.) Theories of Women's Studies, London:

Routledge and Kegan Paul

Masalha, N. (1992), Expulsion

of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought,

1882–1948, Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies

Massad, J. A. (2001), Colonial

Effects: The Making of National Identity in Jordan, New York: Columbia

University Press

Moghadam, V. M. (1993), Modernising

Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East, Colorado: Lynne Rienner

Reinharz, S. (1992), Feminist

Methods in Social Research, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Reinharz, S. (1997), ‘Who Am I? The Need for a Variety of

Selves in the Field’, in Hertz, R. (ed.) Reflexivity

and Voice, London: Sage Publications

Roseneil, S. (1993) ‘Greenham Revisited: Researching Myself

and my Sisters’, in Hobbs, D. & May, T. (eds.) Interpreting the Field: Accounts of Ethnography, Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Q & A: ‘What you need to know about Palestinian Refugees

and Internally Displaced Persons, 2015’. Badil: Resource Centre for Palestinian

Residency and Refugee Rights: http://www.badil.org/en/press-releases/149-2015/4451-pren19051515 [accessed 16/06/2015]

Said, E. (2001), ‘Introduction: The Right of Return at Last’,

in N. Aruri (ed.), Palestinian Refugees: The Right of Return, Pluto

Press, London, 1–35

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. (2010), ‘Palestinian Women and the

Politics of Invisibility: Towards a Feminist Methodology’, Peace Prints: South Asian Journal of Peace building, 3(1): http://mada-research.org/en/2013/07/28/palestinian-women-and-the-politics-of-invisibility-towards-a-feminist-methodology-nadera-shalhoub-kevorkian-2/ [accessed 30/10/2015]

Shiblak, A. (1996), ‘Residency status and civil rights of

Palestinian refugees in Arab countries’, Journal

of Palestine Studies, 25(3), 36–45

Shiblak, A. (2006), ‘Stateless Palestinians’, Forced Migration Review, 26, 8–9: http://www.fmreview.org/FMRpdfs/FMR26/FMR2603.pdf [accessed 30/10/2015]

Stanley, L. & Wise, S. (1990), ‘Method, Methodology and

Epistemology in Feminist Research Processes’, in Stanley, L. (ed.) Feminist Praxis: Research, Theory and

Epistemology in Feminist Sociology, London: Routledge

Stanley, L. & Wise, S. (1993) Breaking Out Again: Feminist Ontology and Epistemology London, London:

Routledge

Zureik, E. (2002), ‘The Palestinian Refugee Problem:

Conflicting Interpretations’, Global

Dialogue, 4(3): http://www.worlddialogue.org/content.php?id=237 [accessed 30/10/2015]

To cite this

article:

[1]

Undertaken at the University of Warwick between 2007 and 2008, partly funded by

Birzeit University and Gender Economic Research and Policy Analysis (GERPA).

Research participants were chosen using a snowballing technique so sampling was

opportunistic and were asked the same interview questions. For this research, I

obtained ethical approval from the University of Warwick to carry out my

research.

[2]

The Centre for Transnational Development and

Collaboration carries out research on vulnerable groups across the world. Part

of its work has been undertaken among displaced Syrians and Palestinians. The

Centre has permitted the use of this data for this publication: www.ctdc.org

[3]

Transjordanians is a term

adapted during the British Mandate of Palestine and Transjordan to describe the

native inhabitants of what is now known as Jordan.