|

|

|

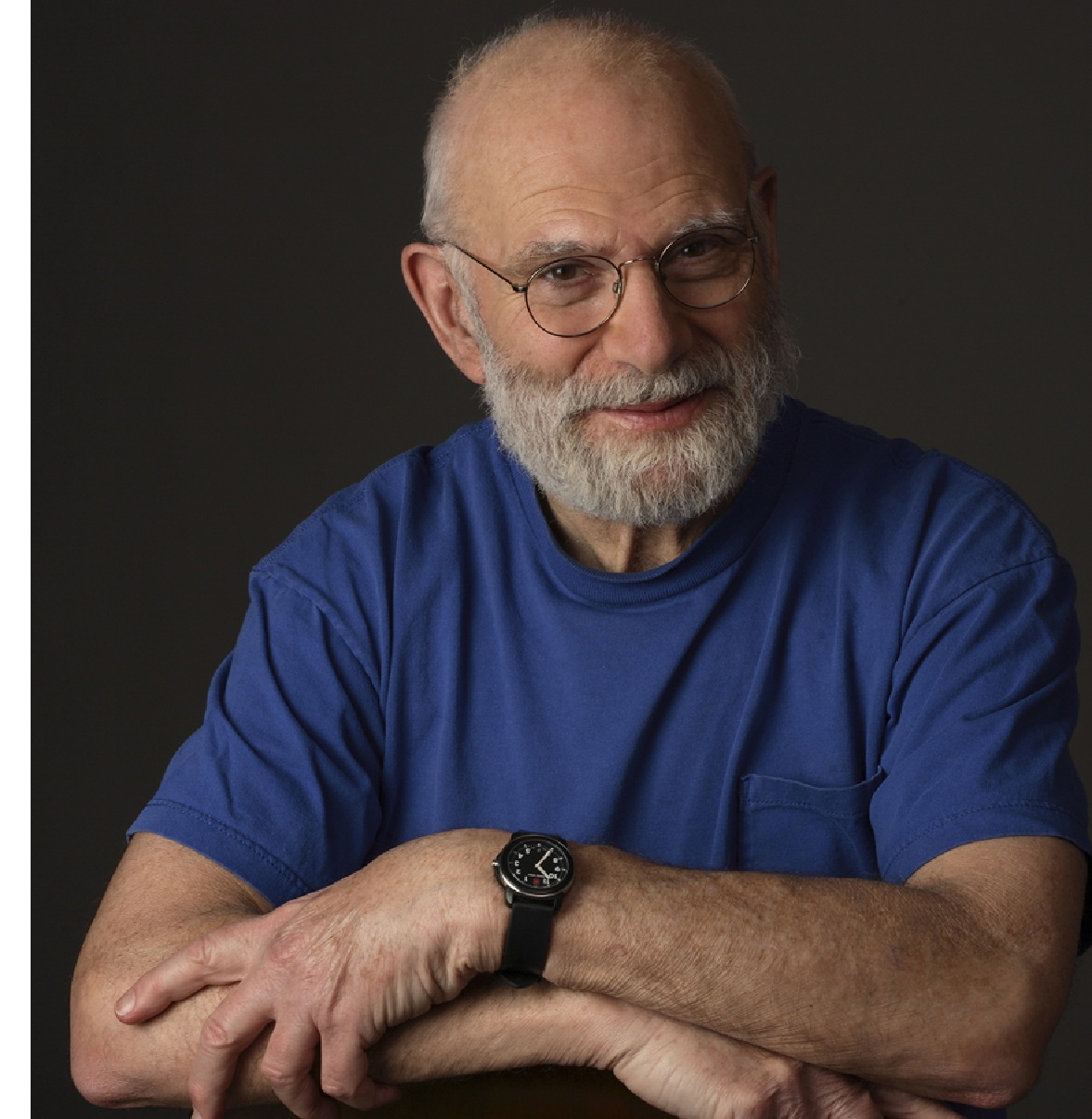

‘Exchanges’ – Conversations with… Oliver Sacks

Julie Walsh, University

of Warwick

Renowned neurologist and

author Dr Oliver Sacks is a visiting professor at the

University of Warwick as part of the Institute of Advanced

Study. Dr Sacks was born in London. He earned his medical

degree at the University of Oxford (Queen’s College) and the

Middlesex Hospital (now UCL), followed by residencies and

fellowships at Mt. Zion Hospital in San Francisco and at

University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). As well as

authoring best-selling books such as Awakenings

and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, he is

professor of neurology at NYU School of Medicine in New

York. Warwick is part of a consortium led by New York

University which is building an applied science research

institute, the Center for Urban Science and Progress (CUSP)![]() . Dr Sacks recently completed

a five-year residency at Columbia University in New York,

where he was professor of neurology and psychiatry. He also

held the title of Columbia University Artist, in recognition

of his contributions to the arts as well as to medicine. He

is a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and the

Association of British Neurologists, the American Academy of

Arts and Sciences, and the American Academy of Arts and

Letters, and has been a fellow of the New York Institute for

the Humanities at NYU for more than 25 years. In 2008, he

was appointed CBE. (University of Warwick, 2012)

. Dr Sacks recently completed

a five-year residency at Columbia University in New York,

where he was professor of neurology and psychiatry. He also

held the title of Columbia University Artist, in recognition

of his contributions to the arts as well as to medicine. He

is a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and the

Association of British Neurologists, the American Academy of

Arts and Sciences, and the American Academy of Arts and

Letters, and has been a fellow of the New York Institute for

the Humanities at NYU for more than 25 years. In 2008, he

was appointed CBE. (University of Warwick, 2012)

...it still

strikes me myself as strange that the case histories I write

should read like short stories

and that, as one might say, they lack the serious stamp of

science. I must console myself with the reflection that the

nature of the subject is evidently responsible for this,

rather than any preference of my own. (Sigmund Freud, 1895)

I have no “literary” aspirations whatever,

and if I write “Clinical Tales” it is because I am forced to; because

they do not seem to me a gratuitous or arbitrary compound of

two forms, but an elemental form which is indispensable for

medical understanding, practice, and communication. (Oliver

Sacks, 1986)

I have always been

intrigued by the logic of writing down notes (clinical

or otherwise) in order then to write them up. What is it

exactly that happens between these stages of writing? Can we

really say that the first is a simple act of recording or

documenting, while the second is a more elaborate process of

reconstruction? The

‘write up’ perhaps brings to mind the more ambiguous notion of

the ‘stitch up’ with its connotations of fabrication and

wilful misrepresentation. Similarly, the figurative use of the

verb ‘to doctor’ – as in to doctor the evidence – might remind us of the

multiple powers that reside in the personage of the physician

who may be writing up and/or stitching up your case. It would

seem that the capacity to disguise or dissemble is somehow

integral to the project of clinical writing. But so too must

the idea of the ‘stitch up’ imply the physician’s care, his

work of suturing a wound, or attending to the frayed nerves of

a patient. Finding its highpoint in the clinical narrative or

case-history, the ameliorative power of storytelling can also

be read as a desire to assuage the patient’s suffering; to

give form to the fractured or dislocated elements of

experience. And what of the pleasures of spinning a yarn?

From his first book, Migraine (1970), to

his most recent, Hallucinations

(2012), Oliver Sacks has finessed the art of the ‘clinical

tale’. With it he has conveyed the many ways in which the

fabric of one’s personal identity can become unstitched by a

range of neuropathological phenomena. As a medical

practitioner and a writer, Sacks holds that the greater

endeavour of medicine is to help an individual construct a

life; this means that medicine’s modes of communication need

to be equal to the task.

For Sacks, to rehabilitate the case history as a form

of writing inevitably means that the patient’s story becomes

the tale of an embattled protagonist striving to preserve a

coherent identity in adverse circumstances.[1]

|

|

In his recent lecture here

at Warwick (available on video via

the University website), Sacks reminded his audience

of the historical drift since the nineteenth century that has

occurred in science writing – and in medicine in particular –

towards greater classification at the expense of detailed

descriptions of the patient’s idiosyncratic experience. Sacks’ attention to

the idiosyncratic details, and the care he takes in presenting

them, doubtless accounts for his appeal as a writer and his

success as a physician. But

are there any tensions between the dramatic impulse of the

case history, thus conceived, and the physician’s fidelity to

the facticity of the case?

If the case history is to become germane to medical

methodology once more, how are we to think about its

production of ‘truth’ (whether for the patient, the doctor

and/or the reader)? And

most curiously, for me at least, in what ways does the

storyteller reveal himself

in the act of telling another’s

story?

I first engaged with Sacks’

work on my undergraduate Sociology degree here at Warwick. We were learning to

think about the relation between identity, memory and trauma,

both from the personal or autobiographical perspective, and in

relation to questions of collective identity in the context of

twentieth-century cultural history. In The Man Who Mistook His

Wife for a Hat (or his Hat book, as Sacks calls it) we found stories

to demonstrate the precariousness of personal identity.

Critically, for the student of sociology, Sacks’ work offered

an unusual lens – what we might call the lens of ‘neurological

self-hood’ – for viewing how one’s capacity to sustain a

stable sense of self can be disrupted. More recently I’ve

returned to Sacks’ work with a view to thinking about the

affinities between his research questions and those of

psychoanalysis. When I asked Dr Sacks to reflect on the place

of psychoanalysis, and of Sigmund Freud, in his life and work

it was clear that there were several lines of thought to

pursue. Freud the writer of case histories provides a clear

precedent for Sacks. Then there is the therapeutic

experience of psychoanalysis to consider, especially its

clinical practice of reading the self beyond its most obvious

presentations. Indeed,

Sacks discussed with me how his long standing personal

analysis may have strengthened his habit and skill as a

listener. But

perhaps it is the early Freud – the neurologist in gradual

pursuit of a scientific psychology – that Sacks is most able

to admire.[2]

In the course of our interview Sacks told me about his great

love for marine biology, and how at one point in his career –

‘between the chemical days and the medical days’ – he had

wanted to spend his life’s work on the nervous systems and

behaviours of invertebrates. If it is difficult to reconcile

such a wish with the deeply human commitment to

medicine and science for which Sacks is now renowned, we

should remember that the impulse to keep these dimensions

distinct – to carve up the world according to different kinds in order to

limit one’s engagement with it – runs counter to Sacks’

general approach. Sacks told me that one of the things Freud

had a very clear feeling about was the importance of continuity between

all life forms: ‘in

his paper on crayfish ganglia [Freud] brings out that the

nerve cells are essentially similar to the nerve cells of

mammals or human beings; it’s not the nerve cells […] which

are different, but their number and organisation’. The

provocative question that Sacks raises from Freud’s commitment

to continuity concerns the boundaries of mental life: where

does mental life begin and end? For Sacks’ Freud, the mental

is not confined to human beings.

When I met with Dr Sacks

earlier this month he warned me that he had a tendency to

‘gabble’ and that my questions were ‘liable to release ten

minutes of nonsense’ from him.

Nothing could have been further from the truth, but we

did hit upon a felicitous affinity between his areas of

research expertise and the particular mode of attention that

allows for productive meanderings off topic (or seemingly off topic). I had asked about

the rituals that attach themselves to his writing habit.

Sacks, by and large, has always been a hand writer. His desk

was sectioned with different papers, pads, and numerous pens

ordered for various purposes, and his shelves were stacked

with journals and notebooks going back years; there were three

journals (A5 hardback notebooks) that contained notes from a

single month in 1987. He

mentioned his preference for a particular thick-paged notebook

in which one can write on both sides and, critically, that has

no lines. ‘Do you know what delirium means, literally?’, asked

Sacks ‘it means not staying between the lines’. A quick

consultation with the nearby dictionary confirmed it: delirium

from dēlīrāre:

prefix de as in

from, and lira as in furrow; ‘so

it’s to turn, to turn away from the furrow’. Likewise, he told

me, Hallucinations

– the title of his most recent book – connotes a wandering in

mind, or a not sticking to the point.

Many of the wanderings our

conversation took have not been captured in the extract below:

for example, the importance of recognising the existence of

mental life in non-human species; the distinction between

‘mind’ and ‘brain’; the possibility of a basic incompatibility

between ‘organic’ aetiologies and what we might call

‘psychosocial’ ones. Such are the omissions of this particular

write up. What follows focusses on the line of discussion to

which we kept returning: namely, what it means to write a case

history. By the end of our time together Sacks had impressed

on me the challenge of being ‘essentially faithful’ to the

clinical material in question whilst not disavowing the

inevitable ‘gap between experience and art’.

***

OS: I’m in a writing spell now,

but I wasn’t a month ago and I had an arid time in the summer.

JW: Can you sit quite

comfortably with that?

OS: No! I’m a miserable person

then, and I make other people miserable.

JW: Unless you’re writing?

OS: When I’m writing I become

much happier, the neuroses fall away, I don’t bother people, I

see the best of people, I elicit the best of people. And, in

this way, writing is absolutely essential for my health and

wellbeing.

JW: One of the questions you

ask in your work, and it’s a problem I’m also very taken by,

is the question of what constitutes a tenable life. I noticed in The New York Times recently

[The Joy of Old Age],

you evoked the Freudian wisdom whereby what makes a life

tenable is the capacity to love and work.[3] It’s interesting to

hear you reflect on the fact that writing, for you, makes your

life tenable, so to speak. I think this really does key into

your emphasis on the value of narrative, doesn’t it?

OS: On the value of work.

JW: Yes, and work.

OS: Yes, in particular your work; one’s work, which is

also one’s identity, or part of one’s identity. Although I don’t

know that I’ve ever quite identified myself as a writer. I was asked in an

interview some years ago, what are you first, a physician or a

writer? I said a

physician but they inverted the order and said a writer, which

sort of annoyed me. Though I think the real answer is that

they tend to go together and perhaps (as if I were a novelist)

people around me – my friends as well as my patients – are in

danger, so to speak, because they may be turned into material!

Although with my patients

I’m slow to write about them, I feel I have to know them

fairly well, and then I will discuss the matter with them and

see how they feel. I’m

not satisfied with a formal consent, I have to feel they would

be comfortable and I will usually send them what I write and

ask them to correct or comment. By that time they may say,

I’ve changed my mind; leave me out.

JW: Ah, okay, and will you do

that, if they have changed their mind?

OS: If it’s a radical change

of mind I might. Or

there may be minor changes. This was the case with one

relatively early piece of mine on a man with Tourette’s called

Witty Ticcy Ray

which was later collected in the Hat book.[4] [When I wrote the

piece] I’d been seeing him at that point for ten years, since

‘71. And I asked

Ray (this was not his real name) if he’d care to read it and

he said no, that’s okay, I trust you. And I said, well I think

you should read it, and he said, well, okay, why don’t you

come to dinner on Friday.

As he was reading it, I noticed various tics and I was

getting nervous and he said rather explosively, you take some liberties! I pulled out my red

pen and said, what should I erase, what should I change? In

the end he shook his head and said, leave it, it’s essentially true, he

said, but don’t publish here in New York – why don’t you

publish it in England. So it was published in The London Review of

Books. At

that point I thought that if I published in London it would,

to some extent, protect my patients in New York – although I’d

learned with Awakenings

that this was not always the case. One of my Awakenings patients,

a very bright woman, who got wind of the fact that the book

had been published in England, somehow got a copy. And now, if I write

a piece, it’s ‘out there’.

Which reminds me, I’m

bewildered and often horrified about the nature of blogs,

which seem to erase some of the distinction between private

and public, and I think they’re rather dangerous.

JW: But isn’t that also a

danger that your work inevitably encounters?

OS: Yes.

JW: So, Ray’s response, ‘you

take some liberties’ is relevant here. First of all there’s

the very simple truth that we can never know whether the

patient is going to be able to say, ‘yes, that does me

justice’ or ‘yes, that accords with my own understanding of

the situation’ or ‘that is essentially true’. And this is

precisely one of the dangers of clinical writing; the

inevitable misrepresentations and moments that expose a

disconnect between two different accounts of an experience. It

can be quite anxiety inducing!

But then again, and I think your work demonstrates this

so well, clinical writing is also enjoyable. In my own work, I

worry about that enjoyment. Because, well, it’s a difficult

type of enjoyment – or pleasure – to take, isn’t it?

OS: It is. And it’s a very

central thing for me. My

Migraine book has

only little vignettes and there are really no recognisable

characters. But then in 1970 I submitted some letters, medical

letters, to the Lancet

about some of my patients on L-dopa. A few weeks later the

sister of one of my patients came up to me holding the New York Daily News in

her hand and she said, is this your medical discretion? Unknown to me, the Lancet had released

the letter to a wire service, and it had been picked up by a

newspaper here. She

wasn’t upset or offended, she said probably no-one but

immediate family would have recognised her sister. But this

worried me somewhat. I

usually make some disguise, alter identifying details, but

obviously in that letter I had not disguised enough.

JW: And perhaps even the

notion of ‘disguise’ is problematic?

OS: Yes.

JW: Because that’s actually

about literary creation, isn’t it? So, in ethically

disguising the identity of the patient one is also creatively

dissembling.

OS: Yes.

JW: And fictionalising!

OS: Right. Yes, well with Ray

it was fairly light: I changed his name and I changed where he

lived. But to

what extent is dissembling, as you put it, compatible with

truth? Big

question!

JW: It is the big question!

OS: Something drifted in and

out of my mind. I want to say this: It has been brought up in

various forms, sometimes rather traumatic forms; a critic

called Tom Shakespeare once called me “the man who mistakes

his patients for a literary career,” which hurt, and which

stays in my mind even thirty years later. I feel that first as

a physician I have to respect the patient, and to be tactful

and delicate. There are some things where curiosity would make

me want to push further and I have to say, no, at least not

now. I hope my writings, such as they are, are in the mode of

delicacy and respect.

I was very pleased when Mrs

P, the woman mistaken for a hat, after her husband’s death,

went to see the opera by Michael Nyman.[5]

I watched her closely at the performance, wondering what

[she’d make of the piece], but she came up to us, the script

writer and the musician and myself, and she said, you have

done honour to my husband. And that was very nice; we all gave

a big gasp of relief.

JW: Yes! So I wonder if your

solemn feeling of responsibility impacts on whether or not you

wish to collaborate with others in your writing? I mean I‘ve

noticed that you include your readers and the correspondence

you get with your readers as part of your practice.

OS: I do now.

JW: So in a way I suppose we

can think of your use of letters as a collaborative writing

practice. But, exempting the artworks, have you ever wanted to

actually sit down and write collaboratively with another?

OS: I think the simple answer

is no. Peter

Brook phoned me some years ago and said he wanted to do a

theatre evening called ‘The Man Who…’ drawing on many things. I introduced him to

one or two patients, and I then basically said, it’s up to

you. And I felt

the same with Pinter when he wrote A Kind of Alaska.[6]

In the movie of Awakenings,

I was there only as a sort of technical advisor, for medical

details.[7] I disliked one scene

in the movie when there’s a sort of fight in the lobby of the

hospital and I walked off the set angrily. When I saw it made

no difference, I came back to the set quietly and kept my

mouth shut and thought, it’s theirs, not mine.

JW: I’m really curious to

hear how you understand the relationship between your clinical

writing and the writing of your own memoir; your own case

history. These two modes of writing have to be in dialogue

somehow. And I think my feeling is that all writing is

autobiographical.

OS: Yes, Tolstoy said that

everything he wrote was part of one giant confession. And then of course

Joyce talks about the artist being ubiquitous but invisible. I fear I’ve let

myself become more and more visible!

JW: And why would that be a

fear?

OS: Well, in Awakenings more than

Migraine I had

become a figure in patients’ lives. I got the drug, I watched

them, I felt guilty and appalled when they started to get bad

effects of one sort or another, and when one of my patients

then called L-dopa ‘Hell-dopa’. I lived through the whole

experience with them. But in a way my Leg book [A Leg to Stand On]

became a sort of case history of myself, and in The Mind’s Eye I’ve

given an explicit account of being a patient. But also I think in

other books I’ve sort of thrown myself in, as I would throw

anyone in, because of a particular phenomenon or symptom. So

say in my chapter on amusia,

in Musicophilia, I

mention a couple of times when I had amusia with a

migraine, as part of a migraine aura. And in The Mind’s Eye, when

I’m writing about alexia,

I again mention a personal example.

JW: So, you become a character

in the lives of your patients, and you can also use yourself

as a resource when you’ve been a patient in a particular

medical context. But

there’s another context in which your patient-hood is at

stake, and you allow us just a slight glimpse of this in your

Hallucinations book.

OS: Oh yes, my Chapter Six.

JW: Yes, your chapter on

‘Altered States’. So, you tell us that in the mid-sixties you

entered an analysis following your friend’s astute observation

that your experimentation with mind-altering drugs may in fact

be masking some inner conflicts. I’d be very interested to

hear about what it was like to be that type of patient, and

also to think with you about how the experience of analysis

may have mapped on to the development of your ethos and your

style as a writer.

OS: Well, in December, New

Year’s Eve of ‘65, when I was fizzing and sort of manic with

amphetamine, and had lost a great deal of weight, I had a sort

of lucid moment when I saw my gaunt – my then gaunt – face in

the mirror and I said to myself, you will not see another New

Year’s Day unless there’s intervention. I had been seeing an

analyst a little bit in Los Angeles, it didn’t seem to get

anywhere, partly I think because I was always stoned when I

saw him, or often stoned. This allowed me to produce some

associations with vertiginous rapidity but they were somehow,

you know, all on the surface of my mind; nothing really got

in, or went deep. In Los Angeles when Doctor Bird said to me,

why are you here? I said, ask Doctor Bonnard, she referred me!

So, you know, my heart wasn’t in it. Whereas in ‘66, I

sought help for myself, knowing I was in danger. The analyst I

saw then is still my analyst; I saw him yesterday and we are

now in our forty-seventh, forty-eighth year.

JW: My goodness me!

OS: I see him twice

a week and if I’m away somewhere I will phone if I can. I’ve

even phoned from a cell phone from the middle of a desert, or

something like that. And

I dedicated my Hat

book to him.

I think that the habit and

skill of listening carefully, not interrupting too much, and

trying to divine what may be going on behind the words is a

sort of – I think this has to be the case with all doctors and

maybe with all people – has been strengthened by seeing him.

I think one no longer

speaks of analysts as ‘Freudian’ or whatever, but although my

own analyst has the Collected

Works [of Freud], doubtless, he is very sensitive to

biological factors as well. I think I mentioned this actually

in Hallucinations

in the chapter on delirium: I’d started having some very

peculiar dreams when I was in Brazil, but I’d had diarrhoea

and a fever and this and that, and I thought they would settle

down but they didn’t. I

had these extraordinary Jane Austen-like dreams which were

very atypical and I would wake and have a cup of tea and go

back and I would be in the same dream except it would have

moved on a chapter, or two months later. I had the feeling it

was a narrative saying itself, whether I was awake or asleep.

After about a couple of weeks my analyst said, you’ve produced

more dreams in the last two weeks than in the previous twenty

years, are you on something?

And I said no, and then I said well, actually I am, I

was started on Lariam to prevent malaria. Lariam used to be

given to all the armed forces here, and may have played a part

in their breakdowns and violence when some of them came back. But it is now a drug

handled very carefully and it really shouldn’t have been given

to me, it’s only of use for the sort of malaria one has in

South East Asia. But

Lariam is now well known for producing bizarre dreams,

hallucinations, and psychoses.

Anyhow this was an example of [my analyst] saying,

something else may be going on here.

I should say that he

himself [has] written several books and he displays far more

reserve and reticence than I do when he talks of his patients. With some difficulty

I detected a possible reference to myself, maybe conflated

with others, in one of his books. I was actually

rather sorry it wasn’t more of a reference.

***

References

Breuer, J and Freud, S. (1955 [1895]), Studies on Hysteria

in The Standard Edition

of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud,

Volume II (1893-1895). (Trans. & ed.) James Strachey.

London: the Hogarth Press.

Sacks, O. (1970), Migraine. London:

Faber and Faber Limited.

--- (1973), Awakenings. London:

Duckworth.

--- (1984), A Leg to Stand On.

New York: Touchstone Books.

--- (1985), The Man Who Mistook his

Wife for a Hat. London: Picador.

--- (1986), ‘Clinical Tales’ in

Literature and Medicine

5: 16-23.

--- (2000 [1998]), ‘The

Other Road: Freud the Neurologist’ in Freud Conflict and

Culture: Essays on His Life, Work, and Legacy. (ed.)

Michael Roth. New York: Vintage Books: 221-234.

--- (2007), Musicophilia. London:

Picador.

--- (2010), The Mind’s Eye. New York: Alfred A.

Knopf

--- (2012), Hallucinations. London:

Picador.

--- (2013), ‘The Joy of Old

Age. (No Kidding.)’ in The

New York Times (July 6), Accessed online 10/7/13, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/07/opinion/sunday/the-joy-of-old-age-no-kidding.html?_r=0

University of Warwick (2012),

Press Release 173, 10th October 2012, Accessed

online 30/9/13 http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases/dr_oliver_sacks/

[1]

The phrase ‘striving to preserve its identity in adverse

circumstances’ is one that Sacks borrows from Ivy McKenzie

whose work on Encephalitis he greatly admires (see for

example Sacks 1986, or his Warwick DLS lecture)

[2]

See

Sacks’ ‘The Other Road: Freud the Neurologist’ (1986)

[3]

Whilst arguably in keeping with the Freudian Weltanschauung (or

worldview), this phrase -the capacity to love

and work- is

not in fact found in Freud’s writing (see

http://www.freud.org.uk/about/faq/).

[4]

‘Witty Ticcy Ray’ was first published in the London Review of Books

(1981) and then collected in The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat (1985).

[5]

The Man Who Mistook

His Wife for a Hat inspired a Michael Nyman opera in

1986.

[6]

Harold Pinter acknowledged the influence of Awakenings on his

1982 play A Kind of

Alaska.

[7]

In 1990 Penny Marshall directed a film adaptation of Awakenings.