Modelling

social mobilisation – an interdisciplinary exploration

of twitter as a mediating tool for social acts and information networks

Dr

J.D.

Amor, Dr J. Foss, Dr G. Gkotsis, Dr H. Grainger-Clemson, E. Marchis, F.

Azhar

Abstract

In

recent years,

researchers, social commentators and the mass media have turned their

attention

to shifts in the use of social media for political and social action.

This

article provides an overview of the recent discussions focusing on how

Twitter

specifically functions as a mediating tool for social acts. We present

findings

from a recent pilot project exploring the mechanics of disseminating

information via Twitter across a dynamic human network in order to

contribute

to an understanding of how people use social media to share information

and

prompt others into action, and outline some approaches for performing

this

analysis. Taking the perspective of communities of users operating in

hybrid

spaces, we make recommendations for further research in this field.

Keywords

Twitter,

hybrid spaces, social networks, social acts, information flow

Introduction

We

are witnessing a paradigm change in collective

mobilisation ... from solidarity to fluidarity

...from collective mobilisation to the mobilisation of

a collective of

people and technologies ... a hybrid crowd. (Lasen & Martinez de

Albeniz,

2011:155)

In

recent years, researchers,

social commentators and the mass media have turned their attention to

shifts in

the use of social media for political and social action. Since its

launch in

2006, the microblogging platform ‘Twitter’ has become

increasingly popular and

powerful in assisting the ordinary person make public

‘acts’ of information

sharing and social commentary. Gillan and Merchant (2013) argue that it

has

achieved “a

new level of institutionalisation as it features in legal

cases, debates about privacy, and political intrigue” (2013:47).

In

its broadest sense, we conceptualise these social acts,

along with phenomena supported by social media such as flash mobs and

even more

violent happenings such as riots, as a form of desired social

‘mobilisation’.

The concepts of ‘hybrid spaces’ –

merging people, technologies, and online spaces - and

‘homophilly’ - the principle that we tend

to be similar to our friends - can offer a useful lens through which to

understand how people are persuaded to come together virtually and

physically.

In

this article, we discuss recent

literature that reveals recent perspectives on the role of social media

in

social networks and movements.Building on this, we discuss the

functions of

Twitter and the potential role it can play in mediating social acts and

find

that closer studies of the ‘Individual User – Tool

(Twitter) – Other User’

interface may contribute greatly to our understanding of the

possibilities for

this tool in social network formation and how individuals and

communities

collectively create meaning and make sense of the world around them. In

order

to provide a ‘real world’ example we present the

methodology and findings of a

recent empirical pilot study that created an open interactive Twitter

event on

a University campus giant video screen in order to investigate how

Twitter

functions as a mediating tool between direct human engagement and that

individual working within a group or ‘network’. We

intentionally created a

cross-discipline research team to bring a range of expertise and to

explore the

possibilities for a mixed methods approach, and we reflect this in the

format

of the article, through the collaborative authorship and through the

findings

that are based on qualitative data and computational modelling. We

conclude that effective ways of mapping a

social network can reveal its information flow, connectedness, and

communities,

as well as give a sense of more complex triangular relationships and

homophily By

combining a data-driven, network analysis approach with a

sociologically driven

qualitative analysis it is possible to derive a deeper insight into the

operation of a hybrid network than is possible through using one

approach in

isolation.

Recent

perspectives on the role of

social media in social networks and movements

The

forming of social networks

Social

networks can be defined as

“social structures that can be represented as...sets

of nodes (for

social system members) and sets of ties

depicting their interconnections” (Wellman and Berkowitz 1988,

cited in Zhao et

al 2011:5). Actors in a network can be individuals, groups or

organisations

that are connected in some way via certain relationships. However,

these

relationships do not exist in vacuum as we are located in different

places from

and to which we share information. This is what forms our

‘network society’

(Castells 2000). Our interaction with the external physical world is in

part

mediated by the technological tools we are both presented with and

choose to

carry about our person. Through our phones, tablets, and even simple

cameras

and music devices, we are able to reflect upon, capture, and connect

with a

place in a moment in time. Alternatively humans can make connections to

other

networks and be transported elsewhere or bring that other to where we

are (de

Souza e Silva & Delacruz 2006).

Social

media plays a dual role in

acts for social change: communication across the network of

participating

actors, but also sharing commentary across a wider network of

onlookers. It

comprises content, user communities and Web technologies, and networks,

which

mean that new ideas spread very quickly (Ahlqvist et. al. 2008). The

principle

that we tend to be similar to our friends

–‘homophily’ – is important in

determining the information that we are exposed to and share within

these

particular relationships; including as

friends on Facebook or followers on Twitter. Social selection –

the

circumstances that determine the people we are friends with - and

social

influence - the way we ‘fit in’ with these friends - play a

part in network

formation (Easley & Kleinberg 2010).Nevertheless, “a social

network exists

only if the users gain from cooperation and have the incentives to

interact

with one another. Therefore, to understand the necessary conditions for

the

formation of media-sharing social networks, we must investigate when

and how

users collaborate.” (Zhao et al 2011:167).

Due

to the membership of many

media-sharing social networks being voluntary and unregulated, the

‘connectivity’ or degree of connection between the

multiplicity of

communication networks can be varied (Kluitenberg 2006).The

users’ cooperation

cannot be guaranteed, giving rise to potential strategies employed by

others to

encourage such cooperation (Zhao et al 2011). Without any explicit

attempt by

the user, neighbour-copying can still occur where the individual mimics

the

behaviour of the closest individual.In everyday decision-making an

information

cascade occurs when people observe the actions of others and then make

the same

choice that the others have made, independently of their own private

information signals.

Types

of social acts

Gillan

and Merchant (2013) define some of the key ways Twitter is used based

on their

dual autho-ethnography: citizen

journalism, political activism, maintaining a fan-base, event

back-channel,

corporate advertising, service marketing, crowd-sourcing, informal

social-networking, and ambient sociability (alone but communicating

with

friends). Murthy

stresses that activism needs strong ties not

weak ones and “Twitter is about loose networks of

‘followers’ rather than a

structured organisation with leadership” (Murthy

2013:101),although here he is

talking about large scale political movements rather than the social

media-organised publicity ‘flash mobs’ we might be

accustomed to in town

centres. A closer study of the‘Individual User – Tool

(Twitter) – Other User’

interface may contribute greatly to our understanding of the

possibilities for

this tool in social network formation and how individuals and

communities

collectively create meaning and make sense of the world around them.

The

role of twitter as a mediating

tool for social acts

Hybrid

network society and

invisible technology

Where

technology and communication

networks are interwoven with social and political functions, a

‘hybrid space’

is created (Kluitenberg 2006). However, the technology potentially

becomes

invisible as it disappears from people’s awareness, due to its

frequent use and

embedding in our everyday acts and the small and subtle appearance of

the

physical devices and the physical action required to control them.

Manovich

(2002) argues that spaces are continually enriched with technology, but

only

become activated or ‘augmented’ when a specific function is

required, for

example, one engages with other spaces through a wireless connection.

Nevertheless, this human action, although utilising the Web, will also

rely on

the importance of (occupying) physical space (Jurgenson, 2011: 86).

Heidegger

(1977) conceptualises

technology as a “man-made means to an end established by

man”. By

conceptualising the human-tool interface as operating in a hybrid

space, we are

moving towards an understanding of communication and public

‘voice’ not so much

objectively mediated by tools but as human social acts taking place in

the same

virtual reality space as the mundane and everyday acts that are shared

and

commented on by individuals and their ‘friends’. This

blurring of boundaries is

an important element to consider in studies of the nature of

interaction via

social media.

The

functions of Twitter and the user

interface

Twitter

is a micro-blogging service

that allows users to post updates of a maximum length of 140

characters, published

in reverse chronological order on their Twitter homepages. The posts -

‘Tweets’

- are intended as a response to the question “What’s

happening?” This public

response hints at a broader social commentary than its Facebook

counterpart

status update that asks “What are you doing?” or “How

are you feeling?” Twitter

can also be used to share photos and links to other sites, as a way of

disseminating information in other forms than the simple 140-character

Tweet.

The user is asked three basic to-dos. Tell us what you’re doing,

find some

friends and follow what they’re doing, and turn on your mobile

phone to update

your friends on the go. In general, Tweets can be seen by all users on

the

medium rather than being restricted to one’s friends - anyone can

instantly see

a Tweet and respond to it (Murthy 2013).

One does not need to ‘know’ the other user or have

their permission to

direct a Tweet at them, although optional anonymity and private

accounts are built

into the system.

|

Term |

Meaning |

|

@ /

at-mention |

DirectsTweets

to certain users |

|

DM /

direct message |

A private

Tweet between two individuals (not published) |

|

Follower |

Another

user who has elected to follow the user |

|

Hashtag |

Topic

classifier; # placed before any text means a user can link their

Tweetto a larger conversation on the same topic |

|

Profile |

Homepage

equivalent with user information, followers, following and published

Tweets |

|

Reply Tweet |

ATweet

which replies to another user(s) directly via @ |

|

RT /

Retweet |

ForwardedTweets,

written by others, viewable by followers. |

|

Timeline |

Real-time

display of all Tweets of user and those followed |

|

Trending

topics |

Most

popular hashtags at any time. |

|

Tweet |

A message;

restricted to 140 characters and publically available(even without

having a Twitter account) |

Table

1 –

Glossary of Twitter terms.

Perceiving

Tweets as mere

superficial chat does not take into account the human creativity that

takes

place when discussions and information are combined and shared by users

to create

new meaning (Murthy 2013). Sturken & Thomas (2004) draw our

attention to

the user’s own perceptions of the social media tool they are

using as being

relevant to the functioning of the tool:

People

assign symbolic meanings to technologies. The

messages we communicate about technology are reflective,

revealing as much about the communicators as they do

about the technology. (Sturken & Thomas 2004, cited in Baym 2010:23)

The

dialogue between Twitter users

occurs through the at-sign - @ - before another user’s profile

name to direct a

Tweet at someone specific. Tweets can also be categorised by a

‘hashtag’. Any

word(s) preceded by a hash sign - # - through which the post of

strangers are

linked together, becoming included into a larger

‘conversation’ consisting of

all Tweets with the same hashtag (Murthy 2013).The hashtagis a key

function in

the construction of networks, information cascade, and the possibility

for

collective social acts, as “conversations are created more

organically...the

discourse is not structured around directed communication between

identified

interactants. It is more of a stream, which is composed of a polyphony

of

voices all chiming in” (Murthy 2013: 3-4).

Also

important is the function of

the Retweet – the forwarding of Tweets written by others to

one’s followers.

Murthy (2013) notes that this action attributes the Tweet to the

retweeter,

embedding the post in their profile and clearly labelled as such with

the

letters RT. This has a bearing on the meaning created: the information

is not

only shared as in ‘passed along´but is given extra weight

or voice by being

posted by another, and is also attributed to that new individual with

their own

unique set of views, values, and

followers.

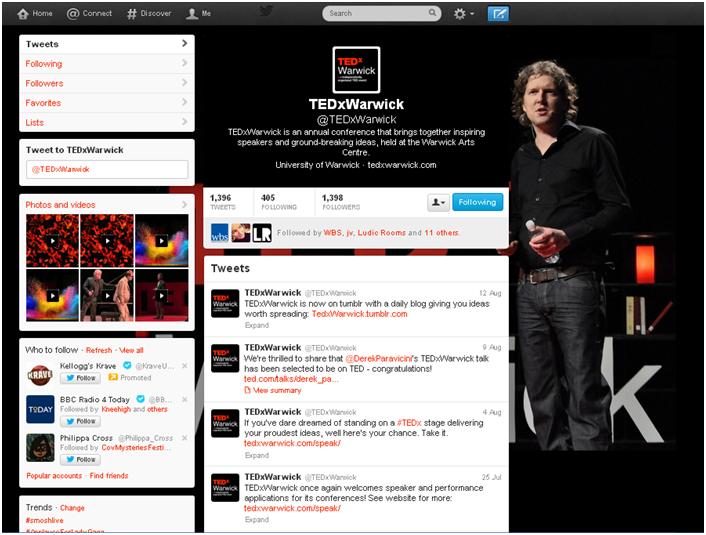

Figure

1 - The Twitter profile page

of TEDxWarwick, showing the use of @, #, and RT. Accessed 21/8/13

Awareness

of audience

There

is a stageat which individual

users progress from not only controlling a new interface such as

Twitter, to comprehending

the social dimension inscribed in and enabled by its interface (Herwig

2009).Given

the public reach of Twitter, it is not just the actual number of

followers but

the user’s own perception of the anonymous others that may read

and even

retweet their original content that has a bearing on their sense of

wider

audience and agency in having a public voice. This is compared

toFacebook where

the user’s number of friends “provides material evidence

for the success and

status of that user’s constructed identity” (Charles

2012:123). Twitter

networks often formed around an event of particular interest, such as a

TV

talent show or a sports match, where the stars are ‘spoken

to’ by the ordinary

user or the broadcaster highlights pertinent content. Here it is

possible to

cross a boundary and make visible and physical what is usually only

virtual as

a form of ‘telepresence’ – a term attributed to

Minsky (1980) the founder of

MIT’s artificial intelligence laboratory, which refers to the

user’s perception

that they are interacting with other humans as if in the same space.

Methodological

approaches for

research in tracking and analysing social acts via twitter

Generating

data from Twitter

Tweets

can be analysed in two

distinct ways: firstly, Tweets can be analysed as individual objects

with word

and function content, such as Kouloumpis et al (2011), who found that

the

Twitter features – hashtags, emoticons, and intensifiers (such as

exclamation

marks) – were more useful than the word content in tracking

sentiment. Secondly

they can be analysed as objects that are taken up by another user

– either by

retweeting or the adoption of hashtags.

A

number of large scale studies

have taken place over the last few years, and whilst their results are

perhaps not

dramatically different to what one might expect, they provide important

evidence and tested methodological approaches for future research in

this area.

Suh et al (2010) used

a dataset of 74 million Tweets

to identify factors associated with retweet rate, also building a

predictive

retweet model. They found that URLs and hashtags have strong

relationships with

‘retweetability’. Perhaps unsurprisingly the number of

followers, as well as

the age of the account, seems to affect retweetability, although the

number of

past Tweets does not predict retweetability of a user's Tweet.

Romero

et al (2011) collected over

3 billion messages over 6 months from more than 6 million users,

analysing

sources of variation in how the most widely-used hashtags on Twitter

spread

within its user population. They found that sources of variation in

hashtag use

“involve not just differences in the probability with which

something spreads

from one person to another...but also differences in a quantity that

can be

viewed as a kind of ‘persistence’, the relative extent to

which repeated

exposures to a piece of information continue to have significant

marginal

effects on its adoption.” (2011:1). Hashtags that were more

politically

controversial were particularly persistent, in contrast to those

created within

the Twitter conversational style of words joined together, such as

#itsalwaysme. Romero et al concludes by saying that “some of the

most

significant differences in hashtag adoption provide intriguing

confirmation of

sociological theories developed in the off-line world” (2011:8)

such as

‘complex contagion’, relating to repeated exposure to

ideas, particularly those

that are contentious. This is consistent with other research and

literature

that acknowledge the subjectivity and the motivation of the user,

influencing

their interaction with spaces, communities, and the tool itself. They

make

strong recommendations for further study including:

‘homophilly’ and

influencing behaviours across topics and categories; and a more

fine-grained

analysis of a population at the individual level to contribute more

detailed

user-level data to the emerging body of broader studies.

Our

pilotstudy

The

pilot study we report on here took these key points from the review of

literature and previous research studies as its starting point. We

specifically

aimed to explore how network links are created and reinforced at a more

detailed user level, namely:

·

How

Tweets function as public social

acts in hybrid (on and offline) spaces

·

How

information propagates between

smaller communities of users across a wider network

·

How

computational analysis can be used

to model hybrid (human-technology) social networks

The

research required an interdisciplinary approach in its methodology.

Operating

from a new user account, we created the hashtag ‘#wj25’that

when used on a

designated day, would allow a Tweet to be projected onto a giant public

screen

in a main campus thoroughfare. The giant screen was situated just

behind an

outdoor performance venue during the Student Arts Festival. The hashtag

and

screen combined to offer an incentive for participants to post as well

as

explore notions of wider public audience. The hashtag also gave a

single

indicator for gathering Tweets relevant to the ‘event’ (the

live screen).

Mapping

Social Networks

Online

Social Networks are

particularly suited to computational modelling as the users and

communication

between them can be readily captured and analysed.

Such an analysis can be split into two parts,

structure and information flow, but the two are intrinsically linked.

The

principal idea behind analysing the structure of an Online Social

Network is to

identify the shape of the network; that is, to identify the users and

the

connections between them. In the case of Twitter this could look at

followers

and direct messages.

Once

the shape and layout of the

network has been identified, subsequent analysis can go in a number of

directions. One analysis would be to identify sub-groupings or

‘communities’ of

users. We define ‘communities’ as “groups

of related nodes that correspond to functional subunits such

as…social

spheres,” (Ahn et al 2010).

Furthermore, we are interested

insuch groups that have a large number of intra-connections but few

connections

to other sub-groups. A second form of analysis is to identify the

important

nodes in the network (see Tang et al 2010). In the case of Twitter this

could

help identify highly influential users: users whose Tweets reach a

large number

of people or who serves to transfer information from one sub-group to

another.

The

common abstraction in the

literature for analysing the flow of information and ideas is the

concept of

influence and idea adoption (Cosley et al 2010). A user in the network

is

exposed to a number of ideas and can either adopt an idea or not.

Additionally

each user is influenced by its neighbours and influences them in turn.

In the

case of Twitter, this form of analysis could be used to look at how

Retweets

propagate around a network or how the use of hashtags propagates over

time but

could additionally be extended to look at the actual content of the

Tweet for

particular words or meaning.

In

our pilot study, the architecture of the monitoring software was based

on a

client-server model with database storage. The server used the Twitter

streamingAPI to continuously search for Tweets containing

‘#wj25’. Each Tweet

was added to a moderation queue¸allowing a member of the team to

either publish

the Tweet or keep it hidden if it contained offensive content. Each

Tweet was

given a score depending on the number of hashtags (#), mentions (@) and

Retweets

(RT).

Every

14 seconds the two highest scoring Tweets were chosen for display based

on a

formula[1].

Whilst

the screen and Twitter feed was ‘live’, two members of the

research team

observed the actions of people in a thoroughfare space near the screen,

in

particular the Arts Festival performance area, and approached

individuals to

complete a survey questionnaire.

Using

a cross-discipline methodology, there a number of initial findings that

respond

to key areas identified in the literature: hybrid (people, technology,

and

event/place) spaces and telepresence; homophilly and network

connections; and different

types of activity.

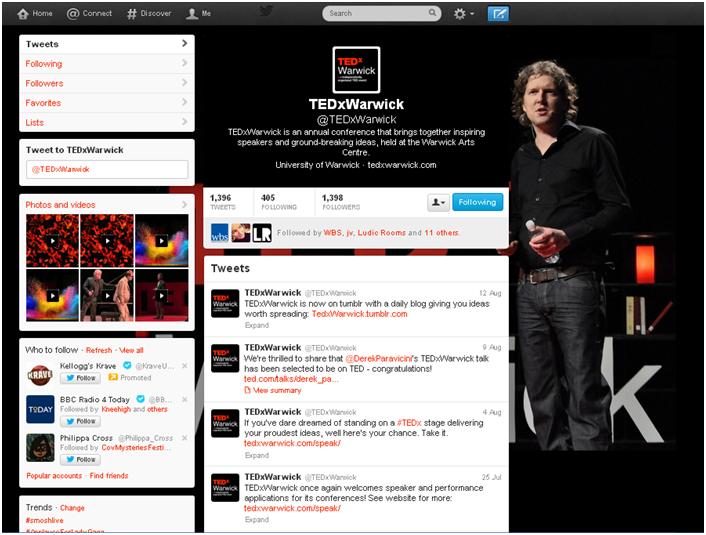

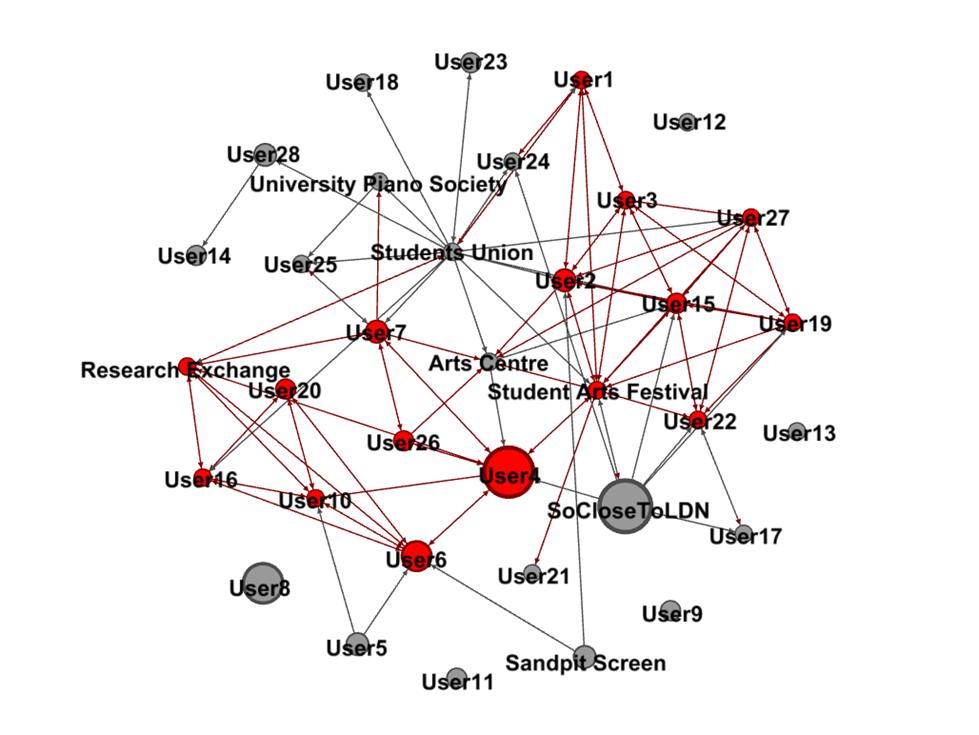

By

collecting Tweets and noting the followship of the participants in the

‘#wj25’

event, a database was constructed and used to recreate the network of

users

that emerged over the course of the event. The network data were

analysed using

the network analysis tool Gephi (Bastian 2009). Figure 2 shows a

projection of

this network data where nodes represent users and edges represent

followships.

Edges in the network diagrams in this paper are directed and the

direction of

an edge from User A to User B implies that User B follows User A. The

edge

directions can be seen as representing the way information (in the form

of

Tweets) flows from a user to their followers.

Figure

2. The #wj25 network map showing the users that tweeted during the

event and

the followships that connect them into a network.Although in the public domain, personal user

names have been anonymised in sensitivity rather than guaranteed

anonymity.

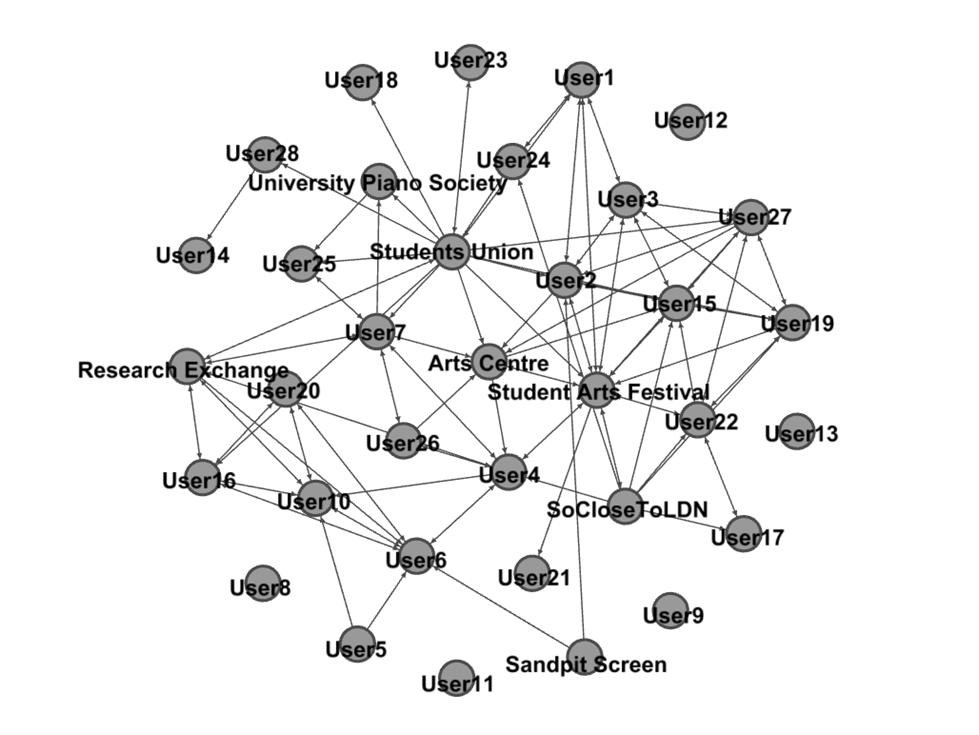

Figure

3 shows the network map with the nodes re-sized in proportion to the

number of Tweets

that the user made over the course of the event and re-coloured in

proportion

to the number of followers the user has. Larger nodes made more Tweets

and

nodes with higher colour saturation have more followers.

Figure

3. The #wj25 network map with node size representing tweet volume

(larger nodes

indicates more Tweets) and node saturation representing followers (more

saturation indicates more followers)

Although

small, this is a very connected network, with an unsurprising

followship

commonality to the Twitter account for the Arts Festival that research

event

was part of. However there are 5 users who participated that have no

connection

to other people in the network.

The

survey questionnaire generated supplementary information about this

network’s

general use of Twitter. Certainly not all those in the screen area were

Twitter

users and those who were used it to read news and information relating

to

others, which they did 2 or 3 times as much as posting themselves.

Therefore

the online network is a small subset of those who would have seen the

screen

and projected posts since there were significant numbers of people in

the

thoroughfare who were not necessarily avid users of Twitter.

As

well as looking at followers and tweets, we examined the number of

triangles in

the graph. Eckmann and Moses (2002) define a triangle as a set of three

users

where each user in the triangle follows both of the others. The number

of

triangles is responsible for many phenomena, including the rapid (high

number

of triangles) or slow (low number of triangles) information propagation

in a network

(Eckmann and Moses 2002, Easley and Kleinberg 2010). In the case of

Twitter in

particular, the formation of a triangle guarantees higher information

exposure

since a reply from one user to another is displayed to the third user

of the

triangle as well. Therefore, the formation of triangles is a crucial

parameter

in the information exposure of the network and the analysis of our

graph.

For

the network of active users in the #wj25 network we are able to

generate the

data in Table 2. These measurements show that a significant subset of

the

active users are not only linked to one another, but also participate

in and

form more complex structures, such as triangles. Figure 4 shows the

network map

with users in triangles coloured red with the size of the node

representing the

number of Tweets.

|

Total active users |

35 |

|

Mutual Followships |

84 |

|

Users in a triangle |

16 |

|

Total triangles |

41 |

Table

2. Statistics of user

triangle formation for the #wj25 network.

Figure

4. The #wj25 network map showing users in triangles (red colour) and

their

tweet volume (size)

The

proportion of active users in triangles in this dataset may be linked

to the

formation of social, physical, ‘communities’–

such as student arts performers - and participation level of the

(active) users

during the event (Eckmann and Moses, 2002). Indeed, it can be seen from

Figure 4

that some of the more active tweeters are part of a network of

triangles, but

this is not universally the case.

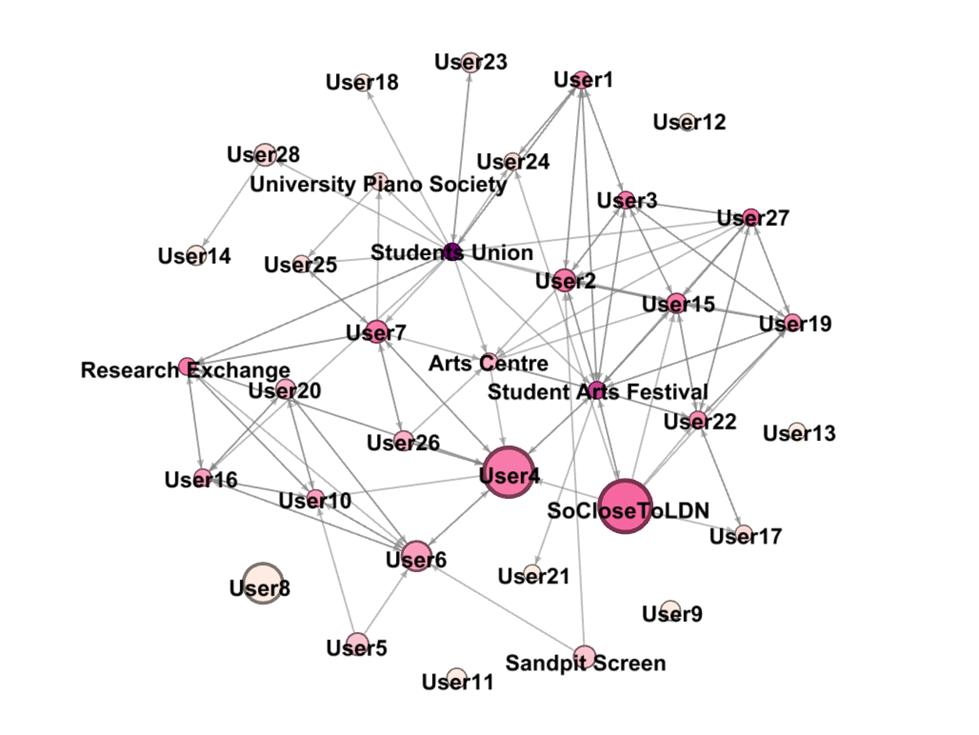

The

Screen additionally mimicked the use of a hashtag for juxtaposing

comments

relating to a particular event or tangible object, in this case the

thoroughfare

that the screen and some performance events were situated in and the

Arts

Festival as a whole. In the first instance, this connects users from

disparate

or related communities, revealed if we establish membership identities

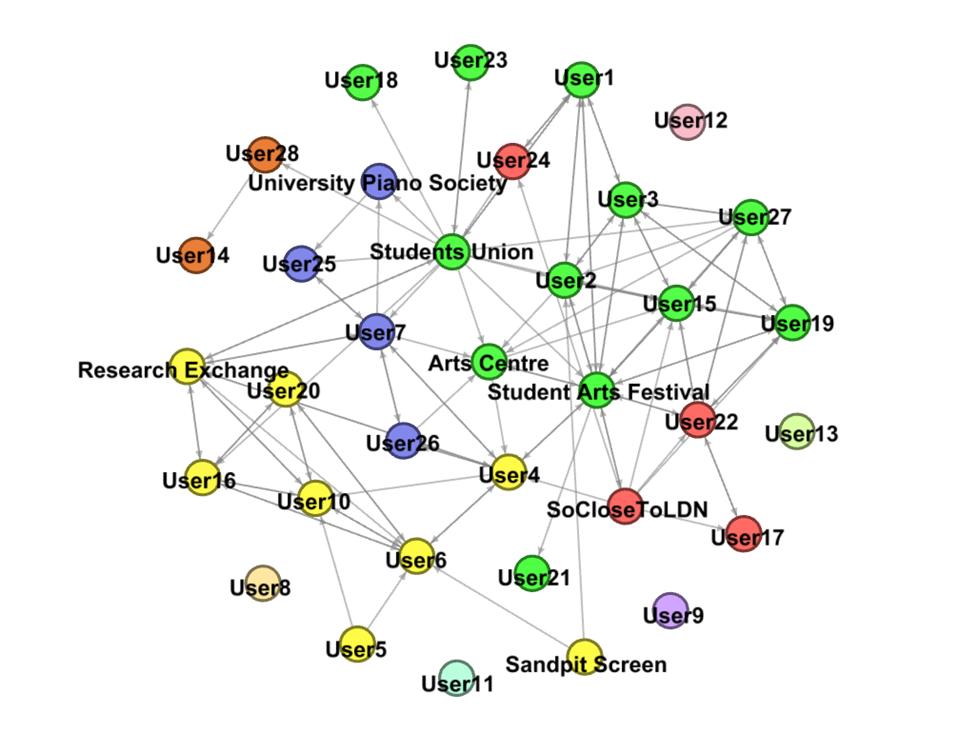

within

the network.An analysis of the network map using the algorithm

developed by

Lambiotte et al (2009) splits the network

into local communities based on the connections between neighbouring

nodes.

Applying this algorithm to the #wj25 network reveals a number of

different communities

within the network as shown in Figure 5:

Figure

5.

Communities discovered in the #wj25 network map. Four principal

communities are

identified (Yellow, Green, Red and Blue) along with one pairing (Brown)

and

independent users (pale)

Projecting

the Tweets on the giant screen mimicked the function of Twitter in

sharing

information and opinions with wider audience and followers. From

cross-referencing the survey data and an analysis of the individual

Tweet

content different types of activity can be identified.

Tweets

are mostly consistent with the user’s principal community,

supporting the

hypothesis regarding homophily – that the connections and social

acts made

through this online medium is related to the real world similarities of

interest and engagement. This is a small sample and further research

with a

larger data set may benefit from investigating this further.

Nevertheless, we

have identified clear communities within our network.As depicted in

Figure 8, users

in yellow are closely associated with the research project and tended

to

promote the event. Those in blue are closely related to the University

as staff

or societies, their Tweets tending to be marketing or commentary of

events.

Green is the largest community, based around the Student Union and the

Student

Arts Festival, posting for and about events, with a wider community in

red formed

around the fringes, representing the SoCloseToLDN online event.

Some

users took the opportunity to promote the Student Arts Festival –

either with

straightforward ‘official’ information or from a more

personal perspective,

appreciating the event & general surroundings. Cross-referencing

with the

network map shows that individuals can be prompted to contribute to

this

marketing. This is the case with at least two users, who are not

closely

connected to the Student Arts Festival like others are, but still

promote it in

both objective/informative and subjective ways:

@User16

Great atmospher at tocil fields in #warwickuni #wj25(sic)

[13:14.06]

@User23

@sandpitscreen #wj25 put on your dancing shoes and come dance with us

at

Warwick Folk’s ceilidh at 5pm in the Atrium :D [15:06.01]

SoCloseToLDN – a separate online event where members of the public could send players around London to get photographs of locations – were also aware of the potential added value of the screen, adding #wj25 to their own posts to generate interest and increase their remote audience. This is also a good example of telepresence, in that the event allowed members of the public to be ‘virtually’ in London and that this presence was projected into the thoroughfare through the screen. Other individuals used #wj25, and therefore the screen, to increase the size of their own personal and social gesture, such as saying ‘hello’ to a friend or thanking a friend for a drink.

The

literature suggests that hashtag brings Tweets together as a

‘conversation’.

The positioning of the screen in the physical space and the fact that

it

provided a window into a virtual space prompted some interesting

interaction

modalities from the users. As one user stated, it was a “fun way

to interact

without face to face chat” (Questionnaire #9). Not all posts were

positive with

users seizing the opportunity variously to share their disappointment

that TV

coverage of a tennis tournament was not being screened; deplore the

waste of

money that the Screen symbolised; and, for outlier @User11, to

criticise the

music of an outdoor concert in front of the Screen.

@User27 is an interesting example. Figure 5

shows him as part of the Student Arts Festival community, and is a user

with

many followers who tweets frequently in his daily life (see Figure 4).

On his

Twitter homepage he defines himself as an arts critic as well as a

social

critic, suggested by his background image of a recent on-campus

protest. Instead

of joining the others in marketing and personal positive promotion of

the work

of his community he instead chooses to criticise the University by his

negative

comments about the Screen. He purposefully uses the Screen itself to

further

publicise his own comment, enabling him to physically inhabit the very

space he

is challenging.

There

were also some examples of users communicating in a truly hybrid way,

interacting both with the Twitter space and the physical space through

the

medium of the screen. In these interactions information and messages

are

present on the Twitter network and also on the screen allowing people

who are

not connected to each other to see what others are posting and reply.

The game

of ‘I Spy’ started by @User8 and the photograph taking

interactions centred

around @User28 (covered below as case studies) are both examples of

information

flow in a truly hybrid space.

@User28

is an interesting example of interplay and the potential for a ripple

effect in

social behaviour. He was sat in a bar near

the screen but only became engaged when he saw another person taking a

photograph. He paid more attention to the projected text and made his

first

post:

@User28

Just want to see if this will show up #wj25

[18:46.39]

It

did, which prompted him to then take a photo of his own post on the

screen. One

of the research team, @User6, noticed his desire to interact with the

screen

and built on @User28’s own creative response, posting –

from his own Twitter

account – a photo of the photo; a playful interchange which was

reciprocated,

along with a personal recognition of the other users through the @ and

a

connection with a particular real-world community, the University

Photography Society:

Figure

6. The interplay on the

screen and the photo of a photo. This image is from the user’s

Twitter website

homepage.

Here

we have a physical act prompting a virtual act into a dialogue between

users

who do not follow one another. Eventually, another of @User28’s

followers also

joins in, trying to start a quiz. Unfortunately this was just before

the screen

was switched off and so we were unable to track subsequent acts:

@User14

@SandpitScreen #wj25 let’s play a game! Q – What turns in

to ice faster, hot or

cold water? Tweet answer to @SandpitScreen with #wj25

[19:45.39]

@User8

is another interesting case. From the network graphs it is evident that

he is

unconnected in terms of inner communities but tweeted a lot. From his

questionnaire we know that he particularly enjoys this kind of

interactive

event and posted a short farewell to the University with a sad face

emoticon in

the evening (it was the end of his last year as a student). Early on he

initiates a game of ‘I Spy’ and manages to bring several

other users in the physical

space into the interchange. It is a particular type of dialogue as its

sustainability depends not just on people using the hashtag but also

entering

content that plays within known rules. Rather than for an online

audience it is

designed for people who are occupying the same physical space and may

guess appropriately

(although that is not to say that others elsewhere could not). Even so,

within

the designs of the onscreen ‘game’, unless followers of

participating users

picked up on it and retweeted, the game would not extend very far

outside of

the immediate physical – and online – group of people.

@User8 as the originator

also gave himself particular power as he supposedly knew and could see

the

answer – in actual fact he did not start off with an answer in

mind and was

waiting for the most interesting response, exploiting his physical

anonymity. From this small case we can

see how an individual can become engaged and initiate social acts in

others

even from outlying community position. There is perhaps some attempt at

inflation of personal or social status through the use of this social

media

platform that may be worth considering in other Twitter-based research.

In

contrast to the previous two users, @SoCloseToLDN, operating

the London

based Virtual Tourist experience (Red in Figure 8), is well connected,

although

also peripheral, to the largest

community (Green in Figure 8). The userrepeatedly used #wj25 in order

to

increase audience awareness of their eventbut very few of their

associated

users did when they retweeted posts. Working on the same premise as

‘I Spy’ - that

sustainability and growth requires an investment of posts by followers

-we

assume that SoCloseToLDN’s followers were unaware of the

potential power of the

screen and of the hashtag. This is a reminder that simple opportunities

to

reach a wider audience via Twitter are not fully understood or

exploited for

whatever reason; therefore the social act does not reach the full

potential of its

impact.

Recent

literature and research highlights a need for studies that consider the

spread

of information and creation of networks across social media within a

given

temporal and spatial frame, capable of analysing at both individual and

community levels. Along with an exploration of suitable methods of

computational modelling and integrated qualitative data, such studies

will

contribute to developing our understandings of our network society. Throughout

the findings of the pilot study presented in this paper we have

provided a rich

analysis of the way in which people used Twitter and the hybrid space

through

the course of the #wj25 event.

By

combining a data-driven, network

analysis approach with a sociologically driven qualitative analysis it

is

possible to derive a deeper insight into the operation of a hybrid

network than

is possible through using one approach in isolation. We believe that

closer

studies of the Individual User – Tool (Twitter) - Other User

interface can

contribute greatly to our understanding of the possibilities for

Twitter in

social network formation and collective meaning making as users

continue to

interact with the world around them on a daily basis.

In

our analysed network, Tweets operated as objective and subjective

social acts

that promoted ideas and events, as well as made personal social

gestures. Users

subconsciously and consciously operated in a hybrid space, using the

physical

presence of the giant screen to initiate playful dialogues and power

shifts,

and to entice others as active users into the social network.

By

finding an effective way of mapping the social networkwe were able to

begin to

reveal itslevel of connectedness, and information flow through a number

of smaller

communities, as well as give a sense of more complex triangular

relationships

and homophily. This

approach, as recommended by Romero

et al (2011), has provided an analysis of the users at an individual

level

whilst also considering their place in the overall network structure.

It sits

well beside the many quantitative, impersonal approaches taken in much

of the literature

and could be expanded towards other larger studies.

Ahlqvist,

T., Bäck, A., Halonen, M. & Heinonen, S. (2008) Social Media

Roadmaps:

Exploring the futures triggered by social media, VTT Technical Research

Centre

of Finland. Accessed online 30/4/2013 at

http://www.vtt.fi/inf/pdf/tiedotteet/2008/T2454.pdf?q=sociable-media

Ahn,

Y., Bagrow, J., and Lehmann, S. (2010) Link communities reveal

multiscale

complexity in networks. Nature 466

(05 August 2010), pp.761-764

Bastian M.,

Heymann S., Jacomy M. (2009). Gephi:

an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks.International

AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media

Baym,

N (2010) Personal Connections in

the Digital Age, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press

Castells,

M. (2000) The Rise of the Network Society, Oxford: Blackwell

Charles,

A. (2012) Interactivity: New

media, politics and society, Oxford: Peter Lang

Cosley,

D., Huttenlocher, D., Kleinberg, J., Lan, X., and Suri, S. (2010) Sequential

Influence Models in Social Networks. In Proceedings of

the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and

Social Media, 2010, ICWSM

2010, Washington, DC, USA, May 23-26, 2010,

The AAAI Press.

de

Souza e

Silva, A.&Delacruz,

G.

(2006)Hybrid

Reality Games Reframed: Potential

Uses in Educational Contexts, Games

and Culture 1(3) pp. 231-251.

Easley,

D., & Kleinberg, J. (2010) Networks,

Crowds, and Markets, Cambridge: CUP

Eckmann,

J-P.&Moses, E. (2002) Curvature

of co-links uncovers hidden thematic layers in the world wide web. PNAS, 99(9):5825–5829, April 2002.

Gillen,

J. &

Merchant, G. (2013) Contact calls:Twitter as a dialogic, social, and

linguistic

practice, Language Sciences, Vol 35,

pp.47-58

Herwig,

J.

(2009) Liminality and Communitas in Social Media: The Case of Twitter.

Accessed

28/2/13 at

http://homepage.univie.ac.at/jana.herwig/PDF/herwig_ir10_liminalitycommunitastwitter_v5oct09.pdf

Heidegger,

M. (1977)The Question Concerning Technology

and

Other Essays by Martin Heidegger,

London: Harper & Row Publishers

Jurgenson,

N. (2011)When

Atoms Meet Bits: Social Media, the Mobile Web and Augmented Revolution,

Future

Internet, 4(1), 83-91

Kluitenberg,

E. (2006) The

Network of Wave: Living and Acting in a

Hybrid Space, Open Vol. 11, SKOR – Foundation for Art and Public

Domain.

Accessed online athttp://classic.skor.nl/2883/en/contents-open-11-hybrid-space,

28/2/13

, ,

& (2011) Twitter sentiment

analysis: The good the bad and the OMG, in Proceedings

of the Fifth

International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

Retrieved March 31, 2013, from http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM11/paper/view/2857/3251

Lambiotte,

R.,

Saramaki, J., and Blondel, V.D. (2009) Dynamics of latent voters. Physical Review E, 79(4):046107, 6

pages.

Manovich,

L. Lev

(2002) The Poetics of Augmented Space: Learning from Prada), Accessed

online

31/3/13 http://www.manovich.net/articles.php

Minsky,

M.

(1980) Telepresence, Omni, June 1980

Murthy,

D. (2013) Twitter: Social communication in

the Twitter Age, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press

Romero,

D., Meeder, B., Kleinberg, J. (2011) Differences in the Mechanics of

Information Diffusion Across Topics: Idioms, Political Hashtags, and

Complex

Contagion on Twitter, Proceedings of WWW’11 – the 20th

international

conference on World Wide Web, pp695-704 Accessed 31/3/13 at

http://www.cs.cornell.edu/home/kleinber/www11-hashtags.pdf

Sturken,

M.&

Thomas, D. (2004) Introduction: technological visions and the rhetoric

of the

new. In M. Sturken, D. Thomas & S. Ball-Rokeach (eds.)

Technological

Visions: The Hopes and Fears that Shape New Technologies, Philadelphia,

PA:

Temple University Press

Suh,

B., Hong, L.,

Pirolli, P., Chi, E. (2010) Want to be Retweeted? Large scale analytics

on

factors impacting Retweet in Titter Network, 2010 IEEE Second

International

Conference on Social Computing (Social Com), pp177-184

Tang,

J.. Musolesi,

M., Mascolo, C., Latora, V. ;

Nicosia, V., (2010) Analysing Information Flows and Key

Mediators

through Temporal Centrality Metrics, Proceedings

of the 3rd Workshop on Social Network

Systems (SNS'10),

ACM Press -

Association for Computing Machinery, pp1-6

Wellman

and

Berkowitz (eds.)(1988) Social Structures: A Network Approach,

Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press

Zhao,

H., Lin, W., Liu, K. (2011) Behavior

Dynamics in Media-Sharing Social Networks, Cambridge: CUP

Where Age

is the time in seconds since the creation of the Tweet, and Last

Appearance is the time in seconds

since it last appeared on the screen (or equal to Age

if the Tweet has not yet been displayed). R is the

number of times the Tweet has been retweeted. H and M are the number of hashtags and mentions contained in

the Tweet

respectively. The formula was designed to ensure that new Tweets had a

high

probability of being selected. The weights applied to R¸

H, and M were designed to encourage

engagement

with other users.