Abstract

This

article uncovers the relevance to

practice of behavioural and social determinant models of HIV prevention

among

Yoruba women in Nigeria. Exploring what factors influence health

behaviour in

heterosexual relationships, the key question raised was whether the

women’s

experiences support the assumptions and prescriptions for action of

these two

dominant public health models. Eight focus group discussions and 39

in-depth

interviews were conducted, which involved 121 women and men who were

chosen

purposefully and through self-nomination technique. This study revealed

that

the women were very much constrained by social environments in

negotiating safe

sex, despite having at least a basic knowledge of HIV prevention.

Limiting

factors included the fear of relationship breakup, economic dependence,

violence, and the difficulties in justifying why they feel the need to

insist

on condom use, especially since initiating condom use is antithetical

to trust.

Furthermore, evidence suggested that improved access to income and

education

might be vital but it does not automatically constitute a direct means

of

empowering women to prevent HIV infection. The limitations of both

behavioural

and social determinants perspectives thus suggests the need for a

combination

prevention model, which focuses on how social, behavioural and

biomedical

factors overlap in shaping health outcomes.

Keywords

HIV/AIDS

prevention, Yoruba women, Nigeria, social

determinants model, behavioural model

Introduction

In

Nigeria, 88 per cent of women and 94 per cent of men

have heard about HIV/AIDS (National Population Commission [NPC] and ICF

Macro,

2009). Despite this awareness, this country has the second largest

population

of infected people globally and women remain mostly disadvantaged and

susceptible (United Nations General Assembly Special Session, 2010).

After decades

of seeking answers to HIV problems, the challenges are still daunting

mainly

because of a lack of clarity about how to address the needs of

different

populations. The global response remains hampered as policy makers,

experts,

and donors continue to hold different views of how to achieve effective

interventions. To understand why current interventions have failed to

deliver

effective outcomes among Yoruba women in Nigeria, I explored the

factors that

make them more vulnerable, and whether the solutions lie in the two

dominant

but seemingly contrasting perspectives that shape HIV policies and

strategies,

as underpinned by a behavioural model (BM) and a social determinants

model

(SDM).

On

philosophical and scientific grounds, proponents of

SDM hold that social inequalities cause and closely mirror health

inequalities

within and between countries (Gupta et al., 2008; Marmot et

al.,

2008). This model deploys a ‘functional’ meaning of health

and illness that

portrays health inequalities a consequence of social hierarchies that

follow a

social gradient. Deriving its philosophical influence from the

principles of

social justice (Commission on Social Determinants of Health [CSDH],

2008;

Ruger, 2004), SDM is consistent with the theory of justice according to

Rawlsian

‘liberal’ model, which supports the need for socioeconomic

and political

restructuring that allows more fairness in the distribution of life

opportunities (Rawls, 1971). Additionally, the origin of SDM can be

traced to

social epidemiology, which studies how social environments shape the

distribution of health and illnesses among populations (Berkman and

Kawachi,

2000).

My

assessments of SDM in this article centre

particularly on the influential final

report of the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Social

Determinants

of Health, which gathered a mass of evidence about how social and

structural

factors constitute health inequalities within and between countries

(CSDH,

2008). One of the main assumptions is that unequal access to power,

income,

resources, and services, has significant negative implications for

health

choices, behaviour, and outcomes. Accordingly, SDM prescribes global

health

reforms that take into account circumstances in which people are born,

grow,

live, work and age, and how such circumstances influence their health

outcomes

(Wilkinson and Marmot, 2003; CSDH, 2008).

Sub

Saharan Africa (SSA), in particular, remains

disproportionately affected considering the global inequalities in HIV

incidence. In 2011, this region accounted for 69% of the global

population of

people with HIV/AIDS, 70% of HIV related deaths, and 80% of all people

with

both tuberculosis and HIV (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

[UNAIDS],

2012). In terms of gender distributions, women and girls are still

mostly

affected, accounting for 58% of the infected in this region and bearing

the

greatest burden of care (UNAIDS, 2012). In spite of this challenge, the

global

responses to HIV/AIDS still foster inequalities, as many observers have

noted.

Lisk (2010) explained that although the burden of HIV/AIDS is

concentrated in

developing countries of the South, the current global health system

still

favour resource rich countries of the North, not only in terms of

access to

treatment and funding, but also in relation to decision-making

authority within

key global institutions.

Unlike

SDM, which focuses on how socioeconomic and

political environments shape health outcomes, BM focuses on how

individuals

make calculated decisions about their health behaviour. Significantly

influenced by Skinner’s work on operant conditioning (Skinner,

1938), BM

attempts to make predictions about observable human health behaviour,

which

could be rigorously examined through scientific investigations.

Although there

are different strands of BM, they all share assumptions that support

individual

level interventions drawing on the argument that: (1) health behaviour

is a

matter of rational choices; (2) it is predictable based on

peoples’ knowledge

of the consequences of their actions and the degree to which they value

health

(Rimer and Glanz, 2005; Rosenstocket al., 1994; Fishbein, 2000;

Fishbein, 2008; Prochaskaet al., 2008). Accordingly, HIV

policies shaped

by BM are often sympathetic to public health communications designed to

heighten

people’s perception of their vulnerability to infection, and to

those that

raise awareness about the severity of AIDS and benefits of risk

reducing

behaviour (Blumberg, 2000).

Both

SDM and BM have drawn criticisms. According to

critics, SDM lacks a clear functional definition, which can translate

to

rigorous evaluations of health programmes that follow the prescriptions

of the

model (Moulin, 2008; Kim et al., 2008; Argemiaet al.

2012;

Navarro, 2009; Stevens, 2009; Bambra, et al., 2010). In

support, some

writers have argued that it is inaccurate to consider poverty or

socioeconomic

inequality a direct driver of HIV/AIDS (Shelton et al., 2005;

Gillespie et

al., 2007). Likewise, critics of BM have argued that it is narrow,

mechanistic, and only responding to a fraction of populations’

health needs by

failing to take into account causal pathways to health that have their

roots in

social, economic, legal, and political structures (Blas et al.,

2008;

Amaroet al., 2001). To contribute to this debate, I explore in

this

article whether the participants’ behaviour, in preventing

HIV/AIDS, supports

the assumptions and prescriptions for action of both models.

Methods

A

qualitative approach was the most appropriate in

conducting this study (Rubin and Rubin, 2012) because key to my

objectives was

the need to elicit data that were capable of detailing people’s

experiences and

practices in relation to HIV prevention (Power, 1998).

Ethnographic

method was used to explore how the participants make meanings of their

everyday

life (Fetterman, 1998) in heterosexual relationships. A pilot was

conducted,

which shaped the main investigation process. The study was conducted among Yoruba people in Osun

state, Nigeria, and data were obtained through

focus group

discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews (IDIs) (Rubin and Rubin,

2012;

Stewart et al., 2007). On average, each FGD took one and half

hours,

while an IDI took one hour. The investigation process involved digital

voice

recording and note taking. Altogether, there were 121 women and men

participants (see table 1 below), who were recruited from their houses,

market

places, religious, community and health centres, an academic

institution,

public offices, private business centres,

and

farm areas.

Purposeful

sampling and self-nomination technique were

used in selecting the participants because these methods allowed an

ethical

investigation process and efficient access (Dane, 1990). Given

the

criticism that selection techniques in qualitative studies are prone to

bias

because of over reliance on purposeful sampling (Watters and Biernacki,

1989),

I introduced stratification to the sampling process by dividing the

participants into six respondent groups. These included low and high

socioeconomic status women, low and high socioeconomic status men, HIV

positive

people, and local HIV prevention workers. With a clear definition of

eligibility for participating in each group, this approach supported

eliciting

data from samples that were representative of adult populations in the

study

area, in terms of gender, HIV/AIDS experiences, and socioeconomic

classifications. Those identified as low socioeconomic status

participants had

little or no education, and a low income. The high socioeconomic status

participants included those with at least a university degree and a

relatively

high income. Ages in all the groups ranged from 20 to 71.

Those

identified as HIV positive were recruited from a

HIV treatment centre and a local HIV organization. The selection

process was

self-nomination, in which individuals indicated their willingness to

participate. For ethical reasons, the participants in this group were

not

contacted until after they had given informed consent to participate.

The

officials at the centres organized the consent process. They were

specifically

told not to make people feel pushed to participate in the study

(Economic and

Social Research Council [ESRC], 2012).

All

the participants shared two characteristics; they were

in long-term heterosexual relationships and had at least a basic

knowledge of

HIV prevention. Because this was a sensitive study, with the potential

to cause

the participants harm or offense (Lee, 1999), and because of the

challenges of

obtaining permissions from gatekeepers (ESRC, 2012), no persons below

the age

of 18 were included. By explaining to them in detail the nature of this

study

and my responsibility to protect their confidentiality, all the

participants

were supported to make informed decision whether to participate or not

(Wiles et

al., 2006). The FGDs was conducted in enclosed spaces, which the

participants and I considered safe and suitable. A minivan was used as

a mobile

interviewing space for the IDIs. This strategy allowed effective

logistics and

privacy. Data analysis involved translating most of the data from

Yoruba to

English. After examining the transcript and identifying themes, which

had

emerged from the data, NVivo 8 was used in coding and categorising the

data

under different themes (Welsh, 2002). A limitation of this study might

be its

reliance on data obtained through self-reports, given that individuals

often

have the tendency to misreport their true experiences in sexual

relationships

(Mongkuoet al., 2010).

Results

and Discussion

To

present a clearer analysis of whether the women’s

experiences support SDM and BM, it is appropriate to present the

results and

discussion together. The participants are identified by the groups they

belong

to protect confidentiality: low status woman (LSW), high status woman

(HSW),

low status man (LSM), high status man (HSM), HIV positive (HP) and HIV

prevention worker (HPW). The analysis is divided into two main themes,

which

are social determinants of HIV/AIDS and behavioural determinants of

HIV/AIDS.

Social

determinants of HIV/AIDS

This

section indicates various social factors that shape

the behaviour of Yoruba women in relation to HIV prevention. These

factors are

categorised into seven sub-themes, which are; permanence of

relationships, trust,

economic dependence, fear of violence, religion and gender roles,

culture of

silence about sex, and desire for fertility. These factors are

discussed below.

Permanence

of relationships:

Discussing their views and experiences about sex in a regular

heterosexual

relationship, all the respondents indicated that a breakup is the most

likely

consequence if a woman attempts to exercise a greater degree of control

over

her sex life. This is a hidden factor, which writers rarely discuss in

HIV

literature and yet is capable of constraining women’s ability to

prevent HIV

infection. Because people place so much value on permanence of

relationships in

this society, women are socially constrained either in terms of

exercising

control over their sex lives or in deciding to leave a relationship

they

consider harmful. Discussing her experience, a LSW said that, ‘I

have never

tried to make independent decisions about my sexual and reproductive

life.’ Her

reason was that, ‘I do not think it’s wise for me to push

my husband to other

women, people will blame me.’ To exercise such control, she

suggested that her

society would consider her actions opposite to cultural expectations

about

women’s gender roles, which include satisfying partner’s

sexual preferences.

Most of the low status women indicated that they shared this experience

when

they said that, ‘it is difficult to initiate or insist on condom

use’ with

their partners, even when they had doubts about partner’s sexual

fidelity.

Given

that most of the low status women were economically

dependent on their partners, I initially held the view that they were

actually

concerned about the economic consequences of relationship breakup

rather than

worried about breakup itself. To understand the significance of this

social factor,

I investigated how it affects the behaviour of the high status women.

Evidence

showed that they were constrained in a similar manner even though they

seemed

to be economically independent. To experience a breakup is a serious

concern

for all the women because of the social implications. A HSW stated,

‘the Bible

says divorce is a sin,’ and thus suggested that she would avoid

any actions

that could lead to this, including exercising control over her sex

life, which

is necessary for women to reduce their vulnerability to HIV infection.

Besides

religious factors, relationship breakups often attract undesirable

labelling in

this society, as another HSW said:

Even

as a university lecturer, I cannot say that I have

control over my sex life. You know people would scare you when they

say, “look

at that professor, she was left by her husband because she was

demanding gender

equality.” This is how people stigmatise divorced women in our

society.

Sharing

her experience, a HSW corroborated the earlier

comments. She had separated from her husband because, ‘he wanted

me to accept

his infidelity as something normal for men and was therefore exposing

me to HIV

infection.’ She explained that, ‘our relatives and friends

criticised and

mistreated me for taking this action.’ While justifying her

action, she said,

‘this is a very difficult path to take but we must make our

society accept that

women should not be compelled to stay in relationships that endanger

their

lives.’ Unable to do the same, another HSW stated that she knew

the danger of

unsafe sex. However, ‘there are many girls out there who are

ready to do

whatever men want, so why should I drive mine away’ by trying to

insist on

condom use. These women did not suggest to me that they feared

relationship

breakups more than the risks of HIV infection. However, their comments

illustrate that social values and traditions are capable of

constraining women

in their efforts to prevent HIV/AIDS. This evidence is consistent with

SDM by

suggesting that it is inaccurate to limit women’s sexual health

behaviour to a

rational choice perspective, as it is the case that social environments

often

play a major role in shaping their behaviour. Because of her limitation

in

exercising a greater degree of control over her sex life, a LSW said

that, ‘all

I can do is to trust that he would not bring any disease to me.’

Trust:

This emerged as another

key social factor that constrains the ability of Yoruba women to

undertake

risk-reducing behaviour. The social context in this society encourages

partners

in monogamous marital relationships to have shared expectations about

trust

unless there is concrete evidence of unfaithfulness. Such expectations,

however, have serious implications for HIV transmission and infection

in terms

of fostering false hope about individual’s vulnerability (Bowleg et

al.,

2000; Sobo, 1995). For example, A LSM said that, ‘I do not use

condoms if I

trust a woman.’ In addition, all the participants who were

identified as HIV

free expressed that they would normally expect their partners to

consider

unprotected sex with them a risk free practice. For that reason, most

of them

said that they would construe condom initiation by a long-term partner

as an

indication of concerns about their HIV status. However, unlike men,

onus is

usually on women to justify why they feel the need to avoid unprotected

sex.

The acceptable justification is to provide concrete evidence that

support

claims. Because it is difficult to obtain such evidence, women in this

society

are vulnerable to HIV infection, a HSW indicated:

No

matter how empowered we are as women, and how

skilfully we can negotiate, it is not easy to insist on condom use,

even when

we think we are at risk. From my own experience, I know that men are

more

likely to deny having affairs but they expect us to trust them.

A

LSW agreed to the previous comment by saying that, ‘I

am faithful to my partner but I do not know what he does outside, so

there is

nothing I can do.’ This finding indicates the limitations of the

ABC

(Abstinence, Being Faithful, Condomise) strategy as underpinned by BM

of HIV

prevention. According to critics, this strategy has failed to take into

account

underlying contextual factors outside individuals’ control that

make monogamous

women in marital relationships vulnerable to infection(Murphy et al.,

2006).Sharing her personal experience, a HP woman illustrated how

expectations

about trust in sexual relationships could increase women’s

vulnerability to

HIV/AIDS: ‘My husband kept his HIV status secret from me until

his death. I

only saw his treatment card after his death.’ This woman

indicated that she was

faithful to her partner. However, she was infected because of trust and

lack of

concrete evidence that HIV infection was imminent by having unprotected

sex

with him.

Supported

by findings from this study, literature has

shown that 81 percent of women in Nigeria would refuse sexual

relationships

with a partner known to have sexually transmittable infections (NPC and

ICF

Macro, 2009). This implies that encouraging partners in long-term

relationships

to test and disclose status can give women the real empowerment to

prevent HIV.

A LSW said that, ‘no matter what the consequences might be, if I

know that my

husband has HIV, I will insist that he uses condoms before having sex

with me.’

She added that, ‘if he refuses, I will never allow him to sleep

with me.’

Sharing a similar view, a HSW stated, ‘If I have compelling

evidence that my

husband has HIV, I will be very serious about keeping myself

safe.’ These

comments seem to support the assumptions of BM that people would

undertake

recommended behaviour if they understand the severity of a health

problem and

value health (Glanzet al., 2002). However, the problem is that

these

women also indicated that they were unlikely to insist on condom use

based on

suspicion alone. Thus, vulnerable individuals could be at risk for as

long as

they are unable to prove that their partners are exposing them to HIV

infection. The main point therefore is that conformity to social

expectations

can be a risk factor, especially regarding the issue of trust in sexual

relationships. This finding raises questions about whether HIV

prevention

programmes should support the culture of suspicion as part of the

strategy to

encourage women to anticipate risks. This would require extensive

research to

understand the wider implications for women’s wellbeing.

Economic

dependence:

Evidence also emerged that this factor was a concern shared by all the

low

status women, and possibly the most significant constraining factor. As

a LSW

indicated, an attempt to exercise control over her sex life could lead

to

abandonment, in which ‘my husband could ask me to pack out of our

house.’ While

reflecting on the possible economic implications, she said that,

‘I would not

be able to cope on my own,’ dealing with her financial needs and

those of her

children. George and Jaswal in a study of low income women in India (as

cited

in Gupta, 2002) have indicated that disadvantaged women are more likely

to be

worried about the economic implications of leaving a relationship that

they

consider harmful than the health risks of staying in such a

relationship.

Corroborating

this evidence, most of the men in this

study indicated that they would normally exploit their position as the

breadwinner to force their sexual preferences on their partners. While

they

concurred that, ‘decision making is men’s

prerogative’, they also considered

the sharing of power and control with women in sexual relationships

unacceptable. A HSM added, ‘No, my decisions would always

override her

decisions.’ Although economic empowerment might be crucial for

women to

exercise a greater degree of control over their sex lives,

investigations with

the high status women suggested that access to economic power does not

automatically constitute a direct means of empowering them to prevent

HIV/AIDS.

For example, a HSW said:

It

is difficult to insist on condom use but more

difficult to abstain from sex as a married woman. Although condom use

might be

the best mean to protect myself, this is only possible if my husband

agrees.

Supporting

the above comment which suggests that women

cannot be empowered unless men are involved, a HPW stated that,

‘100 percent of

our female clients said they could not insist on condom use when their

partners

refused.’ This finding raises caution about the assumptions of

SDM, which

suggests that improved access to power, income, resources, and

services, would

make a big difference to women’s health choices, behaviour, and

outcomes. It is

important that improved access to economic power is not mistaken as

empowerment. Instead, the focus should be on whether women are able to

use

their access to life opportunities to achieve substantive freedom and

control

over their lives (Sen, 2001), without the fear of consequences, such as

intimate partner violence, which is another major constraining factor.

Fear

of violence:

Violence against women is a violation of their human rights, which has

serious implications

for their health outcomes. For most of the women participants, being

resolute

about condom use in their sexual relationships is more likely to

attract

violence from partners. A LSW who had experienced such violence stated

that,

‘there would be trouble again if I tell my husband that I will

not allow him to

have sex with me unless he uses condoms.’ She recalled and said

that, ‘my

husband did not beat me because I asked him if he was having

affairs,’ but he

turned violent because, ‘I refused to have sex with him to

protect myself from

HIV.’ This woman indicated that her experience with violence is

such a strong

force that has been constraining her ability to make the right health

choices.

This finding weakens the rational choice assumptions of BM. Similarly,

a HSW in

her account indicated that there is a strong connection between gender

violence

and women’s inability to exercise control over their lives:

My

husband had abused me physically and this experience

has affected my political career. He did not want me in politics

because he was

concerned that I might have affairs with my colleagues. I secretly

joined a

political party without his permission. When he discovered, he beat me

badly.

After much pleading, he eventually allowed me to join again, although

with a

serious condition. I agreed to his condition that, “if I see you

having

affairs, I will send you out of this house.” This means that I

would be denied

access to our children and whatever assets we have both acquired. In

spite of

this condition, I am still restricted in my everyday life and this

prevents me

from participating effectively in political activities.

Religion

and gender roles:

All the participants indicated that their religious environment play a

significant role in shaping women’s sexual behaviour to fit with

men’s

preferences. A few women expressed strong desire for a change. A HSW

stated:

They

preach in mosques and churches that we should submit

to our husbands. They expect us to put up with unpleasant situations.

This is

unfair and I think we should be able to insist on our rights.

However,

many proposed a less aggressive alternative, as

a HSW said, ‘in Africa we are very religious, so I will keep

praying to God

that I want my husband to change but I cannot insist on condom

use.’ For many

women in a similar context, acceptance of male dominance, as their

religions

and tradition stipulate, is necessary to achieve a degree of meaningful

life

(Jewkes and Morrell, 2012). Comments from some of the men corroborate

the

indications that religious ideologies contribute to why women are

vulnerable to

HIV infection. A LSM said:

In

support of SDM, this finding indicates that HIV

programmes need to recognise the roles religious environments play in

shaping

women’s sexual behaviour. What is more, some of the women

indicated that they

had internalized such a religious ideology as they expressed the belief

that

gender equality in sexual relationships is a utopian concept,

‘God did not make

men and women equal,’ a HSW said. She added:

The

acceptance and internalization of such gender stereotype

would mean that many women in this society are unlikely to be willing

to defend

their rights to exercise control over their sex lives. Thus, HIV

programmes

targeting this society must be designed to recognise that women are

sometimes

both victims and active promoters of the gender inequality and other

cultural

practices that disadvantage women (Jewkes and Morrell, 2012; O'Connor

and

Drury, 1998; Shneider, 2004).

Culture

of silence about sex: This is a widely acceptable cultural

phenomenon

among the Yoruba people, which seems to weaken the prescriptions of BM

on HIV

prevention. BM is sympathetic to public discussions about sex and

condom use in

the form of health promotion. On the contrary, as influenced by the

culture of

silence about sex, most of the participants considered open discussions

about

sex offensive, immoral, and tantamount to fostering promiscuity and

reckless

sexual behaviour, especially among young people. A HSW said that,

The

participants did not only indicate that there was a

widespread belief that condoms equates with promiscuity or

unfaithfulness, they

also suggested that the possession of or public discussions about

condoms

attract social stigma. In view of that, they acknowledged that this

factor

contributes to why people avoid using condoms. According to a HSM,

‘I would

feel ashamed to go and buy condoms, even if I intended to use them with

my

wife.’ To reduce the stigma associated with the possession of

condoms, another

HSM stated that local names have been created for them, ‘fere

daddy’

(daddy’s balloon), ‘agbeojo (rain coat/umbrella),

and ‘kini yen’

(that thing). Yet there is widespread antipathy to explicit

communication about

sex and condoms because of the perception that it undermines their

tradition,

moral values, and religious principles. Literature has shown that women

and

girls are more disadvantaged by this culture of silence about sex (WHO,

2009).

Conformity to societal expectations means that they are more likely to

be

ignorant of basic information about sexual and reproductive health.

Therefore,

to achieve effective communications about HIV/AIDS programmes needs to

be more

sensitive to social and cultural elements.

Desire

for fertility:

This is another major factor, which contributes to HIV incidence among

Yoruba

women. In many African societies, having a biological child is an

important

phase of life. People regard this as a status symbol with high social

ranking

(Doyal and Anderson, 2005). To demonstrate their fecundity, in

conformity to societal

expectations, women of reproductive age unavoidably have to engage in

unprotected sex. As one the LSW stated, ‘It would be difficult

for me to insist

on condom use because I am trying to have a child.’ This

woman’s desire for

fertility means avoidance of condom use, which in turn, could increase

her

vulnerability to HIV infection, especially if her partner engages in

high-risk

behaviour (United Nations Secretariat, 2002). As an example of how

factors

outside women’s control influence their sexual behaviour, this

finding does not

support the assumptions of BM. Considering the findings above, it begs

the

question whether Yoruba women have the capacity to make free health

choices

about HIV prevention even though there are social and structural

barriers. This

statement is explored further in the following section.

Behavioural

determinants of HIV/AIDS

Discussions

in this section suggests that it is not

always that case Yoruba women are not capable of making free choices

about

their sexual behaviour, thus weakening the assumptions of SDM. In

addition, the

participants indicated the roles of biology in shaping sexual behaviour.

Condoms

avoidance to maximize sexual

satisfaction:

A study has indicated that consistent use of

condoms could deliver 80 percent reduction in HIV incidence (Wilkinson,

2002),

which means this is still the most effective approach to preventing

sexually

transmittable infection. However, ample evidence exists that many

people, women

and men, avoid using condoms because of the perception that they reduce

sexual

satisfaction (Higgins et al., 2010). In support of BM, findings

from

this study have also shown that avoidance of condoms is a calculated

choice

that many Yoruba people make to achieve undiminished sexual

satisfaction.

Discussing this issue, a LSM said that,

In

suggesting that his partner is an active player in

deciding whether to use condoms or not, this man’s comment

contrast with the

vulnerability perspective of SDM, which suggests that women’s

inability to

negotiate condom use is primarily a result of inequality in gender

power

relations (Higgins et al., 2010). Corroborating the evidence

that women

sometimes make free choices regarding condom use, a LSW said to me

that,

‘condoms have holes in them, therefore I think there is no point

using them if

they cannot guarantee a full protection.’ In this case, it is

reasonable to

argue, in support of BM, that access to accurate information about

condoms and

HIV prevention will encourage such a woman to engage in risk-reducing

behaviour.

Fear

of unwanted pregnancy:

More evidence emerged of how some of the women exercise control over

their sex

lives as a LSW stated that,

In this context, the use of condom seems to be synonymous

to birth control rather than a means to prevent sexually transmittable

infections. Nonetheless, it is important to note that this woman

indicated that

she was able to make free choices about her sex life. As such, her

comment

strengthens BM by implying that women sometimes play active roles in

deciding

whether to use condoms or not. Hence, it can be a difficult task to

ascertain

when structure or agency is dominant in shaping women’s sexual

health

behaviour. Besides behavioural and social determinants, the

participants

indicated that biology also play significant roles in shaping sexual

behaviour.

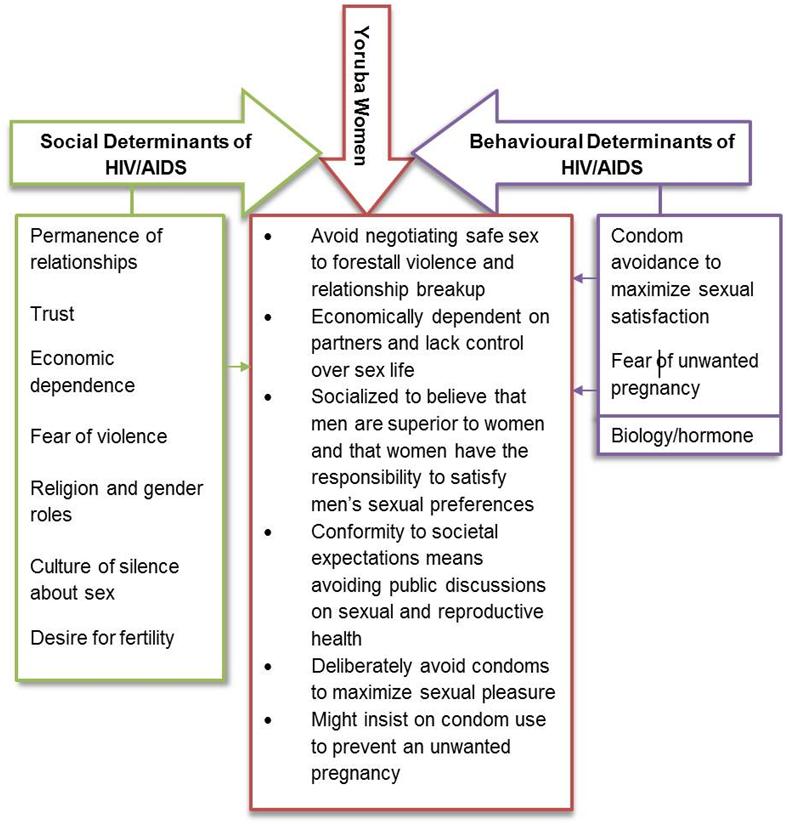

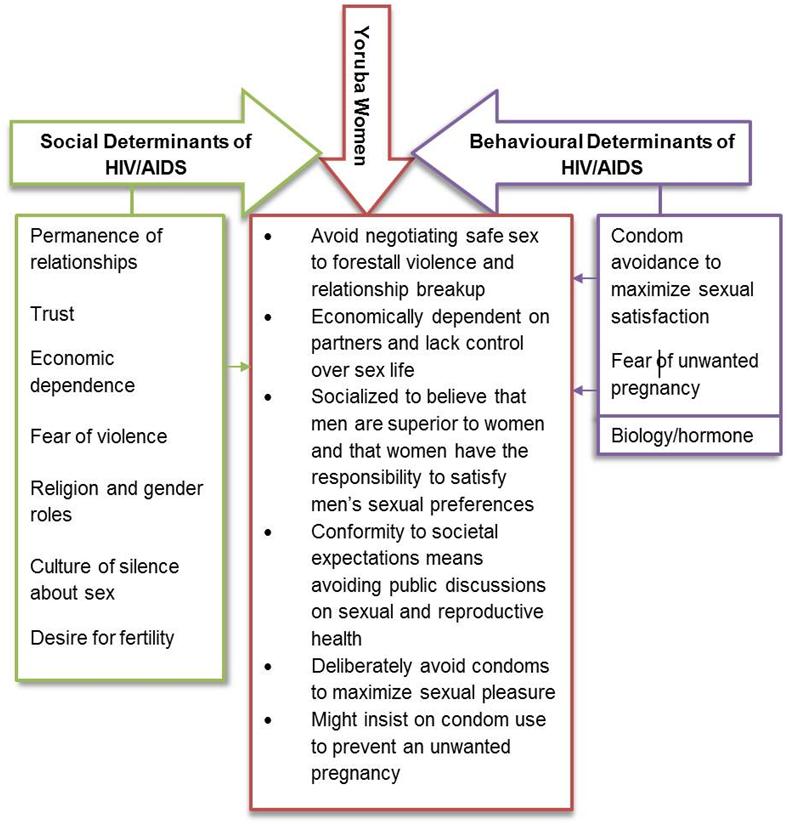

Figure

1: A Summary of the Findings

Human

biology and sex behaviour:

Some of the participants, men in particular, indicated that condom use

is not a

decision that they always have control over. According to a HSM,

‘the momentary

pressure experienced before a sexual intercourse does not give room for

negotiating condom use.’ Many of the participants intended to

suggest that

because of their biology, they often behave in an instinctive manner,

with

little or no control over their actions when sexually aroused. However,

because

this is a subjective experience, which varies between individuals, it

would be

difficult to measure the degree to which it is true that hormonal

pressure

limits individual’s ability to use condoms.

Old

age is another biological factor that some of the men

highlighted as a limitation in prevention HIV. Without a clinical

history of

erectile disorder, a 61 year old LSM said:

It

is normal for older men to have trouble with

erections. Without a sustainable erection, how could I use a condom?

The last

time I tried using one, I felt embarrassed as my partner watched me

struggling.

Before I could put it on, my thing [penis] became soft.

As

some of the participants have shown that condoms might

not be the appropriate method for HIV prevention among older men,

consequently,

it might be difficult for women to negotiate condom use with such men.

Conclusion

In

reference to the United Nations Millennium Development

Goals, there are worldwide acknowledgements that women in SSA need to

be

empowered to reduce their susceptibility to HIV/AIDS (United Nations,

2007).

The question remains, how could they be empowered? As illustrated in

this

article, the experiences of the Yoruba women have exposed the

limitations of

both BM and SDM, which means these models are not exclusively accurate

in

prescribing how to empower such women to prevent HIV/AIDS. Clearly,

access to

information and education is not enough. Despite having at least a

basic

knowledge of HIV prevention, most of the participants indicated that

their

sexual behaviour is inconsistent with this knowledge. Thus, it would be

inadequate to limit programmes to behavioural interventions. Likewise,

because

access to economic power and higher education did not seem to make a

big

difference among the high status women in negotiating safe sex with

partners,

the SDM is weakened.

Given

these limitations, it has been suggested that a

combination prevention model is a much better alternative (UNAIDS,

2010). This

approach requires a simultaneous use of complementary behavioural,

biomedical,

and social prevention strategies, while focusing on different levels of

interventions (individuals and groups), to address the specific but

diverse

needs of the populations at risk. In the context of Yoruba communities,

more

needs to be done in terms of providing access to accurate information

about HIV

prevention. However, because of poor infrastructure, rather than

concentrating

on conventional mass media programmes, more support should be given to

community workers to provide life skills tailored to the needs of

individual

groups in their communities. In addition, women need to be empowered,

but must

be supported to define clearly what empowerment means to them. Such

empowerment

should take into account factors such as: access to life chances

(education and

employment); participation in domestic and public decision making

process;

control over family assets; freedom of movement and association; legal

protection against injustice, discrimination, and harmful traditional

practices; and guaranteed access to state social

securities.

Lastly,

there is a case for saying that SDM and BM, as

they are currently, do not complement each other because they have

different

epistemological positions and commit to different policies. Hence,

further

research is required to understand how they could be developed to

complement

each other and the extent to which prominence should be given to either

in a

specific context.

Appendix

Distribution of Respondents

| Groups | IDIs | FGDs |

| Low status women | 6 | 1 (11 women) |

| High status women | 6 | 1 (11 women) |

| Low status men | 5 | 1 (10 men) |

| High status men | 5 | 1 (10 men) |

| Local HIV/AIDS agencies | 7 (4 women, 3 men) | None |

| HIV positive participants | 10 (6 women, 4 men) | 2 (10 women, 10 men) |

| Pilot studies | None | 2 (10 women in each) |

| Total | 39 (22 women, 17 men) | 8 (52 women, 30 men) |

Acknowledgements

The

author thanks Professor Mick Carpenter and Dr Phil

Mizen for their invaluable feedback on my PhD thesis, from which this

article

was drawn.

References

Amaro,

H. (2000), ‘On the margin: Power and women's HIV

risk reduction strategies’, Sex Roles,42 (7-8), pp.723-49.

Amaro,

H., A. Raj and E. Reed (2001), ‘Women’s sexual

health: the need for feminist analyses in public health in the decade

of

behaviour’, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25 (4),

pp.324–34.

Argemi,

X., S. Dara, S. You, J. Mattei, C. Courpotin, B. Simon,

Y. Hansmann, D. Christmann and N. Lefebvre (2012), ‘Impact

of malnutrition

and social determinants on survival of HIV-infected adults starting

antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings’, AIDS,

26 (9),

pp.1161–166,.

Bambra,

C., M. Gibson, A. Sowden, K. Wright, M. Whitehead

and M. Petticrew (2010), ‘Tackling the wider social determinants

of health and

health inequalities: Evidence from systematic reviews’, Journal

of

Epidemiology and Community Health, 64, pp.284-91.

Berkman,

L. and Kawachi, I. (2000), ‘A Historical

Framework for Social Epidemiology’, in Berkman, L. and Kawachi,

I. (eds), Social

epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.3-12.

Blas,

E., L. Gilson, M. Kelly, R. Labonté, J. Lapitan, C.

Muntaner, P. Ostlin, J. Popay, R. Sadana, G. Sen, T.

Schrecker

and Z. Vaghri (2008), ‘Addressing social determinants of

health

inequities: What can the state and civil society do?’, Lancet,372

(9650),pp.1684–9.

Blumberg,

S. (2000), ‘Guarding against threatening HIV

prevention messages: An information processing model’, Health

Education

&Behavior,27 (6), pp.780–95.

Bowleg,

L., F. Belgrave and C. Reisen (2000), ‘Gender

roles, power strategies, and precautionary sexual self-efficacy:

Implications

for Black and Latina women’s HIV/AIDS protective

behaviours’, Sex Role,42

(7-8),pp.613–35.

Commission

on Social Determinants of Health (2008), Closing

the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social

determinants of health, http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf,

accessed 10 September 2009.

Dane,F.

(1990), Research

Methods,California:Brooks/ColePublishing.

Doyal,

L. and J. Anderson (2005), ‘My fear is to fall in love

again...' How HIV-positive African women survive in London’. Social

Science

and Medicine, 60 (8), pp.1729-738.

Economic

and Social Research Council (2012), ESRC

Framework for Research Ethics (FRE) 2010 Updated September 2012, http://www.esrc.ac.uk/_images/Framework-for-Research-Ethics_tcm8-4586.pdf

, accessed 15 January 2013.

Fetterman,

D. (1998), Ethnography: Step by Step, Applied

Social Research Methods,Vol. 17, Thousand Oaks, California:

Sage

Publications.

Fishbein,

M. (2000), ‘The role of theory in HIV

prevention’, AIDS Care, 12 (3), pp.273-78 https://wiki.umn.edu/pub/EWB/UgandaCommunityHealth/The_role_of_theory_in_HIV_prevention.pdf,

accessed 14 May 2011.

Fishbein,

M. (2008), ‘A Reasoned Action Approach to

Health Promotion’, Medical Decision Making, 28 (6),

pp.834-44.

Gillespie,

S., S. Kadiyala and R. Greener (2007), ‘Is

poverty or wealth driving HIV transmission?’,AIDS, 21

(issue supplement

7), S5–S16.

Glanz,

K., B. Rimer and F. Lewis (2002), Health

Behaviour and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice.

California:

Jossey-Bass Publishers (originally published by the same publisher in

1990).

Gupta,

G. (2002), ‘How men's power over women fuels the

HIV epidemic’, British Medical Journal, 324 (7331),

183–84.

Gupta,

G., J. Parkhurst, J. Ogden, P. Aggleton and A.

Mahal (2008), ‘Structural approaches to HIV prevention’, Lancet,

372

(9640), 764-75.

Higgins,

J., S. Hoffman and S. Dworkin (2010),

‘Rethinking Gender, Heterosexual Men, and Women’s

Vulnerability to HIV/AIDS’, American

Journal of Public Health,100 (3), pp.435-45.

Jewkes,

R., K. Dunkle, M. Nduna and N. Shai

(2010), ‘Intimate

partner violence, relationship power inequity,

and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort

study’,

Lancet,376 (9734), pp.41–48.

Jewkes,

R. and R. Morrell (2012), ‘Sexuality and the

limits of agency among South African teenage women: Theorising

femininities and

their connections to HIV risk practices’, Social Science and

Medicine,

74 (11), pp.1729-737.

Joint

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (2010), Combination

HIV Prevention: Tailoring and Coordinating Biomedical, Behavioural and

Structural Strategies to Reduce New HIV Infections: A UNAIDS Discussion

Paper.

http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/20111110_JC2007_Combination_Prevention_paper_en.pdf,

accessed 20 March 2011

Joint

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS(2012), Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic,http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf,

accessed 16 May 2013.

Kim,

J., P. Pronyk, T. Barnett and C. Watts (2008),

‘Exploring the role of economic empowerment in HIV

prevention’, AIDS, 22

(issue supplement 4), S57–S71.

Lee,

R. (1999), Doing research on sensitive topics,

London: Sage publications.

Lisk,

F. (2010), ‘Global Institutions and the HIV/AIDS

Epidemic: Responding to an international crisis’, London:

Routledge.

Maman,

S., J. Mbwambo, M. Hogan, G. Kilonzo, J. Campbell

and M. Sweat (2002), ‘HIV-1 Positive Women Report More Lifetime

Experience with

Violence: Findings from a Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Clinic

in

Dares Salaam, Tanzania’, American Journal of Public Health,92

(8),

pp.1331-337.

Marmot,

M., S. Friel, R. Bell, T. Houweling and S. Taylor

(2008), ‘Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through

action on the

social determinants of health’, Lancet, 372 (9650),

pp.1661–669.

Mongkuo,

M., R. Mushi and R. Thomas (2010), ‘Perception

of HIV/AIDS and socio-cognitive determinants of safe sex practices

among

college students attending a historically black college and university

in the

United States of America’, Journal of AIDS and HIV Research,

2 (3),

32-47.

Moulin,

A. (2008), The World Health Organization and

the Social Determinants of Health: Assessing Theory, Policy and

Practice, http://www.ucl.ac.uk/histmed/downloads/social_determinants/comments/wellcomewhocairo.pdf,

accessed 12 October 2010.

Murphy,

E., M. Greene, A. Mihailovic and P. Olupot-Olupot

(2006), ‘Was the “ABC” Approach (Abstinence, Being

Faithful, Using Condoms)

Responsible for Uganda's Decline in HIV?’, PLOS Medicine,

3 (9),

e379, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030379, http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030379,

accessed 24 June 2010.

Navarro,

V. (2009), ‘What we mean by social determinants

of health’, Global Health Promotion, 16 (1), pp.5-16.

National

Population Commission and ICF Macro, (2009), Nigeria

Demographic and Health Survey 2008: Key Findings.

Calverton,

Maryland: National Population Commission and ICF Macro, http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/SR173/SR173.pdf,

accessed 15 July 2012.

O'Connor,

F. and B. Drury (1998), The Female Face in

Patriarchy: Oppression as Culture, Michigan: State University

Press.

Power,

R. (1998), ‘The Role of Qualitative

Research in HIV/AIDS’, AIDS, 12 (7), 687-95,

Prochaska,

J., S. Butterworth, C. Redding, V. Burden, N.

Perrin, M. Leo, M. Flaherty-Robb and J. Prochaska (2008),

‘Initial efficacy of

MI, TTM tailoring and HRI’s with multiple behaviors for employee

health

promotion’, Preventive Medicine, 46 (3), pp.226-31.

Rawls,

J. (1971), A Theory of Justice, Cambridge,

Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Rimer,

B. and K. Glanz (2005), Theory at a Glance: A

Guide for Health Promotion Practice,National Institute of Health

(first

edition published in 1995) http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/theory.pdf,

accessed 04 July 2010.

Rosenstock,

I., V. Strecher and M. Becker (1994), ‘The

Health Belief Model and HIV risk behavior change’, in DiClemente,

R. and

Peterson, J. (eds.), Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of

behavioural

interventions, New York: Plenum Press, pp.5-24.

Rubin,

H. and I. Rubin (2012), Qualitative

Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, Los Angeles: Sage

Publications

(originally published by the same publisher in 1995).

Ruger,

J. (2004), ‘Ethics of the social determinants of

health’, Lancet, 364, 092–097.

Sen,

A. (2001), Development as Freedom, Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Shelton,

J., M. Cassell and J. Adetunji (2005), ‘Is

poverty or wealth at the root of HIV?’,Lancet, 366 (9491),

pp.1057-058.

Shneider,

D. (2004), The Psychology of Stereotyping,

New York: The Guilford Press.

Skinner,

B.F. (1938), Thebehavior of organisms: an

experimental analysis, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Sobo,

E. (1995), Choosing Unsafe Sex: AIDS Risk Denial

among Disadvantaged Women, Philadelphia, PA: University of

Pennsylvania

Press.

Stevens,

P. (2009), ‘Bias in WHO report on the social

determinants of health’, Lancet, 373 (9660), 298, doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60091-X.

Stewart,

D., P. Shamdasani and D. Rook (2007), Focus

Groups: Theory and practice, applied social research methods

series vol.

20, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc.

United

Nations (2007), Africa and the Millennium

Development Goals 2007 update, New York: United Nations, http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/docs/MDGafrica07.pdf,

accessed 16 May 2011.

United

Nations General Assembly Special Session (2010), Country

Progress Report: Nigeria. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/nigeria_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf

access 23 July 2011.

United

Nations Secretariat (2002), HIV/AIDS and

Fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Research Literature.Esa/P/Wp.174.

http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/fertilitysection/HIVAIDSPaperFertSect.pdf,

accessed 02 February 2011.

Watters,

J. and P. Biernacki (1989), ‘Targeted sampling: Options

for the study of hidden populations, Social Problems, 36 (4),

pp.416-30.

Welsh,

E. (2002), ‘Dealing with Data: Using NVivo in the

Qualitative Data Analysis Process. Forum: Qualitative Social

Research’,

3(2)

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0202260,

accessed 10 January 2012.

Wiles,

R., G. Crow, S. Heath and V. Charles (2006), ‘Anonymity

and Confidentiality’, Paper presented at the ESRC Research

Methods

Festival, University of Oxford, July 2006. http://www.ccsr.ac.uk/methods/festival/programme/aac/documents/anonandconfpaperRMF06.pdf,

accessed 11 June 2011.

Wilkinson,

D. (2002), Condom effectiveness in reducing

heterosexual HIV transmission: RHL commentary, The WHO Reproductive

Health

Library, Geneva: World Health Organization, http://apps.who.int/rhl/hiv_aids/dwcom/en/,

accessed 12 February 2011.

Wilkinson,

R. and M. Marmot (eds.) (2003), Social

determinants of health: The solid facts,World Health Organization, http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/98438/e81384.pdf,

accessed 21 May 2011.

World

Health Organization (2009), Gender inequalities

and HIV, http://www.who.int/gender/hiv_aids/en/

accessed 21 July 2011.