Exploring

the potential for student leadership to contribute to school

transformation

Malcolm

Groves (University of Warwick)

Abstract

This

paper reports preliminary findings from case study research in three

English

secondary schools where a new or recently appointed head has

incorporated

stakeholder engagement as a key part of their improvement strategy. In

each

school, developments initiated independently by each head in relation

to

student leadership are reported. These appear to be re-thinking the

boundaries

of current practice in relation to student voice, particularly with

respect to

developing the leadership role of students as agents of change and in

beginning

to extend that beyond the school into their communities.The research

focuses on

seeking to understand the processes of change in each case. The models

and

practices adopted by each head in implementing change are analysed and

the

effects of this experience, as reported by the students, are

considered.

Initial findings highlight factors that appear to contribute to

successful

developments, and the paper concludes with suggestions for further

research and

investigation to confirm this.

Keywords

Student

voice, student leadership, stakeholder engagement, school

transformation

Introduction

Students

have brought an energy that you never get from adults. They see the

change

agenda perfectly and they understand it fully…. (It) is having

an enormous

effect. This, I believe, is where the school will be transformed. You

will have

student leadership in the classroom and beyond the school as well.

Headteacher, Ashtree School, 26.7.11

The

origins of this paper lie in reflecting on that quotation from an

interview

with a secondary school headteacher in England. It opened up a new line

of

enquiry in my part-time doctorate research involving case studies

developed

over two years in three English secondary schools. Fieldwork was

conducted

between November 2010 and November 2012. Through it, I wanted to

examine more

closely the possible inter-connectedness of stakeholder engagement and

trust,

the role of school leaders, and the potential for impact on educational

outcomes.

The

three schools included within this study were selected because,

although

representing differing socio-economic contexts and at different stages

of

improvement in OFSTED terms, in each a recently appointed head had made

an

explicit commitment to develop stakeholder engagement as part of their

school

improvement strategy. This was the main reason for their

selection, rather

than typicality or random sampling.

Through

the interview quoted above, a new emphasis on understanding student

leadership

opened up in the second year of the research. This was not a direction

anticipated at the outset, but it became clear during the first year

that all

three heads had independently decided this was to be a significant

element in

their approach to change. I wanted to understand why, and what this

meant in

practice.

Rationale

I

have adopted the term student leadership to describe the focus of

enquiry

as this was the term most frequently used by all

three headteachers to describe what they said they were seeking to

develop. Yet

there is only a limited research literature around the phrase. What

there is

suggests it could

involve a spectrum of approaches, from

structured practices of elections and representations, through which

students

engage in formal decision-making, to less formal responses through

which

student leadership practices diffuse and extend beyond schools to

engage with

the community (Mertkan-Ozunlu and Mullan (2007), McGregor (2007),

Lilley

(2010)).

Moreover,

in much of the literature on school leadership, (e.g. Hallinger and

Heck 2003,

Leithwood and Riehl 2005, Hallinger 2011), the role of students as

leaders is

not discussed. This is also true of the literature on school

improvement. For

example, Bryk and Schneider (2002) identified three settings in which

relational trust acted as a force for improvement in schools; between

principal

and teacher, teacher and teacher, and between school professionals and

parents.

Day et al (2009) add two others; principal/teachers with support (non

teaching)

staff, and principals with external agencies (including schools).

Neither study

makes reference to students in this context, perhaps reinforcing,

whether

consciously or not, a view that school improvement is something done to

schools

(and by implication to students) by adults.

Similarly, the thrust

of government policy in England since 2010 has placed prime focus on

the role

of teachers and the importance of teaching (DfE 2010).

Notwithstanding

the above, there has been a more general research interest into what

has been

termed pupil, learner or student voice (Cook-Sather 2006). In

England, the work of Rudduck and colleagues emphasised listening to

student

voice, justifying this in terms of its potential for school improvement

(e.g.

Rudduck et al. 1996). However Ranson (2000) links student voice

fundamentally

to the idea of the school as a democratic community.

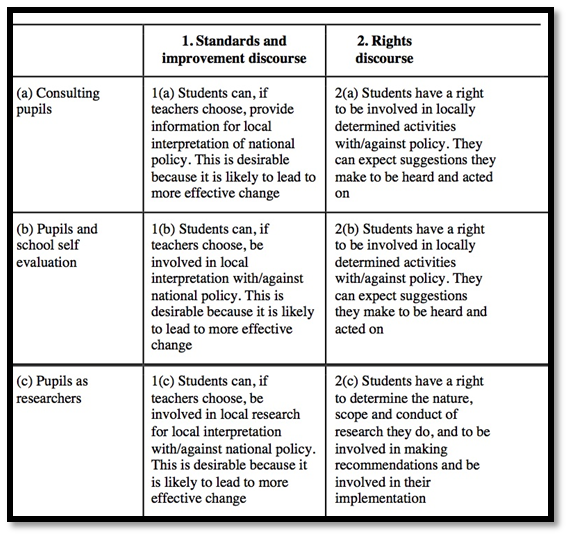

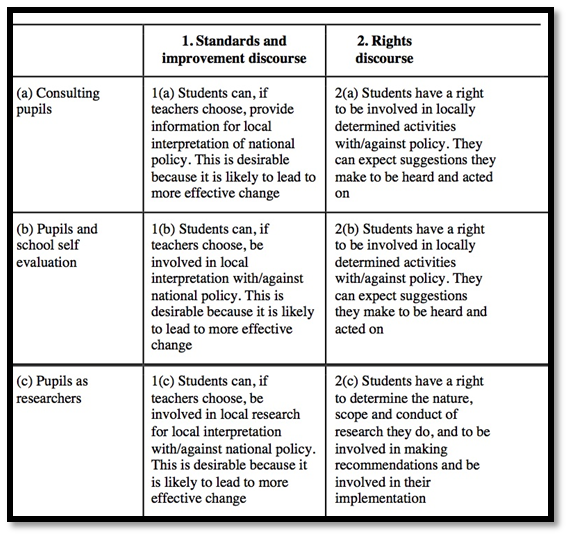

Thomson

and Gunter (2006) teased out facets of these two lines of discourse

about

student voice, capturing them in a matrix (Table 1).

Table

1: Analysis of understandings of student voice – Thomson and

Gunter (2006)

One

of the distinguishing features of this matrix, moving from left column

to

right, is an increasing transfer of power and responsibility from

teachers to

students. But for Thomson and Gunter this is contentious and

difficult

practice. They note particularly a number of inherent

tensions, one between extending choice to students whilst controlling

its

provision, another the tensions between the student as an individual

learner

and the student as a part of a social learning community.

Fielding

(2006) offers a four-fold typology for examining the way schools use

student

voice, relating it particularly to the functional and personal

dimensions of

their organisation. He then focuses on two of these responses in

particular.

These he terms ‘high-performing’, in which the personal is

used for the sake of

the functional, and ‘person-centred’, where the functional

is used for the sake

of the personal (p.302). His distinction is at root about a

school’s motivations

in adopting student voice, and whether this is done for particular

kinds of

adult purposes, for instance to enhance the school’s

effectiveness or

reputation, or whether it is to help young people develop as “good

persons”

(p. 307).

The

tensions suggested in both these accounts concern power, the way it is

used and

the purposes behind that use. There is an important sense in which some

tensions around the concept and practice of student voice are

inevitable, maybe

even desirable. Students are not the only stakeholders in their

schools. They

are also growing in maturity as they move through a school, as a

result, in

part, of what the school does. By definition they do not start - or

indeed

finish - schooling as a complete person. And schools also develop

and change,

as does the environment in which they have to work. What the literature

appears

to lack is a coherent account of the processes by which those tensions

may be

constructively reconciled and individual and organisational growth can

occur.

Student

leadership, as encountered in this research, still displays those

tensions to

some degree, but also appears to be finding ways, however rudimentary,

to move

beyond them. In all three schools, albeit in slightly different ways,

there

seems to be a genuine emphasis on students themselves becoming agents

of change

and, crucially, on understanding and developing the skills staff need

to

support this. In addition, the focus was at times moving beyond the

school to

include the influence students might have more widely in their

communities.

The

research

My

research focused on three questions related to stakeholder engagement,

and I

have applied the first two to the particular issue of student

leadership.

·

How

have heads sought to develop their vision of engagement strategy?

·

What

effects has this had?

·

What evidence is there

of its influence on educational outcomes?

Fernandez

(2004) suggested that a combination of case study and grounded theory

could be

particularly productive where three conditions (adapted from Benbasat

et al

(1987)) are met:

1. The research can study a

natural setting, learn the state of the art, and

generate theories from

practice.

2. The researcher can answer

questions that lead to an understanding

of

the nature and complexity of

the processes taking place.

3. It is to research a previously

little studied area.

These

insights informed the whole research design, and the conditions apply

equally

to the student leadership strand of enquiry. The research methodology

adopted a

programme of interviews with heads and other leaders, combined with a

series of

focus groups with staff, students and parents for triangulation so as

to ensure

the views of leaders were subject to wider validation. These interviews

were recorded,

transcribed and coded for meaning. In addition, surveys, designed

using

adaptation from the UK Social Capital Framework (Harper and Kelly 2003)

and

Goddard’s (2003) Social Capital Scale from America, attempted to

track

attitudinal change more widely. All were repeated across the two years.

In year

two, because of emerging findings, student interviews and focus groups

centred

on the role of student leaders. Each group of student leaders was

interviewed

at the beginning and end of the year, as was the member of staff

responsible

for this work.

The

three schools

Ashtree

School (all names are pseudonyms) serves a deprived, fragmented and

ill-defined

community on the outskirts of a large city. In the words of the head

(AH):

We

don’t have a village centre, or a set of shops, or a church, or

anything that

clearly defines community. Our parents and children don’t

have that in their

own lives either.

Ashtree

is a medium-sized 11-16 school. Most students are of White

British

heritage, but the number who speak English as an additional language

has been

increasing rapidly.

The

proportion of students with special educational needs and the

percentage known

to be eligible for free school meals are above average. There are very

high

levels of pupil mobility. Following

a long period of local authority concern, the school was re-launched

with a new

head and a new name in 2006. It is currently rated satisfactory under

the old

OFSTED Framework, but achievement is now rising and above floor targets.

Birchgrove

School serves a very different community. Built and opened in 2006 as a

new

town development, it does not yet have an established community. But

its intake

from around the city can broadly be described as middle class. Most

students are of White British heritage, with about a quarter from a

range of

minority ethnic backgrounds. The proportion of students with special

educational needs or disabilities is in line with the national average.

It

has grown every year since opening with just Y7-8 students, and now has

1500

students including post 16 provision.

The

present head (BH) came in 2009 and has moved the school towards

outstanding

under the old inspection criteria. It became a new-style academy in

2011. BH

was appointed with an awareness from governors of their need to improve

parental engagement, but he has since extended this to a much broader

concept

of community engagement based on a view about the competencies and

attributes

young people need to survive in a global economy in the future and how

they are

best developed. The development of student leadership is central to

this

vision.

Chestnut

Academy started from the lowest and most difficult base of the three.

It serves a predominantly white working class social

housing estate with high levels of unemployment and a poor local

reputation. The

academy was opened in September 2010 to replace one of the worst

performing

schools in the country in terms of examination results. Student numbers

had

dwindled to around 400, all aged 11-16 years.

A new head (CH) had been appointed from outside the

school and area the previous March, but to work with the existing staff

of the

old school, and, unbeknown to her at the time, a very significant

budget

deficit.

The

interim findings

In

this section each of the two main research questions relating to

student

leadership is considered in turn in the light of the case study

findings.

1.

How have

the three

heads sought to develop their vision of student leadership?

It

is clear that in each school it is the head who is the instigator and

champion

of the student leadership approach taken and the philosophy behind it.

This is

in line with the Australian findings of Lavery and Hine (2012), who see

the

role of the school principal as key to such development. Each

of the three heads in different ways sought to modify or fundamentally

change

existing practice in their school as part of their wider improvement

strategy.

In this they were all seeking to move beyond the basic model of a

school

council common in many schools. As

a result, each

school has adopted its own approach to student leadership, with both

similarities and differences, as shown in Table 2.

AH

decided in 2010 the existing school council was not working

effectively, and

replaced it with what was termed the student senate. Students chose to

apply

for the role of senate member, or were, in some cases, encouraged to

apply.

They are now appointed after interview jointly by staff and current

members.

However it was clear from their stories that it was not just what might

be

termed conforming or well-behaved students who came through this

process. A

number of those interviewed talked about past behaviour problems they

had been

helped to overcome. But it is certainly true that the number of

students

involved overall is relatively small, and also that they come from

Y7-Y10, as

the school felt exam pressures were too important, in the context of

the school’s

situation, for older students to be distracted by this work.

BH

had been working to increase the engagement of the existing school

council

which has representatives elected by each tutor group, albeit with

varying

degrees of enthusiasm. To this end, he involved council members in the

four

strategic staff working groups he had set up to support the school

strategic

plan put in place soon after he took up post. The four groups address

standards, innovation, personalisation and partnership.

In

this way BH looked to move student voice away from more peripheral

issues to

central areas of school development. An executive committee of older

students

now coordinates these groups overall and its members chair group

meetings.

Numbers involved are greater than at Ashtree, even allowing for the

size of

school, and BH is now keen to find ways to extend a much broader range

of

opportunities for leadership across the student body.

CH

in her first year adopted an inherited prefect system before rejecting

it and

replacing it with a new structure, the Student Academy Leadership Team

(SALT).

Each SALT member has a role paralleled with the school senior

leadership team,

and each senior leader works with their student counterpart, partly as

coach

and mentor and partly on common agendas. Like the adult leadership

team, SALT

has both team and individual plans that members shape, and they follow

staff

performance management practice. CH described the thinking behind

making this

change:

We

show them how we do our jobs and how we lead. So the student

principal and I

meet and talk about how you create a cohesive team from a disparate

group of

people, how you get people to buy into it, how, when things

aren’t going as you

planned, or when things are in crisis, you get people back to thinking

about

core values.

The

first SALT group went through an application and interview process,

against job

descriptions, which was carried out by a local business organisation. A

further

feature was investment in leadership training for appointed students,

buying in

professional, adult-derived programmes. This intense focus on building

leadership capability included explicitly the scope to challenge the

school

leadership using evidence and argument. Again, student numbers involved

initially are relatively small, about 5% of the student body.

Interviews for

the second cohort were due to take place soon after the second research

visit.

The number and nature of roles was being expanded, and the numbers

interested

in applying had grown dramatically from the first year.

In

all three cases, each head needed, along with their own commitment, the

involvement of other staff to take this initiative forward. In all

three cases,

this was someone selected or identified by the head, not always an

established

teacher but someone they saw as a key agent for wider change.

A

recurrent theme in interviewing those staff leading this work, whether

their

background was in teaching or not, was their assessment of the

distinctive

skills required of adults, themselves included, to help students

develop in

this way. They perceived these as quite different from those

normally required

of a classroom teacher, and spoke of the tensions their work sometimes

caused

with their colleagues.

The

nature of this difference is linked to the role of facilitator,

identifying

when and how to give up control, but on a constantly shifting basis. It

was

best summarised by the coordinator at Ashtree. She described her

role in relation to the senate as one of facilitation, before adding

that she

was still learning the art.

I

tend to veer on telling them what to do too much, not getting that

balance of

being able to say “OK, right now, for this two minutes,

they’re ready to run

with it” and then maybe two minutes later having to be quite

directive. So

it’s having those skills to sit on your hands, stop telling them

what to do,

but also making sure they’re successful and the projects work,

because if you

just let them fail, then they won’t try again.

A

young teacher early in her career had recently taken over

responsibility at

Birchgrove. She shares a similar vision of facilitation to the one

described at

Ashtree and was clearly aware of the sensitivities and tensions in her

role.

When

I took over I was very much of the opinion that I wanted it to be run

by students.

I felt it was important because it’s the students’ voice,

and teachers

interpret what students say perhaps not as a student means it. If

it’s done in

student-speak, by students, I felt that was important.

The

skills and insights inherent in these two views appear crucial to

successfully

navigating the tensions identified in the literature review.

2.

What

effects does the development of student leadership have?

There

are two potential areas of effect for student leadership; the effect of

student

leaders on others, both within and beyond the school, and the effect of

the

experience on student leaders themselves. It was only possible within

the scope

of this research to consider both of these from the viewpoint of the

students

involved, cross-checking these with the views put forward by school

leaders.

The research design could not allow the possibility of seeking out what

Fielding and Rudduck (2002) called the ‘silent voices’,

those who, by

choice or not, were not part of that circle. However the survey

evidence from

students, as well as the focus group evidence from staff, gave grounds

to think

there were those in both groups with reservations or resentment:

They

get to see more of the head than we do (Staff

member, Birchgrove)

Only

the student leaders find out what’s going on in the school (Student,

Ashtree).

Notwithstanding

those limitations, and whilst it was not possible to test out the

objectivity

of their views, it does seem significant, firstly, that every student

leader

interviewed was able to point to some personal development as a result

of their

experience. It could be possible the sample made available by the

schools,

within the constraints of availability, timetables and examinations,

was biased

towards more enthusiastic students. Nevertheless, in each case a

significant

proportion of potential interviewees was seen, 25% at Ashtree and

around 60% at

Chestnut, although the proportion, not the number, at Birchgrove was

smaller

(about 12% in all). It is also clear a number of those interviewed, in

all

three schools, were not simply traditionally well-behaved, conforming

students.

It

is beyond the scope of this research to attempt any linkage, causal or

otherwise, between involvement in student leadership and academic

success,

either for individuals or schools. But each head defined their purposes

in

developing their stakeholder engagement strategy, and student

leadership within

that, in terms that begin with their students and the educational

outcomes for

them. However, they also defined these outcomes in much broader terms

than

current measures of purely academic attainment. The various terms in

which they

expressed this, again showing both commonality and distinctive

emphases, are

shown in Table 3. All are connected by ideas of self-esteem and

of building

relationships with adults.

|

AH

|

BH

|

CH

|

|

Understanding

of adult world

Development

of social

and emotional intelligence

|

Employability

Enterprise

|

Confidence

Opportunity

for role and

responsibility

|

Table

3: Language used by heads to describe desired outcomes

There

is a strong echo between some of these aims and the language used by

students

to express their view of what they felt had been the impact for them. Their

views are summarised below.

Key words include confidence, relationships, tolerance, and team work,

or, in

other words, relationships and self-esteem again. They all point to

changes in

their schools they believe they have effected. At Ashtree in particular

the

effect is also beginning to extend beyond the school into

students’ own wider

communities.

|

|

Ashtree

|

Birchgrove

|

Chestnut

|

|

Student-identified effects on school/others 2011-12

|

- Changing peoples’ opinion of school for better

- Giving community more insight into school

- Organisation of student survey

- Community befriending scheme

- Organised community Fun Day on school site

|

- Changes to uniform

- Changes to school organization

- Help to appoint new Vice-Principal

|

- Improved relationships and trust within academy

- Planning a vending machine and shop

- Application for laptop funding

|

|

Student-identified benefits for self

|

- Confidence

- Improved behavior

- Ability to make relationships

- Speaking in public

|

- Speaking to groups

- Decision-making

- Political awareness

- Determination

|

- Confidence

- Dealing with stress

- Tolerance, and understanding of people, including teachers

- Working as a team

|

Table

4: Benefits identified by student leaders

Interview

examples:

What

annoyed me was a lot of the people who go on about this school is

rubbish have

never actually been here so they don’t know what it’s

like. I wanted to make

some changes and work with the community so people can see that, yes,

this

school does have problems, but it‘s not as bad as people think. I

think it’s

working. We’ve got much higher opinions of us. Students are took

into account

about the community. Down the Hill last year, everyone used to

throw apples to

cause trouble, but now we‘ve been there and spread the word to

students, it’s

not been as bad, and our Police Community Support Officer has come and

helped

us on that.(Y9 Student, Ashtree)

I’m

not

afraid to say that I wasn’t the easiest person to have in a

classroom when I

was younger. But through (the leadership work I’ve done)

it’s given me a second

chance and let people look at me twice and realise I’m not that

person. I’ve

really changed a lot since I joined this school and I think

that’s down to

them, the way my character has been built up. The fact I can go

from being

trouble to being Student Principal shows the encouragement I’ve

had has helped

me to progress and hopefully develop who I am. (Y12 Student, Birchgrove)

All the

kids muck around in school because they don’t like some staff,

like Miss T.

But through SALT … I had a meeting with Miss T once

when I was doing the

charity events, and we didn’t just have a basic conversation on

that, we ended

up talking lady to girl. It was work to work, basically a friend to

friend.

Then after you’ve had conversations based on work, and then moved

into

something else other than work, you know that Miss T and some other

teachers

aren’t actually that bad, and you develop a good relationship

with them and you

feel like it’s out of order when everyone starts saying stuff.

(Y10 Student,

Chestnut)

Thomson

(2012) reports similar findings about learning outcomes from student

leaders in

another context, but notes how little work has been undertaken to

assess the

learning gains from student voice and leadership and to involve

students in

this process. That would be true in these schools too. Addressing this

gap may

be central now to finding a new balance between the functional and the

personal, to use Fielding’s terms.

Where

the students expressed with the greatest force and passion the impact

they felt

they had made and had experienced in themselves, at Chestnut, it may be

significant this school had invested significantly in leadership

development

training for those students, using adult-derived models and off-site

locations.

The model of shadowing and being mentored by senior leaders in the

school also

kept a real focus on leadership rather than passivity or

compliance. When CH

was asked what would happen, in practice, if students disagreed with a

direction being taken by their mentor, she replied:

I

quite like a bit of disagreement. If you’re disagreeing about

values or vision

then there’s something really healthy in that discussion. If

there’s

fundamental disagreement, you get them to go away and undertake a piece

of

research —‘okay, if you think you’re right, come back

and show me, give me the

evidence’. That’s what I’d do with an adult

leader, if one of my leadership

team disagrees with me. I think the same should apply to students.

This

attitude and understanding may represent a key differentiator in the

development of a ‘person-centred’ organisation as

opposed to a merely ‘high-performing’

one (Fielding 2006). It was also starting to affect the understanding

of other

school leaders. For instance, a new assistant headteacher, speaking

eight weeks

after her arrival from a leadership post in another school designated

by OFSTED

as outstanding, said:

In

other schools I’ve had student leadership in the sense of giving

them

responsibility, but I realise now (after being here) it was mostly

operational

not strategic. The guidance we were giving was on an operations basis,

not

about them thinking modelling, challenging, doing … actually

being leaders. So

I wonder whether some schools think they’re doing it, whereas in

reality

they’re just directing, task-orientated.

Robinson and Taylor (2013), based on a study of two

student voice projects in schools, question whether it is at all

possible that “staff

and students can meet as genuine partners with a shared undertaking of

making

meaning of their work together” (p.44). However, the

potential for

transformation in the three case studies does not come from school

leaders

simply listening to suggestions from students for changes they think

might be

beneficial, nor in simply coopting some students to act as proxies for

school

leaders. Rather it seems to lie in the relationships with teachers and

other

adults that develop as a result of sharing concerns, and the way in

which

mutual respect and understanding increases through shared

responsibility. This

is well illustrated by the Chestnut student cited in Table 3 discussing

her

changed attitude to Miss T. Her comments do not suggest ‘synthetic

trust’

(Czerniawski 2012). They have resonance with the findings of Mitra

(2009)

relating to the significance of youth-adult relationships and of Moloi

et al

(2010) regarding mutual trust between students and teachers as a key

driver of

improvement. They are perhaps offering a glimpse of the essence and

beginning

of transformation.

Conclusion

The

research evidence gathered so far suggests the possibility of a

significant

reciprocal relationship between the development of student leadership,

with its

dual characteristics of agency for change and community engagement, as

opposed

to simpler understandings of student voice, and the wider growth of

trust and

engagement in a school, which may in turn be linked with potential for

transformation.

It

remains true that, while all three schools involved students from a

wide age

range, not just the oldest, and from a range of backgrounds, the number

of

students involved as leaders in each school is relatively small.

One of the

challenges confronting each head is, if there are real personal

development

benefits for individuals and for the school, how they extend these to a

much

greater number of students, and ultimately to all.

All student leaders reported that they developed a

range of skills including confidence, presentation, working with

people, and

understanding of decision-making and group processes, but there is as

yet no

mechanism for capturing and recognising this learning. The strongest

impact

appears to occur where there are clear roles and a strong focus on

leadership

development and coaching for students involved, and this investment may

be a

critical factor for success.

But the most critical success factor is perhaps the

recognition that fostering of genuine student leadership, as opposed to

simply

on ‘an operations basis’, requires distinctive

support, skills and

judgment from adults, which are not the same as those normally

associated with

classroom teaching. Understanding these skills and developing them,

whilst

addressing the tensions that will flow if other staff do not also

understand

them, at the same time acknowledging with insightful sensitivity the

inescapable presence of a power dimension, may be the next key

challenges for

this work.

Clearly

this is, at this stage of the research, a partial and preliminary view.

It

opens up lines for further enquiry and more extensive study over time

to

develop fuller understanding of the processes at work, of the real

possibility

and impact of student leadership in terms of transformation, and of its

wider

implications both for school leadership and for teaching and learning.

Acknowledgements

I

am indebted to the heads, staff and students of the three schools for

their willing

and open engagement in the research, and to my supervisor, Dr Justine

Mercer,

for her continuing constructive critique and encouragement in seeking

meaning

within the data.

List

of tables

Table

1: Analysis of understandings of student voice – Thomson and

Gunter (2006)

Table

2: Schools’

approaches

to student leadership

Table

3: Language used by heads to describe desired outcomes

Table

4: Benefits

identified by student leaders

References

Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B.

(2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. New

York:

Russell Sage Foundation.

Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, presence, and

power: ‘Student voice’ in educational research and reform.

Curriculum

Inquiry, 36(4), 359–390.

Czerniawski,

G. (2012). Repositioning trust:

a challenge to inauthentic neoliberal uses of pupil voice. Management

in Education, 26(3), 130-139.

Day, C., Sammons, P., Hopkins, D., Harris, A.,

Leithwood, K., Gu, Q., Brown, E., Ahtaridou, E. and Kington, A. (2009).

The

Impact of School Leadership on Pupil Outcomes; DCSF Research Report

RR108;

University of Nottingham.

DfE (2010). The

Importance of Teaching Schools White Paper:

http://www.education.gov.uk/schools/toolsandinitiatives/schoolswhitepaper/b0068570/the-importance-of-teaching

Fernández, W. D. (2004). The Grounded Theory

Method and Case Study Data in IS Research: Issues and Design.

Information Systems Foundations Workshop: Constructing and Criticising,

Vol. 1:

43-59. School of Business and Information Management, Faculty of

Economics and

Commerce, Australian National University: Canberra, Australia.

Fielding,

M. (2006). Leadership, radical

student engagement and the necessity of person‐centred

education. International

Journal of Leadership in Education, 9(4),

299-313.

Fielding,

M., & Rudduck, J. (2002). The

transformative potential of student voice: confronting the power issues.

In Annual Conference of the British Educational Research

Association,

University of Exeter, England (pp. 12-14).

Goddard, R. D. (2003). Relational

Networks, Social Trust, and Norms: A Social Capital Perspective on

Students'

Chances of Academic Success. Educational Evaluation and Policy

Analysis,

25, 59-74.

Hallinger,

P. (2011). Leadership for

learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. Journal

of

Educational Administration, 49(2), 125-142.

Hallinger,

P., & Heck, R. (2003).

Understanding the contribution of leadership to school improvement. In

Wallace, M. & Poulson, L. Learning to read critically in

educational

leadership and management. Sage: 215-235.

Harper, R. and Kelly, M. (2003). Measuring

Social Capital in the United Kingdom. London, Office for National

Statistics.

Lavery,

S. D., & Hine, G. S. (2012). Principals:

Catalysts for Promoting Student Leadership. Principal Matters.

Leithwood,

K., & Riehl, C. (2005). What do

we already know about educational leadership. A new agenda for

research

in educational leadership, 12-27.

Lilley,

R. (2010); Problematising

student leadership. Doctoral dissertation, Unitec Institute of

Technology.

McGregor,

J. (2007). Recognizing student

leadership: schools and networks as sites of opportunity. Improving

Schools, 10(1), 86-101.

Mertkan-Ozunlu,

S. and Mullan, J. (2007);

'Students as Agents of Educational

Leadership: Case Study of a Specialist Media Arts School', paper

presented

in ECER, Ghent.

Mitra, D.L. (2009); Collaborating with

Students:

Building Youth‐Adult

Partnerships in Schools. American Journal of

Education, Vol. 115, No. 3 (May 2009), 407-436.

Moloi, K.C., Dzvimbo, K.P., Potgieter, F.J.,

Wolhuter, C.C. and van der Walt, J.L. (2010); Learners’

perceptions as to

what contributes to their school success: a case study. South

African

Journal of Education Vol. 30:475-490.

Ransom, S. (2000): Recognising the pedagogy of

voice in a learning community, Educational Management and

Administration,

28(3), 263–279.

Robinson,

C., & Taylor, C. (2013). Student

voice as a contested practice: Power and participation in two student

voice

projects. Improving Schools,16(1), 32-46.

Rudduck, J., Chaplain, R. & Wallace, G. (1996). School

improvement: what can pupils tell us? London, David Fulton.

Rudduck J. & Fielding, M. (2006): Student

voice and the perils of popularity. Educational Review, 58:2,

219-231.

Thomson,

P. (2012). Understanding,

evaluating and assessing what students learn from leadership

activities:

student research in Woodlea Primary. Management in

Education, 26(3),

96-103.

Thomson,

P. and Gunter, H. (2006); From ‘consulting pupils’ to ‘pupils as

researchers’: a situated case narrative.

British Educational Research Journal Vol.

32, No 6, 839–856.