Sam

Hind, University of

Warwick and Alex Gekker, Utrecht University

Abstract:

The

automotive world is evolving. Ten years ago Nigel Thrift (2004: 41)

made the

claim that the experience of driving was slipping into our

'technological

unconscious'. Only recently the New York Times suggested that with the

rise of

automated driving, standalone navigation tools as we know them would

cease to

exist, instead being 'fully absorbed into the machine' (Fisher, 2013).

But in

order to bridge the gap between past and future driving worlds, another

technological evolution is emerging. This short, critical piece charts

the rise

of what has been called 'social navigation' in the industry; the

development of

digital mapping platforms designed to foster automotive sociality. It

makes two

provisional points. Firstly, that 'ludic' conceptualisations can shed

light on

the ongoing reconfiguration of drivers, vehicles, roads and

technological aids

such as touch-screen satellite navigation platforms. And secondly, that

as a

result of this, there is a coming-into-being of a new kind of driving

politics;

a 'casual politicking' centred on an engagement with digital

interfaces. We

explicate both by turning our attention towards Waze; a social

navigation

application that encourages users to interact with various driving

dynamics.

Keywords:

Social

navigation, ludic

interaction, GPS, casual politicking, digital mapping technologies,

automobiles

Introduction

City

streets are now a mesh of software and materiality. New technologies

are

changing the way drivers interact with their own vehicles, the wider

driving

environment, and other road-users. Satellite navigation devices -

perhaps the

ultimate driving aids - are adept at capturing, storing, tracking,

anticipating

and visualising the vast array of possible driving interactions, much

more so

than the traditional A-to-Z road atlas. But just like the humble

latter, the

former is called upon to adjudicate in everyday navigational matters.

In this article

we will look at how 'social navigation' - a term coined by the

developers of a

satellite navigation platform called Waze - is arguably changing the

everyday

nature of driving. This work aims to build on an expansive literature

that has

interrogated the evolving socio-technical nature of automobility (Dodge

and Kitchin, 2007; Featherstone, 2004; Sheller, 2007),

and continues with an

interdisciplinary sensibility befitting a world in which engineers,

technologists, advertisers, executives and lay people combine with

pistons,

onboard electronics, and social media campaigns to not only eradicate

the clean

distinctions between the production and consumption of such driving

experiences,

but also to prove further the emerging 'assemblage' of everyday

mobility (Dant,

2004). Here, then, we intend to make two provisional, exploratory

points.

Firstly,

we contend that 'ludic' approaches to analysing digital technological

networks,

such as the driver-car assemblage, can help to close any lacunae in

thinking on

the possible reasons behind the insatiable take-up of new satellite

navigation

technologies by publics around the world. By ludic approaches, we mean

any

analyses that take 'play' to be an inherent component in social

relations. As

the videogame world loses its already precarious exclusivity over the

concept,

new driving technologies premised on touch-screen interaction are

drawing on

playful mechanics in order to stimulate habitual engagement. These

range from

point-based scoring systems and game-like avatars to wholly

manipulable, editable

and mutable platforms in common with the 'sandbox' worlds of Grand

Theft Auto

(Chesher, 2010).

We

then

employ the notion of ‘casual politicking’ (Gekker,

2012)

to orientate

new understandings of the ways in which drivers engage with digital

interfaces.

This term, we believe, appropriately encapsulates the kinds of moves

being made

in the automotive industry even ten years ago, when Nigel Thrift (2004:

41)

made the claim that the experience of driving was slipping into our

'technological unconscious'. The naturalisation of the mechanics of

everyday

driving has created the conditions for a subconscious, 'casual' form of

politics; one formed through an interaction with digital devices. We

exemplify

this with reference to the social navigation application mentioned

above - Waze

- taking particular interest in three dynamics: the reporting of road

hazards,

the collaborative management of vehicle flow, and the addressing of

latent map

errors.

Ludic

Interaction: From Gamification to the Casual

The

‘ludic

turn’ in new media studies has argued that play is a fundamental

component of

all human culture, even turning up in the very domains often

'considered the

opposite of play' (Raessens, 2010: 6) like education, politics,

business and

modern warfare. It is suggested that a ludic outlook pervades all

manner of

everyday practices and all kinds of interactions with digital devices,

rather

than being restricted to a specific game space, or 'magic circle'

(Huizinga,

1955; Salen and Zimmerman, 2004). As Glas (2013: 4) suggests, this

'formalist'

separation between the play world and the 'real' world belies the

pervasive

nature of ludic activity throughout the whole of human life.

Interaction with

any kind of interface - be it a desktop computer in the workplace, a

cash

machine in a shopping centre, a mobile phone on public transport, or a

games

console in the home - permits ludic behaviour. In many cases, as will

be

discussed, it is positively encouraged. Advancing an understanding of

how

digital interfaces are being played

with, and especially, as being played casually and daily (rather than in any 'magic' game space) has

therefore become a primary concern. Interfaces are not

simplistic

windows into an isolated realm (cf.

Manovich, 2001)

but instead are enablers of general, social practices (Galloway,

2012).

As such there is a politics to their design, functionality and

deployment.

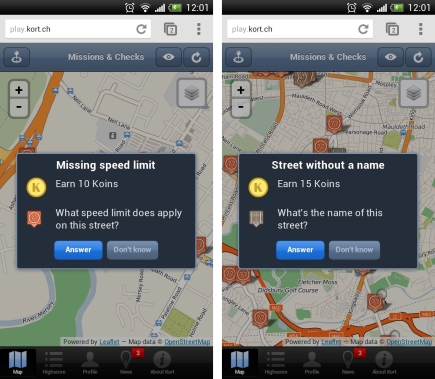

Within

the ludic turn more specific changes have

been noted. One is ‘gamification’ (Bogost,

2011; Deterding et al., 2011; Mosca,

2012).

The

adoption of game-like mechanics, rules, modes and structures for

everyday tasks

is now widespread, although only recently taken up in the field of

digital

mapping, for example. Those who contribute to collaborative mapping

platforms

such as OpenStreetMap (OSM) can use an application called Kort to carry

out missions

collecting ‘koins’ and badges to rise up a leaderboard,

which in turn, improves

the validity of the OSM database. Humanitarian volunteers looking to

contribute

in the aftermath of natural disasters can also now do so digitally via

a

platform called MicroMappers. Each case is a step-change from how the

process

of digital map editing has historically been performed.

But

in

the context of automotive practice, the possibility of 'cognitive

distraction'

(AAA, 2013) from mobile application interaction whilst driving has

provided a

level of concern not present in other debates (Roose, 2013; Richtel and

Vlasic,

2013), even if recent legal ruling has deemed their use whilst driving

acceptable under certain conditions1.

Design prototypes such

as

Matthaeus Krenn's 'New Car UI' (2014)2

suggest that new

modes of

interaction are necessary to combat this perceived distraction whilst

driving. 'Social

navigation', then, is perhaps a tentative evolution stretching the

limits of

current statutory frameworks, cultural norms and acceptable levels of

bodily

attention.

A

second, complimentary shift that the ludic turn has cast attention

towards is

the growing casualness of game-playing itself (Juul,

2009).

Distinguishing

casual games from ‘hardcore’ games as Abt (1987) and

Ritterfeld et al. (2009) have, allowed for a

deeper understanding of how ‘gaming capital’ is built-up (Consalvo,

2007)

and

play conventions are acquired (Pargman

and Jakobsson, 2008).

Typically casual games are defined by

low barriers to entry (easy to pick-up), incremental progress (lots of

short

levels), forgiveness towards player mistakes and the use of

‘social mechanics’,

such as the option to invite or compare results with friends on social

networking sites (Juul,

2009).

Additionally, they

often include 'micro-payments' to unlock bonus content as opposed to

traditional

‘pay-once for everything' models.

The

growth of mobile platforms - smartphones and tablets - has contributed

greatly

to their uptake. Playing the best-selling Angry Birds game for 2 hours

a month,

as creator Peter Vesterbacka suggests many do, would only amount to

around 4

minutes of play a day (Braw, 2013). A significantly lower figure than

just

about any traditional console game, and one that suggests many simply

play such

games to 'kill time' in between other tasks, as Bouca (2012: 7) finds.

As such,

these casual gamers portray a relatively different set of attributes

and

interests to other long-form players. The titles they play stand at the

far end

of a long gaming continuum, with the vast, immersive (and

'hardcore’) worlds of

Halo and Bioshock at the other end.

Just

as digital maps have allowed us to capture, track and store the records

of

quotidian interactions and expressions, so games have become embedded

within,

and arguably transformed everyday life, constituting a gamification of

common

rituals (Kort as map editing game)

and a casualness of the game-playing itself (Kort as a

smartphone optimised

editing platform). The fact that many games make use of maps as their

playing

boards, whether imagined (Total War, Civilization) or through the

utilisation

of location-based data (Ingress, Zombies, Run!) (Lammes 2011), only

underscores

how digital mapping and gaming share common interface characteristics.

The

Grand Theft Auto (GTA) series is perhaps the most obvious example of

this

commonality. As Chesher (2013: 316) suggests, both satellite navigation

interfaces and contemporary video games are primed to do three similar

things;

reify route-making, subjectively orientate action, and normalise the

overlay of

'real-time' data. Gameplay in open world titles such as GTA is

non-linear,

allowing players to roam freely and complete tasks at will.

The

adoption of touch-screen interfaces embodies a drastic turn in the

nature of

digital game-playing, map editing and technological driving assistance.

The

intuitive and ludic nature of capacitive sensing technologies (Verhoeff,

2009)

as

well as the possibility of tentative, probing and proximal interaction

with such

mobile devices (Paterson,

2007)

have led to their now-almost ubiquitous presence. In allowing for

quicker and,

arguably, more intuitive control in everyday situations (driving

included) such

interfaces utilise playful bodily action as a mechanism for increased

coherence

in habitual practices such as scrolling menus, issuing commands and

selecting

phenomena. A plethora of new tactile strokes, sweeps and taps are

steadily and

qualitatively replacing the metronymic and calculative clicks of

computer mice,

keys and other vehicular dashboard controls.

The

touch-screen

interface is a ‘thin, but essential and visible membrane’ (Verhoeff,

2012)

at once inviting seemingly

inconsequential moves whilst actualising wider cognitive, cultural and

'micro-political'

potentialities. Both gamification and casualisation are dependent upon

this

precept. The new driving landscapes that arise from such interaction

are similarly

transparent and innocuous, but nonetheless shape and direct the actions

of everyday

drivers. To illustrate, next we will examine the social navigation

application

Waze.

Hazards,

Flows and Issues: Outsmarting Traffic Through Collaboration

Unlike

standard GPS software, Waze populates the driving interface around a

constellation of fellow drivers. As a smartphone application it

competes with

the standalone device market (TomTom, Garmin etc.) and other free

turn-by-turn

applications such as Navfree. In 2012, Waze had a global community of

36

million drivers, sharing a total of 90 million traffic reports, and

driving a

collective 6 billion miles. 65,000 map editors also made 500 million

map edits,

reflecting 1.7 million on-the-ground changes (Waze,

2013a).

OSM by comparison, had just fewer than

100,000 editors in 2012 making 800 million edits (OpenStreetMap,

2013).

But

as alluded to in the introduction, it is not necessarily easy to make a

clean

split between those who 'produce' the map, those who 'edit' the map and

those

who 'consume' the map. It is easier, rather, to conceive of a kind of

data feedback

loop, where Waze users contribute - knowingly and unknowingly - through

active driving,

desktop editing and passive metadata collection. These feed back into

future

route-calculation. The data gleaned helps to not only build up a vast

picture

of the journeys made with Waze, but also the state of the road network

in

general.

The

application's mechanics thus have a circulatory function, as user

action builds

a more comprehensive database. But as the database updates so does the

digital

map. The status of roads, the designation of speed limits, the set-up

of

junctions and vehicle restrictions are all changeable based on user

data. Due

to this active enrolment the digital map itself does not serve as a

mere

representation of the road ahead: it transforms the very driving world

itself. It

becomes a ‘mutable mobile’ (Kitchin

and Dodge, 2007; Lammes, 2008)

- an object capable

of changing shape and moving across territory - rather than being an immutable mobile (Latour, 1986) as maps

have traditionally been conceived as. Other satellite navigation

systems

present the driving world as an immutable 'base map' upon which to

plant the

individual driver. But this world is bare and lifeless; phenomena are

rendered

foundational but unerringly quiet and impervious to change. The driver

simply

glides over the surface with no knowledge of what is

“below”, let alone with

the possibility of altering it. In the Waze world the digital map

exists on the

same ontological plane as the road environment itself - as a fluid,

transportable object.

Road

hazards, vehicle flow and map issues, for example – three

dimensions of the

Waze driving experience – all exist on this same active platform;

open and malleable

to the driver. They are dynamics that feed into this data loop between

driver,

database and map. Thus, this form of satellite-aided navigation is a

performative act that does not relegate the map to a secondary level

beneath

the ‘real driving world’ of asphalt, traffic lights and

junctions. Ludic mechanics are central to

how our primary

example encourages this performance with the mobile interface and

reconfigures

the act of driving. This reorganization, we argue, has a distinct

political

dimension as drivers are gifted the ability to fundamentally change the

driving

landscape as they travel through it, challenging the way in which we

have

historically relied on state agencies to provide us with information on

road

conditions.

Reporting

Hazards

One

of

the main features of Waze is the ability to identify hazards. Spotting

potential dangers for other users (or 'Wazers') is not just a handy

addition to

an otherwise social tool however, but a potentially valuable driving

aid. These

notifications ameliorate the disruption caused by three types of

hazard: obstructions,

distractions and anticipatory impediments. Obstructions provide direct

dangers

(debris, barriers), distractions are indirect and usually visual

disturbances

with the potential to become driving dangers (live animals, bad

weather),

whilst anticipatory impediments affect the ability of the driver to

make

upcoming judgments (stationary vehicles, missing road signs). Although

these driving

hazards are the product of loose interpretations, with their existence

precarious, users are nevertheless instructed to pin the incident down.

Once

submitted the hazard is placed on the map as a geo-located

‘pop-up’ message.

This codification is vital for collective map use. It renders a

(relatively)

solid, isolated and verified incident upon which to act. As

encouragement, Waze

users receive a number of points for their contribution of a hazard,

and similar

to consumer reward schemes and videogame 'combo' moves, additional

bonuses are

available for greater contributions such as detailed descriptions,

photo

evidence and weekend notifications.

Altering

Flow

In

addition users can also collectively affect vehicle movement, direction

and

flow by closing existing roads, verifying nascent routes and opening up

entirely

new ones. Although traditional satellite navigation systems are capable

of

keeping users up-to-date with road information that adds to an already

existing

map (TomTom’s Live Traffic etc.), Waze is unique in its

crowdsourcing of wholesale

map recalibrations. As mentioned earlier, users have to be live drivers

to make

changes, although passive (meta)data collection does, as mentioned

earlier,

take place (Couts, 2013). Navigational assistance for other drivers is

therefore grounded in the performative act of driving (or

‘Wazing’ as it is

known), and alterations cannot be made either by desktop or without GPS

and a data

signal3.

This

interaction between the existing (imperfect) map as noticed through the

Waze

interface and the unaligned driving world as seen through the vehicle

windscreen provides the catalyst for contribution. Road closures can be

attributed to an on-road hazard (car crash, fallen tree), a

construction job

(road re-surfacing, underground repairs) or a local event (marathon,

street

party, protest march). Users make the selection by tapping the

appropriate

direction of the closure on the Waze driving map, and ‘no

entry’ symbols notify

others of the diversion. Unlike the previous hazard category, flow

incidents

are shown as linear overlays rather than isolated symbols. This allows

active

drivers to take heed of automatically re-calculated paths once the map

is

updated to reflect the changes. Wazers can also ‘thank’ the

initial user

reporting the issue in much the same way Facebook users can 'like' a

post and

Twitter users can 'favorite' messages. These tactile interactions on

the

smartphone screen render playful, casual interaction with the platform

as

default.

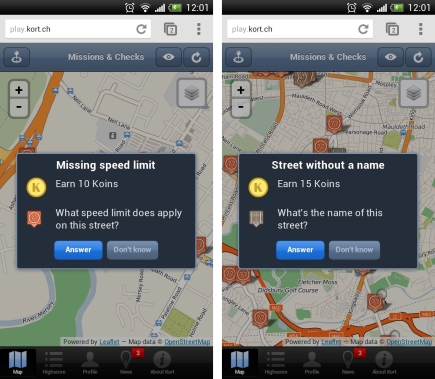

Routes

that have been imported into the Waze database or created in the Waze

Map

Editor can also be verified by drivers in a process called 'road

munching'. In

an unverified state these roads show up as sequential dots as opposed

to a single,

continuous line, but as drivers trace the route they ‘munch'

these dots akin to

Pacman characters, successfully turning them into completed, verified

and

drivable routes for other users (Waze,

2013c).

Similarly,

Wazers can bring new driving worlds into being directly

through the 'road recording' function. By comparison, OSM

editors are required to use applications such as OSMTracker or a

traditional

GPS receiver to record new tracks, and edits still have to be uploaded

through

JOSM, Potlach or another OSM editor. Drivers using traditional

satellite

navigation devices do not possess this 'real-time' editorial

capability, but Waze

users are able to map new roads live and on the move4.

Wazing,

road munching and road recording are actions populating, verifying and

building

a live navigational environment through collaborative driving

performance. On

this evidence Waze is more than simply an addition or ‘aid’

to the driving

experience: it is a direct agent in the act of driving itself. The

ability to

open, close and verify roads on a map interface has heretofore existed

as a

preserve of either state agencies or satellite navigation companies.

This shift

in agency is therefore a significant one. Whilst many other aspects of

society

have been transformed by open, collaborative and citizen-led agendas,

the

driving world is relatively late to the party. Waze represents the most

advanced example of this shift to date.

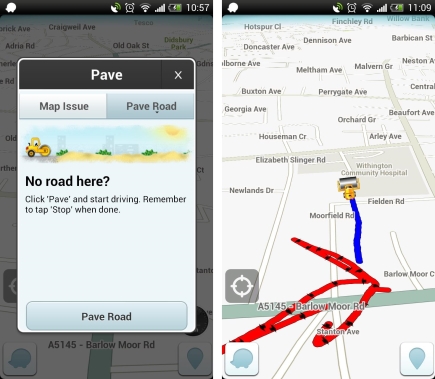

Flagging

Issues

As

a

final dynamic, users can also flag navigational issues. The Waze

application

allows users to report map errors whilst driving, with reports linked

directly

to the location of the error via GPS. These performative edits are

based on the

habitual know-how of drivers. If users believe the Waze map has a

problem they

are permitted to raise a concern. Common issues ranging from forbidden

turns

and incorrect junctions to missing bridges, overpasses or exits are

pre-listed,

but users are also given space in order to detail a more specific, or

irregular

error. But unlike the ‘external’ hazards discussed

previously, the 'internal' map

issues function progressively updates the application itself.

Rather

than dedicating time and energy to large swathes of track uploads as is

routine

in many collaborative mapping projects, users can clean up map errors

as they drive.

Although missing roads can be live-mapped by Wazers desiring to travel

the

unpaved route, the map issue function allows drivers to flag up

potential

errors for others to investigate. Rewards range depending on

prolificacy, offering

users a reason to alert others to errors they might otherwise ignore.

As a

specific example, Waze offers up candy treats for drivers willing to

verify map

data; planting bonuses in cul-de-sacs and other side-roads to tempt

them, with the

points contributing to the same general scoreboard as hazard reports,

distance

milestones and road munches. Once again, the users' avatars gobble

these 'goodies'

up in a Pacman-fashion, with varying totals based on the scarcity of

particular

treats.

Casting

a critical lens on this practice, it could be suggested that such

‘gameful

design’ (Deterding

et al., 2011),

rather than

providing a kind of playful, emancipatory service, in fact simply masks

a volunteered,

mass data-collection practice for a major digital technology enterprise

(now a

division of Google Inc.) as 'fun' and somehow socially rewarding.

Participating

in the mapping of road networks users are led to believe they are

contributing

to a common, driving public. Whilst messages received through the

application

imploring users to 'always drive with Waze open' might be characterised

as

helpful tips to aid use in the spirit of this common, driving public,

they also,

arguably, constitute efforts to ensure Wazers contribute full and

extensive

streams of driver data to the Waze/Google servers for exclusive

advertising purposes

(Couts, 2013).

Alerting

other drivers to accidents or hidden police vehicles, for example, are

part of

culturally ingrained driving practices. Such efforts to help

collaboratively

alert others to road accidents, render new routes, or flag map errors

on a

smartphone interface are simply seen as mere extensions of these

historical

actions. But courtesy of the game mechanics deployed in applications

such as

Waze, coupled with their casual use on a smartphone device, error

reporting arguably

becomes an embedded and naturalised interaction - a 'technological

unconscious'

(Thrift, 2004) - rather than a forced action associated with

traditional forms

of labour. This hybrid practice being what Julian

Kücklich (2005) has famously termed 'playbour'. As a new

field of

politicised action, this ludic interactivity permits a wholly different

- and

perhaps pernicious - force.

Each

of the above exemplifies a new kind of automobile tactic; a new way of

attending to the disturbances, disruptions and hazards in the driving

world.

Historically drivers have been unable to have any effect on the

collection,

verification and visualization of road data, aside from passive

participation

in the network itself. But as applications such as Waze have embedded

themselves into everyday spatial routines, collectively involving users

in the

creation of such publics, there have been radical alterations to the

contemporary

driving experience.

Mapping

Futures

In

this paper we have suggested a rise of so-called social navigation. But

as

future driving worlds increasingly look fully-automated - with

driverless

vehicles, mechanical parking systems and all manner of sensor-mediated

technologies - will this become somewhat oxymoronic? Or, as perhaps we

argue,

will the present technological preference for social platforms become

further

integrated into future driving experiences? Our two-fold analysis has

enabled

us to tease out the nascent dynamics. In the first instance, we have

argued

that ludic interaction is increasingly - thanks to the simultaneous

rise of

both touch-screen devices and social platforms - the default mode for

automotive navigation. The multi-touch gestures routinely demanded by

satellite

navigation systems are replacing the metronomic clicks of plastic

console buttons,

or the circular motion of radio volume and airflow dials. As a way of

engaging

individuals, social navigation applications such as Waze incorporate

many of

the ludic features more commonly witnessed in the gaming world.

In

the second, we have then contended that this ludic interactivity is

breeding a

new kind of political action; one premised on the everyday practice of

driving-with-devices. Although we do not necessarily suggest that other

political

tropes (vehicle as inscribed status object, carbon emitter etc.) do not

provide

appropriate frameworks for automotive study, we do argue that the rise

of social

navigation is a novel development with the potential to provide rich

empirically-focused work. As has been briefly detailed, Waze engages

its user through

a satellite navigation interface that prompts them to report

hazards, alter flows and flag issues. Each dynamic

affects the act of driving, as well as the constellation of other

drivers. It

brings new driving-worlds and ‘driver-car’ assemblages into

being (Dant,

2004).

Thus

it underlines the act of driving as materially political; as the

practice of

affecting the very geographical possibilities of automobile use through

interactive play with the smartphone device. To understand these

nascent

processes we require a different hybrid view on the nature of driving,

navigation and the social; one that takes into account the casual,

habitual and

the playful.

Acknowledgements:

A

previous version of this work was presented at the International

Cartographic

Conference 2013, in Dresden. The authors wish to thank comments from

the

audience during the 'Playing with Maps' session in particular. Of

course, any

errors contained within are solely our responsibility.

Funding:

This

research has received funding from the European Research Council under

the

European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC

Grant

agreement no. 283464.

Notes:

1 The Californian Court of

Appeal overturned an earlier

conviction of

a man originally found guilty for using his Apple iPhone map

application whilst

driving. See: http://articles.latimes.com/2013/apr/25/local/la-me-abcarian-distracted-driving-20130426

on an initial appeal, and the final Court of Appeal decision here: http://www.courts.ca.gov/opinions/documents/F066927.PDF.

2

See: http://matthaeuskrenn.com/new-car-ui/.

3

Desktop edits can be

made through the Waze Map Editor, but this is

also dependent upon the locations driven in the past 3-4 months (Waze,

2013b).

4

Users are still

prompted to add metadata via a desktop editor.

References:

AAA

(2013), Measuring Cognitive Distraction

in the Automobile, https://www.aaafoundation.org/sites/default/files/MeasuringCognitiveDistractionFS_1.pdf,

accessed 22 January 2014.

Abt,

C.C. (1987), Serious Games, Lanham,

MD: University Press of America.

Bogost,

I. (2011), Persuasive Games:

Exploitationware, http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/6366/persuasive_games_exploitationware.php,

accessed 16 December 2013.

Bouca,

M. (2012), 'Angry Birds, Uncommitted Players', in Local and

Global - Games in Culture and Society, Proceedings of

DiGRA Nordic Conference, 2012, Tampere, pp. 1-13.

Braw,

E. (2012), Angry Birds creator Peter

Vesterbacka, http://www.metro.lu/news/angry-birds-creator-peter-vesterbacka/,

22 January 2014.

Chesher,

C. (2012), 'Navigating sociotechnical spaces: Comparing computer games

and sat

navs as digital spatial media', Convergence,

18 (3), 315-330.

Consalvo,

M. (2007), Cheating: Gaining Advantage in

Videogames, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Couts,

A. (2013), Terms & Conditions: Waze

is a privacy accident waiting to happen, http://www.digitaltrends.com/mobile/terms-conditions-waze-privacy-accident/,

accessed 16 December 2013.

Dant,

T. (2004), 'The Driver-car', Theory,

Culture & Society, 21, (4/5), 61-79.

Deterding,

S., M. Sicart, L. Nacke, K. O'Hara and D. Dixon (2011), 'Gamification:

Using

game-design elements in non-gaming contexts', Human

Factors in Computing Systems conference, Vancouver, BC, 7-12

May 2011.

Dodge,

M. and R. Kitchin (2007), 'The automatic management of drivers and

driving

spaces', Geoforum, 38, 264-275.

Featherstone,

M. (2004), 'Automobilities: An Introduction', Theory,

Culture & Society, 21 (4/5), 1-24.

Fisher,

A. (2013), Google's Road Map to Global

Domination, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/15/magazine/googles-plan-for-global-domination-dont-ask-why-ask-where.html,

accessed 12 December 2013.

Galloway,

A. (2012), The Interface Effect,

Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gekker,

A. (2012), 'Gamocracy: Political Communication in the Age of Play',

unpublished

Masters thesis, Utrecht University.

Glas,

R. (2013), 'Breaking Reality: Exploring Pervasive Cheating in Foursquare', Transactions of the Digital

Games Research Association, 1 (1),

1-14.

Huizinga,

J. (1955), Homo Ludens, Boston:

Beacon Press.

Juul,

J. (2009). A Casual Revolution:

Reinventing Video Games and Their Players, Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Kitchin,

R. and M. Dodge (2007). 'Rethinking maps', Progress

in Human Geography, 31 (3), 331-344.

Kücklich,

J (2005), 'Precarious Playbour: Modders and the Digital Games

Industry', FibreCulture, 5 (25).

Lammes,

S. (2008), 'Spatial Regimes of the Digital Playground: Cultural

Functions of

Spatial Practices in Computer Games', Space

and Culture, 11 (3), 260-272.

Lammes,

S. (2011), 'The map as playground: location-based games as

cartographical

practices', in Think,

Design, Play,

Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference of DIGRA

conference, 2011, Utrecht, pp. 1-10.

Latour,

B. (1986), 'Visualization and Cognition: Drawing Things Together', Knowledge and Society Studies in the

Sociology of Culture Past and Present, 6 (1), 1-40.

Manovich,

L. (2001), The Language of New Media,

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mosca,

I. (2012), '+10! Gamification and deGamification', GAME,

1, http://www.gamejournal.it/plus10_gamification-and-degamification/#.Uq7jSFtdXCs,

accessed 16 December 2013.

OpenStreetMap.

(2013), Editor usage stats, http://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Editor_usage_stats,

accessed 16 December 2013.

Pargman,

D. and P. Jakobsson (2008), 'Do you believe in magic? Computer games in

everyday life', European Journal of

Cultural Studies, 11 (2), 225-244.

Paterson,

M. (2007), The senses of touch: haptics,

affects and technologies, Oxford: Berg.

Raessens,

J. (2010), Homo Ludens 2.0: The Ludic

Turn in Media Theory, Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Richtel,

M and Vlasic, B. (2013), Voice-Activated

Technology Is Called Safety Risk for Drivers, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/13/business/voice-activated-in-car-systems-are-called-risky.html,

22 January 2014.

Ritterfeld,

U., M.J. Cody and P. Vorderer (eds.) (2009), Serious

Games: Mechanisms and Effects, New York: Routledge.

Roose,

K. (2013), Did Google Just Buy a

Dangerous Driving App?, http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2013/06/did-google-just-buy-a-dangerous-driving-app.html,

accessed 22 January 2014.

Salen,

K. and Zimmerman, E. (2004), Rules of

Play: Game Design Fundamentals, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sheller,

M. (2007), 'Bodies, cybercars and the mundane incorporation of

automated

mobilities', Social & Cultural

Geography, 8 (2), 175-197.

Thrift,

N. (2004), 'Driving in the City', Theory,

Culture & Society, 21 (4/5), 41-59.

Verhoeff,

N. (2009), 'Grasping the screen: Towards a conceptualisation of touch,

mobility

and multiplicity, in Boomen, M., Lammes, S. and Lehman, A-S. (eds.), Digital Material: Tracing New Media in

Everyday Life and Technology, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University

Press, pp.

209-222.

Verhoeff,

N. (2012), Mobile Screens: The Visual

Regime of Navigation, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Waze

(2013a), 500 Million Map Edits in 2012,

http://visual.ly/500-million-map-edits-one-year,

accessed 16 December 2013.

Waze

(2013b), Waze Map Editor, http://www.waze.com/wiki/index.php/Waze_Map_Editor,

accessed 16 December 2013.