Emma

Louise Parfitt (University of Warwick)

Abstract:

This

article explores whether traditional oral storytelling can be used

to provide insights into the way in which young people of 12-14 years

identify

and understand the language of emotion and behaviour. Following the

preliminary

analysis, I propose that storytelling may trigger sharing

conversations. My

research attempts to extend the social and historical perspectives of

Jack

Zipes, on fairy tales, into a sociological analysis of young

people’s lives

today. I seek to investigate the extent that the storytelling space

offers

potential benefits as a safe place for young people to share emotions

and

experiences, and learn from one another. My research analysis involved

NVivo

coding of one-hour storytelling and focus group sessions, held over

five weeks.

In total, there were six groups of four children, of mixed ethnicity,

gender,

ability, and socio-economic background, from three schools within

Warwickshire.

The results confirmed that the beneficial effects of the storytelling

space

include a safe area for sharing emotions and experiences, and in

general for

supporting young people outside formal learning settings.

Keywords:

Storytelling, Narrative, Sociology of emotion,

Zipes,

Sharing Conversations

Introduction

[A]ll we

sociologists have are

stories. Some come from other people, some from us. What matters is to

understand how and where the stories are produced, which sort of

stories they

are, and how we can put them to intelligent use in theorizing about

social

life. (Silverman 1998: 111)

In Breaking

the Magic Spell and Fairy

Tales and the Art of Subversion, Jack Zipes discusses what

potential

stories have as a vehicle for influencing behaviour

(1979; 1991; 2006).

Zipes summarises the way in which stories, and the creation of

children’s

literature as a genre, have historically been used to influence

children’s

behaviour. He asserts that stories have the power to socialise young

people in

particular ways. The use of moralistic stories, for instance, asserts

pressure

on young people to conform: ‘to cultivate feelings of shame and

to arouse

anxiety in children when they did not conform to a more inhibiting way

of

social conduct’ (Zipes, 2006: 22). Take for example Aesop’s

fable of ‘The Horse

and the Stag’,

The

Horse had the plain entirely

to himself. A Stag intruded into his domain and shared his pasture. The

Horse,

desiring to revenge himself on the stranger, requested a man, if he

were willing,

to help him in punishing the Stag. The man replied, that if the Horse

would

receive a bit in his mouth, and agree to carry him, he would contrive

very

effectual weapons against the Stag. The Horse consented, and allowed

the man to

mount him. From that hour he found that, instead of obtaining revenge

on the

Stag, he had enslaved himself to the service of man.

The moral here being,

‘He who

seeks to injure others often injures only himself’

(Aesop: 1484).

Zipes argues that such

morals and lessons in children’s literature have the potential to

affect young

people’s behaviour by providing them with examples of appropriate

social

conduct.

As part of my

doctoral research,

I am using traditional oral storytelling to explore whether stories can

provide

sociological insights into young people’s lives. I am

particularly interested

in the extent to which stories socialise young people towards socially

approved

forms of emotional and behavioural expression. The purpose of this

article is

to offer some preliminary results on an ongoing project. The concept of

storytelling as a trigger for sharing conversations was one that

emerged during

transcription of the data. In the context of the focus group

discussions, I

define ‘sharing’ as ‘something personal’ that

incorporates ‘private life,

relationships, and emotions’

(Stevenson, 2010).

I am interested in

the way in

which young people identify and understand the language of emotion and

behaviour

in relation to different narrative influences around them. This is

called

narrative learning: ‘learning from, about and through stories,

and learning

through reflecting on the experience of narrating and the narrating of

experience’ (Cortazzi and Jin, 2007: 645).

I am additionally

interested in

whether young people are aware of the conformative or subversive

effects of

narrative influences around them in the form of literature, TV, films,

video-games, music, media, education, the internet and interaction with

other

people like friends and family. In this article, I will elaborate on

how the

storytelling space I created in my research unexpectedly triggered

dialogues of

sharing between young people aged 12 to 14 years, which I have since

sought to

explore in more detail.

Methodology

For five consecutive

weeks, I

worked with six focus groups in collaboration with three schools in the

Warwickshire area. The groups were, as much as possible, of mixed

gender,

ethnicity, ability, and socio-economic background. I was not able to

access as

full a range of students as I would have liked. For example, I wanted

to

balance gender participation but one of the research sites was an

all-girls

school. I began each focus group with ten to fifteen minutes of

traditional storytelling.

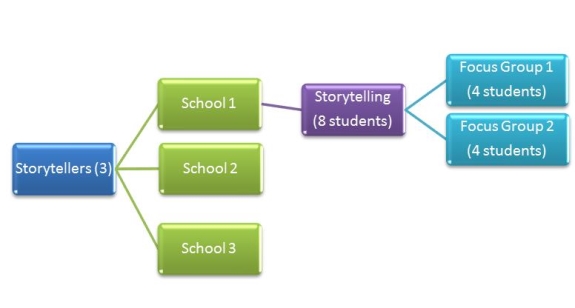

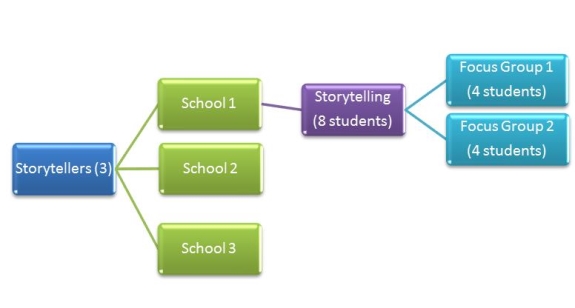

There were eight students in each storytelling group, which I then

divided into

groups of four for the focus group discussion (six focus groups of four

young

people in total, Fig. 1).

My methods and

analysis consider

a range of contextual variables, which potentially shape the outcomes.

These

include the stories themselves, the impact of the storytellers, focus

group

questions, the storytelling space, individual perspectives and

interaction

amongst the students, the role of the researcher, and wider narratives,

which

the students are aware of that interact with the groups’ process

of

meaning-making (for instance, literature, TV, films, video-games,

music, media,

education, and the internet).

Figure 1:

Storytelling Groups

I provided three

storytellers—English

and Theatre Studies students from The University of Warwick—with

paper copies

of folk tales,1 which were selected

on general themes such

as

family, love, and transformations, following the results of a pilot

study in

May 2012. The storytellers were instructed to perform each story as

they wished

as long as it was from memory. Each of the three schools received the

same

stories in the same order from week one to week five, which included

two

contrasting stories in week three. For consistency, the same

storyteller

returned to each school. However, when Michelle dropped out after week

three,

her school then received Alex in week four and Miriam in week five

(note that

the order of the stories remained the same, with the exception of week

three in

one school where Miriam overlooked the second contrasting story). After

the

performance, the storyteller left the room so that only the young

people and I

were present. Each group had a sheet of nine questions to initiate

group

conversation while I moved between the groups to facilitate this.

Overall, I

collected fifteen hours of focus group discussion, plus eight hours of

initial

and final interviews, which I am still in the process of transcribing

(Parfitt

2013f).

From experience

gained through

the pilot project, I expected the students to talk about emotions

during their

process of meaning-making. The focus group questions were designed to

facilitate conversation, which touched on emotions and behaviour

without

guiding them towards a specific outcome (Appendix 1). The

stories’

and

storytellers’ role was primarily aimed at creating a safe space

within the

school for conversations to occur.

The students had the

choice to

share what they wished to in the group. I informed each student in the

initial

interviews that I was interested in their opinions, and that there were

no

right or wrong responses or viewpoints. At times, I would prompt an

individual

to elaborate, but with the option to decline to do so if they wished.

As expected, there

were

differences in the storytellers’ performance styles. I hope to

illustrate this

with some extracts from the Crescent Moon Bear (Estés 1992)

performed

differently in all three schools in week two,

[Alex tells the story

in a calm

even voice throughout] out of the corner of his eye he sees this young,

scared,

dewy-eyed, young lady. Obviously his first reaction is one of

aggression, he

doesn’t know what she is doing here, why she came up this

mountain, a fight or

flight scenario. The first thing the lady does is explain about her

husband.

She explains how she needs one hair from his throat in order to save

their

marriage and home life. The bear didn’t know what to think at

first, then she

took pity on the lady (Parfitt 2013b)

[Michelle uses

physical actions,

and tone, during her performance] the woman was terrified but she did

not move

at all, the bear [raises her voice:] roared again it was so loud that

it gave

her shivers up her spine. But then she was determined to get this white

hair

from the crescent moon bear. That’s why she did not move at all.

So when the

bear pulled out his claws [raises her hands like claws] as though he

was going

to grab her—he could crush her, he could eat her—she

pleaded, [change of tone:]

please Crescent Moon Bear! (Parfitt 2013c)

[Miriam uses word

emphasis and

change of tone] It looked up, and up, until it was looking right into

the eyes

of the woman. She was so scared. Her feet were [emphasis:] rooted to

the ground

and she was trembling, she thought, I [emphasis:] can’t run away.

I need to get

the hair to help my husband. I can’t [emphasis:] run away from

this bear. The

bear looked at her and the bear [emphasis:] roared and she could see

right down

its throat it was so close. She didn’t run away. She [emphasis:]

fell to her

[emphasis:] knees [tone change:] and pleaded with the bear, please,

please

Crescent Moon Bear, please help me! (Parfitt 2013d)

These differences in

performance

style may well have some influence on the students’ process of

meaning-making.

Later analysis will involve some deconstruction of the stories relating

to

their emotional and behavioural content. This will encompass various

layers

including: the initial text provided to each storyteller, the

storytellers’

interpretation and performance of this text, and the students’

differing

interpretations.

The storytelling

sessions

occurred in two classrooms and one library. I changed these three

spaces by

moving the desks aside and pulling chairs towards where the storyteller

sat.

The aim of this was to separate the storytelling space, as far as

possible,

from the school system where work is viewed as a process of rewards.

My research is a type

of

intervention: I am creating a space

within the school where the usual rules do not apply regarding

behaviour and

emotion. These rules are replaced by those of the storytelling space.

However,

since my research was taking place within the school, I was viewed as a

figure

of authority. I exercised some authority when conducting the focus

groups, but

I discovered that the students viewed me as an outsider and were

willing to

share and discuss things that bothered them about the school in my

presence,

occasionally checking that no one from the school would hear the

recordings,

which then reassured them they were safe to do so.

These

variables—the stories, the

storytellers, focus group questions, storytelling space, individual

perspectives and interaction amongst the students, the role of the

researcher,

and wider narratives, which the students are aware of—work

together to shape

the process of meaning-making in the focus groups.

A diverse range of

fields,

including literature, anthropology, education and psychology, informed

my use

of storytelling as a methodology by demonstrating the importance of

narrative

and its potential uses. My initial interest came from SunWolf and

Frey’s work

which demonstrated that listening to fairy tales reduced anxiety in

college

students after 9/11 (2001). I then expanded my reading to include many

areas

related to storytelling and narratives, like psychology. Bettelheim

theorised,

through the deconstruction of fairy tales, that stories support

positive

psychological health outcomes by providing young people with a safe way

of

fantasying and resolving inner issues as they adapt to their social

environment

(1976: 66). His work, however, is preoccupied with a male, adult

interpretation

of fairy tales. I did not find any analysis in the interpretation of

these

stories from a young person’s perspective, which led me to

conclude that such

ideas, as well as being adult-centric, remained theoretical.

Sarbin’s work

on the narrative

analysis of life histories highlights the importance of an

individual’s

self-narratives in the formation of identity and the benefits of

narrative as a

tool to explore individual experience, because of the rich

psychological

insights it uncovers (1986). In addition, Bruner discusses how

narratives aid

individuals in constructing their reality—as inner reasoning

interacts with the

social environment. This process of meaning-making and communication is

an

important aspect of identity formation contributing to debates in

psychology

and education where interactions between school and the broader society

are

considered important in the socialisation of young people (1991; 1996;

Goodwin

2006).

To explore whether

narratives can

provide sociological insights into young people’s lives, I

decided to use

stories in the form of storytelling. In communication studies, SunWolf

has

explored Native American, Sufi, and African storytelling traditions and

their

functions: illustrating that exposure to stories benefits individuals

as a way

of learning. The influence of stories on young people and what is

learnt and

communicated through story in different ways is therefore important in

terms of

education (1999: 62). In many traditional Native American cultures, for

example, fables are conveyed in place of directly advising someone how

to act,

because it is the story and the individual’s interpretation of it

that provides

the appropriate moral and behavioural lessons held by the community

(SunWolf

1999: 51; 2004). Other research demonstrates that improvements in

education and

language ability could be linked to narrative exposure (Clark and

Rossiter,

2008; Cortazzi and Jin, 2007; Isbell et

al. 2004).

Listening to and

sharing stories

(personal or otherwise) has further potential health benefits. There is

extensive literature about the positive health effects of narratives,

including

writing therapy. SunWolf also

reflects on listening to storytelling, as well as sharing stories, in

the

context of the health care system (2005; 2008).

For the purposes of

my research,

I am interested in what conversations have been triggered by the

storytelling

space and what other narratives connected to emotion and behaviour that

the

young people refer to in their conversations. Therefore, I designed the

focus

groups to create the space to go off topic while as a facilitator I

moved

between groups giving them a degree of privacy at regular intervals. I

left the

responsibility to answer the questions to the group whilst occasionally

enquiring what they had been discussing in relation to different

questions.

That the influence of

narratives

is recognised in health care research, made me interested in whether

stories

support emotional and behavioural learning. This influenced my research

because

I wanted to use a deductive and inductive approach to see first what

narratives

young people linked to the stories, if any, and what they shared in the

groups

in terms of emotion and behaviour, which I felt would allow the

planning of

further research based on what the focus groups revealed.

The

Potential Benefits of a Storytelling Space

Although I am in the

early stages

of research, analysis of my initial findings suggests that the creation

of a

storytelling space in schools may trigger young people to share

information

about events and experiences in their personal lives. I decided to

examine what

prompted or triggered these discussions, which involved looking at the

content

of the conversations that preceded sharing.

The storytelling

performance in

week one told the story of MacCodram.

MacCodram is a Scottish story about a

group of children who are turned to seals by their step-mother. The

nature of

the curse allows them to remove their seal skins and dance on the beach

one day

a year in human form. On one of these occasions, when the children have

grown

into young men and women, a fisherman steals one of the pelts and makes

the

woman his wife. Years later his wife finds her pelt and returns to the

sea

(MacIntyre, 2013).In

the following conversation

the group had been spontaneously comparing the story they had just

heard, MacCodram, to Disney’s The

Little Mermaid when I (RES) asked

them a question,

RES

Yes, you’ve got a witch who

puts a spell on somebody. Why do you think witches are always portrayed

in that

way?

Felicity Cause

they’re witches

RES

In Snow White you’ve got an

evil step-mum

Mary

And you’ve got the witch who gives

her the apple

Heidi

People always, whenever they’ve

got a step-mum they’re always seen to be evil

Felicity My

step-mum isn’t evil! My step-dad

is but my step-mum isn’t

Mary

You have a step-dad and a

step-mum?

Felicity Well

I haven’t got a step-dad no more

[pause]. He dumped me.

(Parfitt

2013a lines.

288-296)

There are three

issues to

consider when looking at what triggered Felicity to share this

information

about her step-dad. Firstly, did the person that spoke prior to

Felicity (in

this case Mary) ask a direct question or impart information that

triggered

Felicity to share? In this instance, Felicity said ‘Well I

haven’t got a

step-dad no more [pause]. He dumped me’ in direct response to

Mary asking

Felicity a question. Therefore, Felicity’s statement could be a

result of

social interaction in response to the storytelling space that has been

created

by the research.

Secondly, I observed

which words

Felicity used prior to her comment about no longer having a step-father

to see

if her use of language might indicate a progression of thought from one

idea to

the next. The preceding comment Felicity made was ‘My step-mum

isn’t evil! My

step-dad is but my step-mum isn’t’. Felicity’s words

not only link to her

sharing statement, but are in direct response to Heidi saying that

stories

always portray step-mums as ‘evil.’ This could also be

classed as social

interaction in response to the storytelling and focus group context.

Thirdly, I considered

which words

might have led to the group discussing step-parents. Heidi, Mary, Olive

and

Felicity were talking about witches when I joined their conversation. I

listened to what they were saying and summarised that in both The Little Mermaid and MacCodram

‘you’ve got a witch who puts a

spell on somebody’. However, I then linked this to Snow

White’s step-mum

because in the story of MacCodram,

the sea-witch was also the children’s step-mother. This drew a

response from

Heidi about step-mother stereotypes and as a result Felicity shared her

experience

with her step-dad, if only briefly. Although I triggered the

conversation by

using the words ‘witch’ and ‘step-mum’, I did

this in response to what the

group was talking about, and the story of MacCodram

which they had just heard. Since the fairy tales in the study were

devised,

sociological research has shown a change in the nature of families

(Hughes

1991; Suanet et al. 2013). The

group’s conversation indicates that awareness of previous

narrative stereotypes

remains.

Looking at another

example with

the same group, I entered the conversation when the group decided they

had

finished the focus group questions. I prompted them to return to a

question,

RES

So what were you talking

about, about the characters? Did you relate to one of the characters

more than

the others?

Mary

I guess you could say the children

because we’re children, if your mum left you’d be pretty

upset. I kind of know

how they would have felt

Heidi

It’s harsh when parents split up

because then they try and make up rumours about each other and then

they try to

get the child to stay with either one or the other

(Parfitt

2013a lines.

314-319)

First, Mary relates

to the

children in the story on an emotional level ‘I kind of know how

they would have

felt’ and this prompts Heidi to share some personal experience.

Second, Heidi’s

prior comment was unrelated to the sharing conversation, she had

previously

said, ‘I think that this is probably the best group that

we’ve been put in’

(Parfitt 2013a lines.

300-301).

Third, my enquiry prompted the conversation but it is worth noting that

my

question was a rephrasing of focus group question four; what would you

do if

you were in the same situation as one of the characters? Comparable to

the

previous example sharing seems to be triggered, in the context of

storytelling

focus groups, by a combination of social interaction and the story.

Talking

about the story of MacCodram made it

possible for the girls to share personal information about their lives.

NVivo

Analysis

NVivo is a

qualitative data

analysis computer software package, which allows a deep level of

analysis on

text based research. Once I had established that a detailed analysis of

field

notes in this way might reveal the processes involved in sharing

conversations,

I used NVivo to mark all sharing conversations for the all-girls school

in

weeks one and two

(Parfitt, 2013a; 2013b).

My selection criteria sought

to identify phrases/conversations that contained personal content

around the

subject of ‘private life, relationships, and emotions’

(Stevenson, 2010).

Using NVivo, I

discovered that

the majority of ‘sharing’ conversations were preceded by me

returning to the

group to ask what they had been speaking about, or picking up on

something they

had just said and asking for someone in the group to elaborate. For

example,

when the group talked about the fisherman’s motivation for taking

the seal skin

and hiding it from his wife, I asked ‘Have there been any

situations in your

life when something like that has happened to you?’ which was a

rephrasing of

focus group question five; can you relate the plot, characters, images

or

places to your life in anyway? I found that the students shared on

eight

occasions in total over the two transcripts, six occasions followed

instances

where I asked them to elaborate, and the remaining two were preceded by

the

focus group questions. Social interaction may therefore be the trigger

in a

storytelling context rather than a list of questions or the

storytelling space

on its own. If further analysis demonstrates that social interaction

causes

people to share more, this is where real potential beneficial effects

could

come from, in terms of the storytelling space. Sharing opinions about

the story

was one of the things the students told me they enjoyed and learnt from

the

most in their final interviews. For example, Olive said, ‘It was

really good I

liked it […] it’s good cause you can listen to everyone

else’s opinion’

(Parfitt, 2013f).

Young people become

adults. How

they are integrated into, or find ways to challenge, prevailing social

rules on

behaviour and emotion is crucial to understanding how society is

reproduced or

transformed. Childhoods are fashioned in a number of diverse ways

determined by

structural components in society, such as home, education, gender,

class,

religion, and ethnicity, in addition to relationships. This has

potential

implications for policymaking since how we understand and classify

youth

governs young people’s rights, such as provision of resources,

being

acknowledged as equal citizens, as well as protective policies in

school,

medicine, and social services. It therefore determines rights and

participation

in society (Mayall 2002: 25-28, 122).

At the outset, I

proposed that

the storytelling space may trigger sharing conversations. Based on a

preliminary assessment of my data, I believe that analysing the

transcripts in

this way has the potential to show beneficial effects of the

storytelling

space, in that it may allow students to share and learn from one

another via

social interaction. This has emerged as an important part in the

process of

working towards my thesis. I will take this further by completing a

similar

analysis of the remaining fifteen hours of transcription.

In addition, it

allows students

to reflect on the influences around them in terms of behaviour and

emotion, in

a way not currently available in the school curriculum. Furthermore, it

provides insights into the conformative and subversive effects of

narrative

influences surrounding young people.

Acknowledgements

Professor Mick Carpenter and Professor Sarah Moss.

The Adam

Smith Institute.

Appendix

Focus Group Questions

Please give everyone a chance to speak. Please

give detailed

examples where possible. For example if you can link a story to your

life state

how and elaborate on it with additional information.

Q1. How would you summarise the plot in your own

words?

Q2. What images, things, or events in the story do

you like

or dislike, and why?

Q3. What other stories do you remember that you

can link to

this one?

Q4. What would you do if you were in the same

situation as

one of the characters?

Q5. Can you relate the plot, characters, images or

places to

your life in anyway?

Q6. What is this story trying to say? What do you

take from

it?

Q7. How do you feel about the story? Or how does

the story

make you feel?

Q8. What conformative/nonconformative elements are

there in

the story?

Q9. Now you’ve had experience of traditional

storytelling

how does it differ from having a story read? Do you prefer a story to

be read or

told, and

why?

Endnotes:

[1]The

fairy

tales were; ‘MacCodram and His Wife’ (MacIntyre);

‘The Crescent Moon Bear’

References:

Aesop

(1484), ‘The Horse and the Stag’ [Online]. http://www.taleswithmorals.com/the-horse-and-the-stag.htm:

TalesWithMorals.com. [Accessed 30 October

2013].

Basile, G

(1893), ‘She-Bear’, The Tale of Tales.

London: Henry and Company.

Benford,

R.D. and D.A. Snow (2000), ‘Framing Processes and Social

Movements: An Overview

and Assessment’, Annual Review of

Sociology, 26, 611-639.

Bettelheim,

B. (1976), The Uses of Enchantment: The

Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. London: Thames and Hudson.

Bruner, J.

(1991), ‘The Narrative Construction of Reality’, Critical Inquiry,18 (1), 1-21.

Bruner, J.

(1996), The Culture of Education, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

University

Press.

Clark, C.C.

and M. Rossiter (2008), ‘Narrative Learning in Adulthood’, New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 119,

61-70.

Cortazzi,

M. and L. JIN (2007), ‘Narrative Learning, EAL and Metacognitive

Development’, Early Childhood Development and Care,

177 (6-7), 645-660.

De Morgan,

M. (1987), ‘The Toy Princess’, in Zipes, J. (ed.), Victorian Fairy Tales: The Revolt of the Fairies and the Elves,

London: Methuen.

Estés, C.

P. (1992), ‘The Crescent Moon Bear’, in Women

Who Run With the Wolves: Contacting the Power of the Wild, London:

Rider.

Gabriel, Y.

(2000), Storytelling in Organizations:

Facts, Fictions, and Fantasies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goodwin, M.H.

(2006), The Hidden Life of Girls: Games

of Stance, Status, and Exclusion, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Grimm, J.

and W. Grimm (1975), ‘The Frog King or Iron Henrich’, in The Complete Grimm's Fairy Tales, London: Routledge and

Kegan Paul.

Housman, L.

(1987), ‘The Rooted Lover’, in Zipes, J. (ed.), Victorian

Fairy Tales: The Revolt of the Fairies and Elves, London:

Methuen.

Hughes, C.

(1991), Stepparents: Wicked or

Wonderful?: An In-Depth Study of Stepparenthood, Aldershot: Avebury.

Isbell, R.,

J. Sobol, L. Lindauer, and A. Lowrance (2004), ‘The Effects of

Storytelling and

Story Reading on the Oral Language Complexity and Story Comprehension

of Young

Children’, Early Childhood Education

Journal, 32 (3), 157-163.

MacIntyre,

M. (2013), ‘MacCodram and His Seal Wife’, Video Bank,

Education Scotland: http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/video/m/video_tcm4572221.asp

Mayall, B.

(2002), Towards a Sociology for

Childhood: Thinking from Children’s Lives, Maidenhead: Open

University

Press.

Moon, J.

(2010), Using Story: In Higher Education

and Professional Development, London: Routledge.

Parfitt, E.

(2013a), ‘All-girls School Transcript 1’, unpublished,

University of Warwick,

19 April 2013.

Parfitt, E.

(2013b), ‘All-girls School Transcript 2’, unpublished,

University of Warwick,

26 April 2013.

Parfitt, E.

(2013c), ‘Urban-mixed School Transcript 2’, unpublished,

University of Warwick,

2 May 2013.

Parfitt, E.

(2013d), ‘Rural-mixed School Transcript 2’, unpublished,

University of Warwick,

22 April 2013.

Parfitt, E.

(2013e), ‘All-girls School Transcript 3’, unpublished,

University of Warwick, 3

May 2013.

Parfitt, E.

(2013f), ‘Initial and Final Interviews’, , unpublished,

University of Warwick,

15 April 2013, 17 April 2013, 18 April 2013, 22 May 2013, 23 May 2013,

24 May

2013, 10 June 2013.

Pennebaker,

J.W. (2000), ‘Telling stories: The Health Benefits of

Narrative’, Literature and Medicine, 19 (1),

3-18.

Sarbin,

T.R. (1986), ‘Finding Literary Paths: The Work of Popular Life

Constructors’,

in Sarbin, T.R. (ed.), Narrative

Psychology: The Storied Nature of Human Conduct, New York: Praeger.

Stevenson,

A. (2010), Oxford Dictionary of English

(3rd edition), New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Suanet, B.,

S. Van Der Pas, and T.G. Van Tilburg (2013), ‘Who Is in the

Stepfamily? Change

in Stepparents' Family Boundaries Between 1992 and 2009’, Journal

of

Marriage & Family, 75 (5), 1070-1083

SunWolf and

L. R. Frey (2001), ‘Storytelling: The Power of Narrative

Communication and

Interpretation’, in Robinson, W.P. and H. Giles (eds), The New Handbook of Language and Social Psychology, Chichester:

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, pp.119-135.

SunWolf

(2004), ‘Once Upon a Time for the Soul: A Review of the Effects

of Storytelling

in Spiritual Traditions’, Communication

Research Trends: A Quarterly Review of Communication Research 23

(3), St.

Louis: Communication Research Trends.

SunWolf

(2005), ‘Rx Storytelling, prn: Storysharing as

Medicine’, Storytelling, Self, Society, 1 (2),

1-9.

SunWolf and

J. Lesko (2008), ‘Story was medicine: Research of The Healing

Effects of

Storytelling and Storylistening’, in Wright, K. and S. Moore

(eds), Applied Health Communication: A

Reader, Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, pp. 35-61.

Wilson, M.

(2005), Storytelling and Theatre,

London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Zipes, J.

(1979), Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical

Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales, London: Heinemann.

Zipes, J.

(1991), Fairy Tales and the Art of

Subversion: The Classical Genre for Children and the Process of

Civilization,

New York: Routledge.