Ruth

Leary, Chris

Bilton, Hannah Grainger Clemson, Nike Jung, Robert O’Toole,

Steven Ranford

Abstract:

In

November 2013 the

Institute of Advanced Studies (University of Warwick) hosted a meeting

of

interdisciplinary colleagues interested in Creative Research Methods.

The

aspirations were to kick-start the debate at Warwick and create a

platform from

which researchers can develop projects that embrace new forms of

intellectual enquiry

and knowledge production. Following the meeting, several of the

attendees

agreed to develop some of the discussion points and briefly responded

to a

number of questions in an online document over a period of a few weeks.

This

paper is the result of that real space and online collaboration.

Keywords:

creativity;

research methods; play; technology

Reflective

Discussion:

The

meeting took the form of small-group brainstorming, feeding back, and

then

continuing the discussion over some creative activities, including

origami.

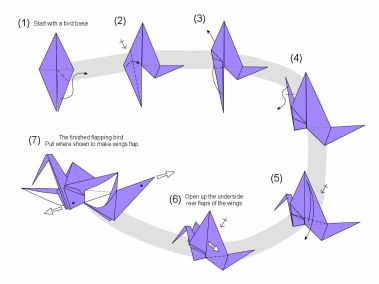

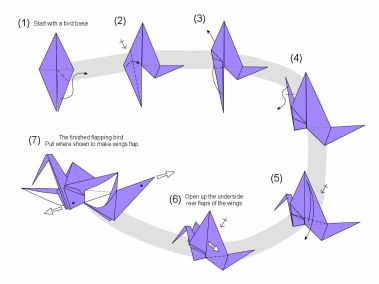

Image: Martin Jackson 2005, http://origami.island-three.net/index.html

Following

the

meeting, several of the attendees agreed to develop some of the

discussion

points. In the spirit of experimenting with alternative modes of

communication,

they briefly responded to a number of questions in an online document

over a

period of a few weeks, resulting in the following discussion. The

content and

format has been edited only in a minor way to retain the dialogic

style. The

group welcomes any comments or feedback from readers - responding

either to the

questions or the ideas.

Contributors

(in alphabetical order): CB - Chris Bilton, Director

of the Centre

for Cultural Policy Studies ; HGC - Hannah Grainger Clemson,

Research Fellow in the Institute of

Advanced Study / Centre for Educational Studies; NJ - Nike Jung, PhD

student in the Department of Film & Television; RL

- Ruth Leary, Senior

Teaching Fellow at the Centre for

Cultural Policy Studies ; RO - Robert O’Toole , Senior

Academic

Technologist & PhD student, Cultural

Policy Studies/Centre for

Education Studies/IT Services; SR - Steven Ranford, Senior

Academic Technologist for

the Faculty of Arts.

1. When

we say ‘creative’ research methods, do we mean

‘arts–based’?

HGC: I

don’t think this

is exclusively arts-based, as creative to me means trying new forms and

approaches to solve problems. I think that when working visually and

kinaesthetically

one wants to find research methods that suit and embrace that.

NJ: For

me, creative

means forgetting the rules—for a moment—to experiment and

focus more on the

process and the attempt, rather than the result, and this flow-state

can

obviously also be achieved without any art: it’s more related to

freedom from

confinement but also from immediate criticism.

CB:

Creativity is an

overused term of course, but in this context I think we’re mainly

using this as

shorthand for anything outside the normal frameworks of academic

research and

writing. Going a bit further, creativity theory stresses

bisociation—combining

different frames of reference or thinking styles in unexpected but

valuable

ways, so I think working across disciplinary boundaries comes into play

as

well.

HGC:

Isn’t this quite

dangerous, if we have not properly mastered the tools of that other

discipline? Perhaps by crossing said

boundaries, we are

also crossing out of the realm of academia as being specialist

knowledge and

skills.

CB:

Boundaries are

essential to any creative process. ‘Thinking outside the

box’ is not a helpful

term here, and expertise within a domain is still important. I’m

talking more

about combining ways of seeing and thinking, rather than

transdisciplinarity.

Bisociation could happen by combining different paradigms within an

academic

discipline, not just by importing some artistic methods from outside.

RL: I

worry about not

having properly mastered the tools of ‘that other

discipline’. If we’re talking

about a transdisciplinary approach, that’s when we should be

inviting

practitioners to work with us to develop approaches that are both

authentic (to

the discipline) and rigorous. By creative, I’m also thinking

about how we

facilitate the expression of other forms of intelligence, beyond the

linguistic

and logical, that more conventional approaches tend to favour.

2. What

has to change in order to legitimise new forms of

enquiry?

RO: We

have very few,

if any, spaces that can be ‘occupied’ by a project over a

length of time (that

is, for longer than a single session on a single day). Creative

projects

benefit from having a base that can be filled with inspiring and

challenging

materials (for example, posted on the walls and annotated with post-it

notes,

and in which prototypes and finished products may be developed,

interacted with

and tested-out. Not having such spaces significantly affects the shape

and

depth of projects. For example, when a project is hosted in its own

space, a

wider range of participants are able to access it and contribute.

Therefore, this

allows a wider range of experiences to be represented in the collection

of

inspirations/challenges, and gets more people to interact with

prototypes. By

restricting participation to time-limited slots, the possibility of

‘legitimate

peripheral participation’, with all of its direct and collateral

benefits,

becomes much less likely. For practitioners of ‘participatory

design’ and ‘design

thinking’ approaches, project spaces are essential. See for

example Brown’s

2008 paper on ‘Design Thinking’ for an account of the IDEO

3 Spaces approach.

There are also significant similarities between such project spaces and

scientific laboratories. This may help in drawing scientists into

creative collaborations,

working in spaces that are more familiar to them than the traditional

Arts

seminar.

HGC:

Does this come

down to academic snobbery and even naivety? In his book, Practice

as research in the arts: Principles, protocols, pedagogies,

resistances, Nelson (2013)

states:

Limited

attention has

been paid to the institutional constraints that in some instances have

hindered

the development of PaR [Practice as Research]. These range from strong

academic

traditions which privilege theory, to divisions between theory and

practice in

the very structures of education (university vs. art

school/conservatoire), and

regulatory frameworks which in some instances effectively exclude PaR

by

inscribing ‘the scientific method’ into research

regulations. (2013:5)

RO:

Where

participatory approaches seek to connect with and transform diverse

communities

(for example, connecting together the Arts and Sciences), project

spaces need

to be embedded and open. Bjögvinsson, Ehn, and Hilgren (2012) give

a good

account of this approach, and how they used a set of interconnected

embedded

design spaces to link together disparate communities. These approaches

are

essential when addressing complex, ill-defined, multi-perspectival,

non-linear

problems of the kind described by designers as ‘wicked

problems’ (Buchanan

1992). However! This poses a significant challenge to conventional

university

infrastructures, which are oriented towards disconnected and almost

disembodied

teaching events. My view (based on my research) is that universities

that are

able to change their orientation from the generic lecture theatre to

the

creative project space have a significant advantage. Universities that

are

locked-into the lecture/seminar/own-study triad (building ever bigger

lecture

theatres) will struggle to adapt to the requirements of a

creative-designerly

economy. Drawing upon disciplines that already work in these ways is an

essential strategy in achieving this turnaround (Theatre, Creative

Writing,

Architecture, etc.). But! Online digital spaces, when designed really,

really

well (and I’m not convinced we have anything good enough yet)

could do a

similar job.

HGC: As

a journal

editor, I am constantly encouraging authors to incorporate a range of

ways of

expressing and sharing data. Publishing online facilitates this and I

think if

the outputs shift in form, then the enquiries that lead to them will

have the

freedom to do so.

RL: I

agree there

could be a degree of academic snobbery and naivety at play here. There

is a

danger that the academy sees itself as the place of those who think,

which does

practitioners—who are equally as reflective and intellectually

engaged with

their work—a huge injustice. Collaborative working and knowledge

sharing

practices tend to place less emphasis on the role of the expert, which

means a

rethink of attitudes and priorities. We are already seeing this

reflected in

the debate about open publishing.

3. Does

the role of the researcher have to change with a more

creative methodology?

NJ: The

role of

everyone and everything involved would change - and that is scary, and

maybe

uncomfortable, because it is something new, where the rules and the

correct way

of proceeding are not yet fixed. And we are trained to avoid

‘failure’ at all

costs.

CB: I

think any

‘creative’ methodology - like creative practice - will

involve a bit more risk,

putting one’s personality on the line and the risk of appearing

ridiculous. The

approach may be more participatory too with the researcher as

orchestrator /

facilitator, rather than sole author - a surrender of authority on all

sides.

And because of the embarrassment potential, the researcher may need to

reassure

and prompt, encouraging participants to dive in without too much

forethought.

SR:

Does a pattern of starting by defining the ‘research

question’ hinder the ability for more explorative and creative

research

methods? Are there other approaches that could be explored that lead to

more

creative methodologies? Is there institutional pressure for research to

fit into

a nicely framed research question; is it a deeply ingrained habit, or

do we

need it for our brains to process and function in the research space?

HGC: So

are we

talking about barriers at an institutional level or an individual

researcher

level? In my experience there is a challenge in that the kinds of

methods we

employ often involve both a more subjective placing of the researcher

and a

re-framing as they mould evidence for dissemination. An example would

be

working with a group of participants to explore places or experiences

through

the taking of photographs or devising a performance piece.

RL: Lack

of

objectivity is a familiar criticism aimed at practice-led and other

‘creative’

research methods but subjectivity and ‘moulding the

evidence’ is an inherent

risk in all research. We are perhaps more practised at controlling for

this

within more familiar research frameworks. ‘Holding’ a space

that facilitates

both exploration and experimentation but also upholds academic values

such as

rigour and critical analysis is also a challenge. This inevitably

necessitates

a de-throning of authority but simultaneously escalates the

researcher’s

responsibility as the agent of a process which is unpredictable, and

therefore

feels riskier for all concerned.

4. How

does your interest in creative research methods

capture the spirit of your own pedagogical approach?

RL:

I’ve been

exploring my interest in this area for some time by facilitating open

space

learning workshops that draw upon kinaesthetic and experiential

learning, forum

theatre and improvisation techniques.

Storytelling, embodiment, liminality and reflective practice are

key

words for me.

HGC: Key

words that

spring to my mind are: collaboration; dialogue; narrative; playful.

CB:

Drawing an image

of organisation, role-playing a decision process or a negotiation,

playing with

Lego - these slice through the more predictable responses we might

normally

have in a classroom discussion. It’s also an opportunity for

students who may

not be so confident / articulate verbally. A mix of methods allows

different

ideas and people to come to the front. I find there’s a bit of

awkwardness /

suspicion at first but once they get going it can flow. Speed and time

limits

help!

HGC: I

agree that

there is always a degree of suspicion at first but we are in the

privileged

position of having faith in these approaches. My concerns are for a)

those

educators who have not had these experiences, and b) students (and

therefore

future researchers) coming through a primary and secondary education

system

which is in danger of losing such an ethos altogether.

5. What

do ‘play’ and ‘improvisation’ mean to you?

CB:

Starting a

sentence before you know how it’s going to…

RL: I am

reminded of

Picasso’s saying: ‘Every child is an artist. The problem is

how to remain an

artist once he grows up’. Improvisation and play mean

(re)connecting and

engaging with your inner child.

HGC:

Both have a

spirit of freedom and of trial and error, where multiple

interpretations are

expected and accepted. However, I think both are still governed by

rules,

agreed upon by the participants (even tacitly) to create purposeful

working

boundaries. There is also a sense of being the audience for each other,

rather

than a separation. This makes them quite close, personal, and

of-the-moment.

Actions can be altered ‘next time’ but the capacity for

profound and lasting

experiences is still there. The freedom to ‘play’ in

research is great, but I

am not sure ‘improvisation’ is tolerated. I’d be

genuinely surprised and

delighted to hear of examples.

NJ:

Definitely a more

interactive, less determined procedure, which involves both mind and

emotions.

HGC: At

the beginning

we discussed how ‘creative’ does not necessarily mean

‘arts-based’, however

researchers in the arts are already in tune (!) with a more messy

process of

discovery. In Research Methods in Theatre

and Performance, the editors, Baz Kershaw and Helen Nicholson,

state in the

introduction that:

Getting

lost, meeting

obstacles or generating disagreement in the methods and methodologies

maze are

intrinsic to collaboration, but these moments of confusion, dissent or

antagonism can be very research–rich (2010:2)

CB:

Getting lost also

requires a level of self-confidence. Or in the case of our students, a

trust in

the educational process and in us as educators, believing that their

confusion

is a creative journey and not merely confusing!

6. Are

we using technological tools effectively enough?

HGC: I

think there is

scope for more integration.

SR:

There is a lot of

potential to be explored in how technical tools can be integrated into

creative

research methods. In relation to both research data sources, that

people are

using to discover insight, and the ways that data is being manipulated

and

visualised. I’d argue that the techniques and mind-sets that are

needed to

effectively exploit this potential require interdisciplinary skillsets,

and are

in short supply.

RL: I

completely

agree—integration is key. I share the frustration that I have a

good sense of

the potential but lack the technical skills to realise it.

HGC: But

is it that

our generation (‘surviving school without Google’) do not

possess the skills or

is it that human superiority and belief in our own bodies and minds as

a

near-perfect window on the world

prevents us ever accepting it—perhaps

both causing a vicious circle? Is this where the arts fall down

compared

to the sciences, who have long-embraced technology?

CB:

There is a danger

of fetishising technology, especially with the emphasis on

‘digital tools’ in

education and the arts. Old technologies (storytelling, visualisation)

can

trigger new ideas.

RL: I

think we need

to be careful here. Artists have often been the first to exploit

technology in

new and unimagined ways. However, using technology gratuitously has

less value

than not using it at all; our challenge is to work out what it can add,

not

necessarily what it can substitute for. Video

didn’t kill the radio star!

7. What

do we expect or want from our research audiences?

NJ:

Ideally, to give

space and time as if it is the first time. Which goes both ways.

CB:

Ideally to be

more interested in the subject than in the method we are using to find

out

about it: open minds and curiosity from

the audiences as well as researchers, tolerance of risk and failure,

all the

things you’d hope to encounter in an audience for experimental

creative

practice.

HGC:

Less snobbery

from academics; more listening by the government; increased confidence

in the

general public.

8. What

place have emotion and lived experiences in research

methodology?

NJ: They

are in fact

in there all the time, but usually not admitted to because we still

work with a

body-mind split.

RL: I

agree. I find

this mind-body split deeply problematic and have been able to draw on

my

background in movement and dance to some extent, but there is scope for

more.

Digital storytelling and visual sociology techniques are helping us

realise the

value of emotion and lived experience and there is an emerging field of

research in memory and affect in digital media studies.

HGC:

Performance

Ethnography (see Denzin 2003 amongst others) interests me because it

directly

gets to grips with the lived experience and ‘re-lives’ it

as a way of exploring

and understanding it, but in a more objective fashion. It is an

alternative to

the singular view problem I described above.

9.

Conventional

research can be democratic. Is creativity just less

‘disciplined’?

NJ: I

don’t think

these things are mutually exclusive or opposed.

SR: I

find I’m the

most creative when responding to the challenge of enabling constraints,

rather

than in a vacuum of rules. Is creativity already the process of adding

discipline to imagination?

CB: I

agree that

there is potentially a false dichotomy here. We tend to work more

creatively

within constraints than without them. And of course one could do a lot

of the

things we’ve discussed here within the constraints of

‘conventional’ research.

HGC: If

we are being

‘creative’ then being new is perhaps going to be less

structured initially. If

we are being ‘playful’ then rules are more flexible and

boundaries are

blurred. In the other sense of

‘discipline’, the more we share of our methodologies, the

more of a CRM

‘discipline’ we can create in academia.

RL:

Maybe it’s a question of timing and

when to apply the

rules rather than a question of being less ‘disciplined’;

purposeful play as

opposed to play for play’s sake. In my experience much of the

value is realised

through structured reflection afterwards - the process alone is not

enough.

10. What

are the possibilities for creative research methods

to create higher charged, political spaces that stimulate debate?

NJ: At

this moment

that seems too early to tell.

RL: It

seems as if

the debate is gathering momentum although until now it has mainly been

the

preserve of practice-based humanities disciplines. Interest in

alternative

research methods probably needs to reach some kind of

cross-disciplinary

tipping point and I think it’s likely to be the use of new

technological tools

that will precipitate this.

Notes

The 2014

International Federation for Theatre Research World Congress will be

hosted by

the School of Theatre, Performance and Cultural Policy Studies at the

University of Warwick, 28 July-1 Aug, when the ‘Performance as

Research’

Working Group will also be meeting. For more information, visit http://iftr2014warwick.org/

Ruth

Leary is leading

an IATL funded Fellowship The Mediasmith Project exploring transmedia

documentary as a creative research method. For more information, go to http://www.warwick.ac.uk/go/mediasmith

References

Brown,

T. (2008), ‘Design Thinking’, Harvard

Business Review, June 2008, 84-95. Accessed online at http://www.ideo.com/images/uploads/thoughts/IDEO_HBR_Design_Thinking.pdf

Bjögvinsson,

E., P. Ehn, and P-A. Hillgren (2012), ‘Design Things and Design

Thinking:

Contemporary Participatory Design Challenges’, Design

Issues, 28 (3), 101-116. Accessed online at http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/DESI_a_00165

Buchanan,

R. (1992), ‘Wicked Problems in Design Thinking’, Design Issues, 8 (2), 5-21. Accessed online at http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511637

Denzin,

N.K. (2003), Performance Ethnography:

Critical Pedagogy and the Politics of Culture, London: SAGE

Kershaw,

B. and Nicholson, H (2010), Research

Methods in Theatre and Performance, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University

Press

Nelson,

R (ed) (2013), Practice as research in

the arts: Principles, protocols, pedagogies, resistances,

Basingstoke:

Palgrave Macmillan